Worldwide collaborations – with obstacles

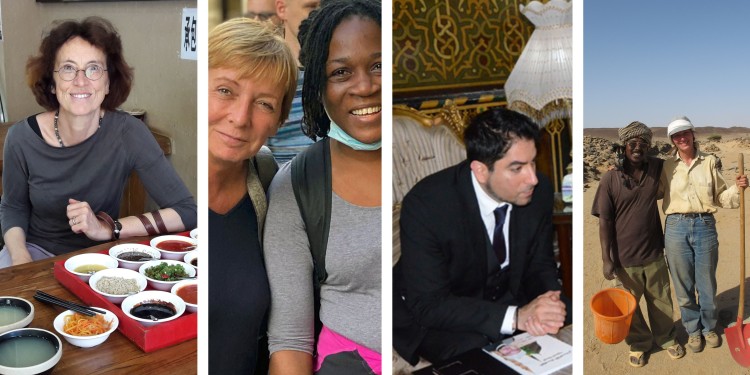

The German scholar Prof. Dr Susanne Günthner, the biologist Prof. Dr Eva Liebau, the Islamic scholar Prof. Dr Mouhanad Khorchide and the archaeologist Prof. Dr Angelika Lohwasser work with non-democratic partners. In their guest contributions, the academics from the University of Münster give an insight into their everyday work.

In addition, colleagues and PhD students from both countries collaborate on research projects, in particular in connection with Chinese-German contrastive studies. Closely linked to this research are some colloquiums and conferences held both in Xi'an and in Münster, as well as joint publications and anthologies. This cross-lingual and cross-cultural collaboration presents enormous opportunities for both sides: China is an important country specifically for German Studies, as demand for German as a foreign language has increased strongly in the past 30 years.

Of course, there are also “risks”: over the past ten years we have seen a steadily increasing politicisation of everyday life – at universities, too. In the past, there was a general consensus that openly discussing the so-called “three T-topics” – Tibet, Tiananmen and Taiwan – with students was tricky. Nowadays, however, even conferences, teaching materials and publications are “monitored” – in the Humanities, too. I very much hope that communication between German universities and China is not broken off and that, in spite of existing conflicts, we can keep up our academic and personal contacts with this fascinating country, its culture and its people.

Prof. Susanne Günthner is a member of the Department of German Studies at Münster University.

The main reason for my successful collaboration with the University of Ngaoundéré in Cameroon is a personal one: the Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Life Sciences there is Prof. Dieudonné Ndjonka, he and I were supervised by the same professor when we wrote our doctorates, and our relationship is marked by mutual esteem and trust. As a result of the many years he spent in Germany, he got to know the realities of our research work and knows what is expected – and what isn’t – when applications for external funding are made. On the other hand, he can be certain that the young researchers he sends to us at Münster will be given proper training on the equipment which is sent to Cameroon as part of our project.

For me, promoting junior researchers is the most important aspect of our collaboration with Cameroon. Almost without exception, it is the first stay abroad for them – and it will influence them. Whether in a positive or a negative way is largely my responsibility, at least as far as the scientific work is concerned. I always press for young women scientists to be sent to me because they still suffer under the yoke of male dominance – caused by financial dependence, taboos and old traditions. As a young professor I too had the experience of not being taken seriously by colleagues in Cameroon – simply because I was a woman. Scientific work in Cameroon is made more difficult as a result of events that cannot be planned for. The country has high poverty levels and ailing education and health systems, and it is characterised by corruption and various internal conflicts which endanger national security. Because of its colonial past, Cameroon is divided into two linguistic areas, French and English. As I take scientists from both areas, and the language of science is English, the French-speaking Cameroonians often have the sobering experience of seeing themselves at a disadvantage. However, I have never experienced any tension between French- and English-speaking scientists from Cameroon.

Prof. Eva Liebau is head of the Institute of Integrative Cell Biology and Physiology at Münster University.

In addition to this is the fact that Egypt – like some other Arab countries – has recently been cracking down on Islamism; people there are seeking alternative understandings of Islam outside any fundamentalist interpretations. This is why I have a big platform in Egypt for my more liberal interpretation of Islam – a platform which the state is happy to see as part of its fight against Islamism and extremism.

I admit that my academic life and my private life would be much more relaxed if I had chosen the easy option and refused to have anything to do with Egypt and other Arab countries. However, as I see my job as a kind of vocation, advocating enlightenment and peace, I see an urgent necessity not only not to abandon my colleagues there, but also to try everything to establish democratic structures step by step “from within”.

Prof. Mouhanad Khorchide heads the Centre of Islamic Theology at Münster University.

There have not been any problems so far in our collaboration, although the Antiquities Service is a government institution which reports to a Ministry – where it attracts little attention, however. Any discussion of political questions is, however, a very sensitive matter, and I can only have such discussions with close confidants. The risks involved in working in such an unstable state are self-evident: if necessary, you have to be able to react with a high degree of flexibility and, accordingly, keep your planning open. The coup which brought to an end the dictatorship of Omar al Bashir in 2019, as well as the 2021 coup which torpedoed the interim government, show the wide range of potential uncertainties. This also concerns regulations, which can change rapidly. The travel permits needed to leave the capital of Khartoum were scrapped years ago – and then suddenly reintroduced. However, no authority felt responsible for foreign guests … Ultimately, though, everything somehow works out in the end – but just not in any straightforward way. The maxim which always has to be adopted, therefore, is “patience and flexibility”!

Prof. Angelika Lohwasser heads the Institute of Egyptology and Coptology.

This article first appeared in the University newspaper wissen|leben No. 2, 29. March 2023.