On December 1, 2024, the BepiColombo mission flew past Mercury for the fifth time and, as the first spacecraft ever, observed the planet in the mid-infrared. The new data reveals differences in surface temperature and the composition of its crater-rich surface.

Mercury is the innermost and smallest of the eight planets. Outwardly, it bears a strong resemblance to Earth's Moon, but the planet differs considerably from it in terms of its structure and composition. Planetary researchers therefore still have many unanswered questions about the formation, development and structure of the planet. BepiColombo is a joint mission from the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and was launched in 2018 with the goal of answering precisely these questions. The spacecraft will enter into orbit around Mercury in November 2026. The fifth of six close Mercury flybys has now taken place, bringing the mission closer to its final orbit around the rocky planet. The MERTIS imaging spectrometer was developed and built by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) and is jointly operated with the University of Münster. MERTIS has now delivered the first detailed view of Mercury’s surface in thermal infrared, and the instrument team was particularly delighted by the vast amount of surface features visible in this first look at the surface of Mercury.

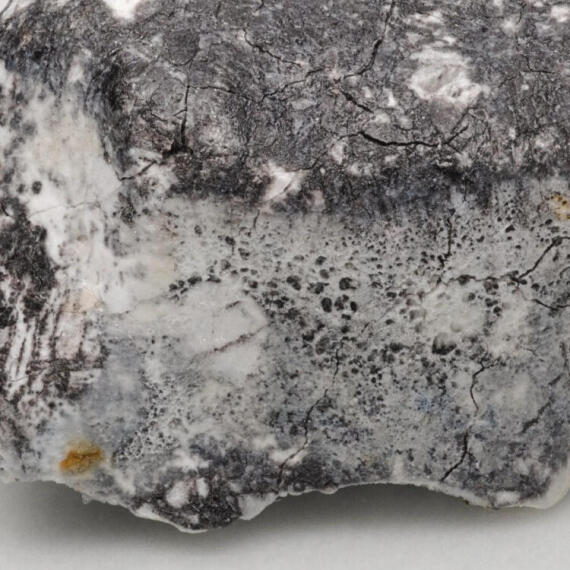

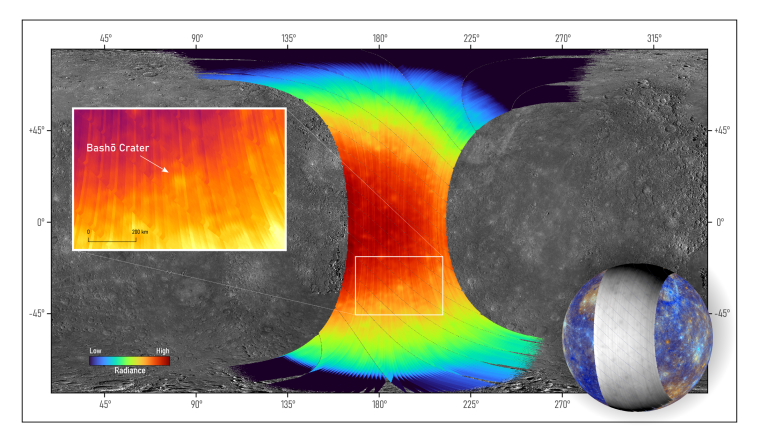

At exactly 15:23 CET on 1 December 2024, BepiColombo reached its closest point to Mercury in this fifth orbit, 37,630 kilometres above the planet's surface, resulting in a slight change in its trajectory. The flyby, or 'gravitational assist', occurred at a significantly greater distance than the previous four flybys – the previous taking place in September 2024 at an altitude of just 165 kilometres. During this latest flyby, the MERTIS spectrometer could be pointed at Mercury's surface for the first time and take measurements. Never before has Mercury been examined by a space probe in the wavelengths covered by MERTIS, from 7 to 14 micrometres. These wavelengths in the mid- to thermal-infrared range allow MERTIS (the Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer) to measure the thermal radiation of the planet's rocky crust. The MERTIS radiometer measured temperatures up to 420 degrees Celsius during the flyby. At these high temperatures, the spectral signals of minerals differ from those measured at moderate temperatures. By measuring the heat radiation, BepiColombo is carrying out pioneering work. Jörn Helbert from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research and Co-Principle Investigator for the MERTIS experiment is delighted: "After about two decades of development, laboratory measurements of hot rocks similar to those on Mercury and countless tests of the entire sequence of events for the mission duration at Mercury, the first data from the space probe is now available. It is simply fantastic!" Harald Hiesinger from the Institute of Planetology at the University of Münster leads the international MERTIS team. The planetary geologist, Hiesinger, looks to the future and adds: "It is a real pleasure to work with such a fantastic team to analyse this data. After many years of preparation, we are seeing Mercury in a completely new light thanks to MERTIS. We are breaking new ground and will be much better able to understand the composition, mineralogy and temperatures on Mercury".

"MERTIS is a unique instrument capable of providing data with a ground resolution of approximately 26 to 30 kilometres, even from this great flyby distance of nearly 40,000 kilometres, from which we can draw important insights," explains Solmaz Adeli from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research i n Berlin. As project lead, she has played a key role in planning the current flyby. Adeli adds: "From November 2026, MERTIS will be able to realise its full potential as it enters into the Mercury orbit. The Mercury Planetary Orbiter will then repeatedly approach Mercury's surface to within 460 kilometres, delivering data with a resolution of up to 500 metres."

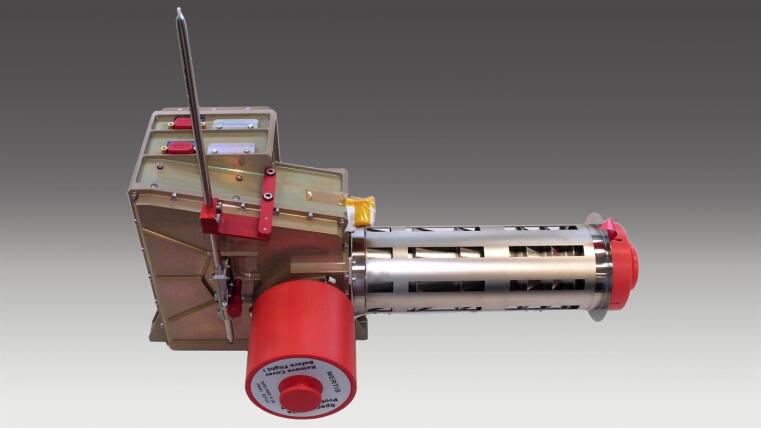

MERTIS was built at DLR with participation from German industry. The instrument design, developed by the DLR Institute of Optical Sensor Systems in Berlin, is based on a novel and highly integrated concept with a very low mass of only three kilograms and low power consumption. Gisbert Peter, the project manager responsible for instrument development at the institute, says: "After a six year cruise to Mercury, the instrument is operating very reliably and delivering impressive measurements. We are now analysing the first unique data from Mercury and, over the course of the mission, expect to obtain very high-resolution spectra from the instrument with excellent optical properties." The MERTIS team consists of numerous scientists from several European countries and the USA who are jointly analysing the data from the flyby.

BepiColombo consists of three parts that are all connected for the journey to Mercury: The 'Mercury Transfer Module' (MTM) uses its solar arrays to generate power for the ion engine and brings the entire mission to Mercury; the 'Mercury Planetary Orbiter' (MPO) is the European scientific component onboard the mission with its eleven instruments; and finally, sitting atop the MPO is the Japanese 'Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter' (MMO), inside the MMO Sunshield and Interface Structure (MOSIF) sun shield. Once at Mercury, the components will separate from each other in order to carry out their extensive scientific investigations on different orbits.