English is a must, German is a bonus!

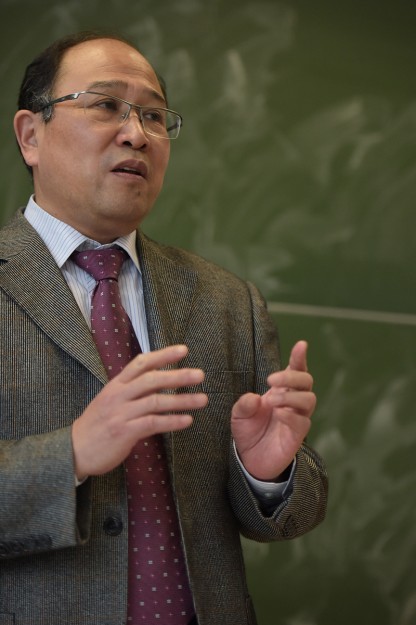

The list of his functions is impressively long and exudes internationality: President of the International Association for Germanic Studies from 2010 to 2015, Vice-Chairman of the Chinese Ministry of Education’s Advisory Committee on Foreign Language Teaching in Higher Education (Head of the ‘German in Higher Education’ working group), and President of the Shanghai Humboldt Club, to name just a few. Some people also call Prof. Zhu Jianhua the high priest of German Studies in China. He shared his thoughts on native tongues and foreign languages in academic life with Juliane Albrecht when they spoke recently during his visit to Münster University.

Why has German become so important in China and undergone such a dynamic development?

German language teaching in China has grown steadily. The reason is that, after China’s policy of reform and the opening-up of the country, importing technical know-how – in other words, scientific and technical achievements – from western countries was high on the list of priorities. And in our view Germany is the strongest country in Europe in this respect. That is what started the trend in China. Also, great names such as Goethe and Schiller, Beethoven and Mozart, Marx and Engels in the field of politics, or other philosophers, are pretty well-known in China. Today, everything is geared towards English. But the Chinese Government has registered that that is not good. Apart from English as a lingua franca, there is a need to promote other foreign languages too.

Everyone knows that you can get by everywhere with English. Does German have a high status at universities "only" as a second or third foreign language – or also as a first one? Because actually it would be better to say, "Learn English – you can’t go wrong there".

Yes, for some students that is the case, because usually they’ve already learned English at school. But here too we want to make some changes – in other words, strengthen the tendency to learn German. Many students are already learning German as their first foreign language at university. Chinese students realise that English is the lingua franca – but other cultural languages such as German, French and Japanese are also important if you want to set yourself apart from other people. So English is a must, and German is a bonus! Official government policy attaches great importance to multilingualism – after all, we live in a multipolar, multicultural world. Globalization is important not only in business, but also in culture. Since the policy of opening up the country was introduced we have had over 50,000 students in the German Faculty alone, and subsequently nearly all of our graduates had connections with Germany, to a greater or lesser extent. Many of them today hold important positions in German companies such as VW and Siemens, among others. The head of the Commerzbank in China, for example, was a graduate of ours.

Politically, Germany does not always see entirely eye-to-eye with China – I’m thinking, for example, of different values in the two countries. Do you think that German Studies – in other words, your subject – can contribute anything or improve communications between Germany and China?

I believe that cultural exchanges are very important. And there are also many misunderstandings – not only at an economic level, but also politically. What we notice in intercultural German-Chinese communication is that the two countries have different positions in world politics – but also that they have a lot in common. I believe that through courses in German Studies, as well as through exchanges – cultural or otherwise – we can build up more understanding for each other. In our German Studies courses at Chinese universities our aim is produce Chinese Germanists with intercultural competence who can communicate well in German and with Germany.

You just said that Germany and China have things in common. But picking out some of the problems again – for example, freedom of the press and personal freedom – these are certainly sticking points where the two countries do not have so much in common …

That may be true at the moment. Currently there are some problems, for example as far as freedom of the press is concerned. But I believe that exchanges of opinions – not only at government level, but also in the population at large – are very important. This is the only way to overcome problems. In China we also have a somewhat different opinion on German values, core values and the like. But here we need mutual understanding.

Have you been able to use your time here at Münster University to intensify plans for contacts or exchange programmes?

Yes, it’s something we’re planning to do. Nothing has been signed yet, but we are still engaged in an intensive exchange of ideas – with Prof. Susanne Günthner at the Department of German Studies, as well as with Martina Hofer at the International Office.

You have been occupied with German Studies for so many years now and speak excellent German. What do you love in particular about Germany or the German language?

Bochum, where I did my PhD, has almost become a second home to me. I come over to Germany almost every year. There is a lot in Germany that I find very attractive – the architecture, for example: I very much like the half-timbered houses. Tourists from abroad often go to Neuschwanstein, but I always tell people that that isn’t a typically German style of architecture. As far as the language is concerned, many people find the grammar so difficult and complicated, but it’s precisely that which I find so attractive. And I always get people to bring me German sausage. That’s what a friend in Dortmund told his delegation when they came to visit me in China. And as a result we had 20 tins of frankfurters in the house …