Death by ordeal: a historical topic that remains a pressing matter today

by João Figueiredo

Early morning on March 16, 2024, I received an urgent phone call from the producers of the debate show “Causa e Efeito,” broadcast by RTP África, the TV channel of the public service broadcasting organisation of Portugal dedicated to Lusophone Africa. Half guessing why they would invite a historian and anthropologist with my expertise to comment on the news, I received the confirmation that sorcery accusations, also referred to in the Anglophone world as witchcraft accusations, were again in the spotlight. Since December 2023, at least 45 people have died in the commune of Muinha, in the Angolan province of Bié, after consuming a liquid substance intended to determine the validity of sorcery accusations made against them by their peers. Last February, in Guinea-Bissau, in the wake of 37 deaths related to anti-sorcery ordeals since 2020, the Human Rights League of Guinea Bissau (HRLGB) demanded a “national plan” against sorcery accusations. Meanwhile, news reached us that in the Zambezia province of Mozambique, people with albinism keep being victimised due to sorcery beliefs.

In the aftermath of these tragic events, I discussed the topic of sorcery accusations in Africa with jurist Bubacar Turé, head of the HRLGB, and Matilde Muocha, a Mozambican medical doctor who welcomes collaborations with traditional practitioners (our panel begins shortly after minute 33, in Portuguese). As a historical anthropologist interested in legal history, my contribution to the debate was twofold. First, I very briefly situated current events in a broader historical context, countering the tendency towards presentism that often results in quick fixes being proposed to solve complex issues. Second, I highlighted that sorcery accusations, divinations, anti-sorcery ordeals, and adjudications are all interventions in the normative sphere. Therefore, they must be addressed in legal fora attentive to African societies’ cultural, legal, normative, and social pluralism. In other words, legal remedies must be imagined in addition to providing education and better healthcare to rural populations. In this post, I briefly explore the history of sorcery beliefs in Angola and the mbulungo ordeal responsible for the recent deaths in Muinha.

The longue durée of sorcery beliefs

The Italian Jesuit Priest Francisco Pacconio (1589 – 1641) arrived in Luanda, the capital of the Portuguese Captaincy of Angola, on 20 August 1623, accompanying the newly appointed Bishop of Kongo and Angola. Father Pacconio would serve in West Central Africa for almost two decades, returning to Lisbon less than a year before his death. During his stay, he wrote the first Kimbundu-Portuguese catechism, posthumously published by the Society of Jesus (1642). In its pages, Father Pacconio often struggles to convey Roman Catholic dogma to his Kimbundu-speaking interlopers, coming up with creative translations of prayers and culturally relevant ways of explaining the ten commandments, mysteries of the faith, cardinal sins, and sacraments. When discussing the eighth commandment, he clarifies:

“In this commandment, God forbids us to bear false witness against our neighbors. For example, if you say of another that he is a sorcerer, and you have seen him perform spells, but he has done no such thing” (Pacconio, 61).

Father Pacconio’s example suggests that sorcery accusations were widespread in the early years of the Portuguese Captaincy established by Paulo Dias de Novais (1510 – 1589) in 1575. Forty years after he left Angola, António de Oliveira Cadornega (1623 – 1690), a retired soldier, former ordinary judge, and council member of the senate of Luanda, wrote a three-volume chronicle of Portuguese occupation. In the pages of História Geral das Guerras Angolanas [General History of the Angolan Wars] (1680), Cadornega confirms that sorcery accusations were common, describing several divinations, oaths, and ordeals used to identify sorcerers and adjudicate sorcery accusations. A later source, the naturalist Joaquim José da Silva (c. 1755 – 1810), who also acted as ordinary judge for a while, confirmed in 1813 that for the Mbundu and neighboring nations, “nothing happened in this world that is not by the impulse of the Indelles or Sandes, who are the souls of their deceased, or by the evil deed of sorcerers” (Silva, p. 54).

Early historical accounts of the mbulungo

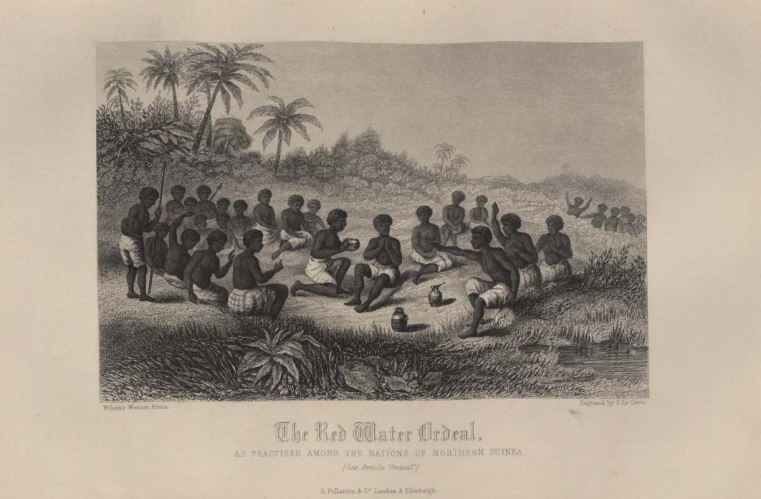

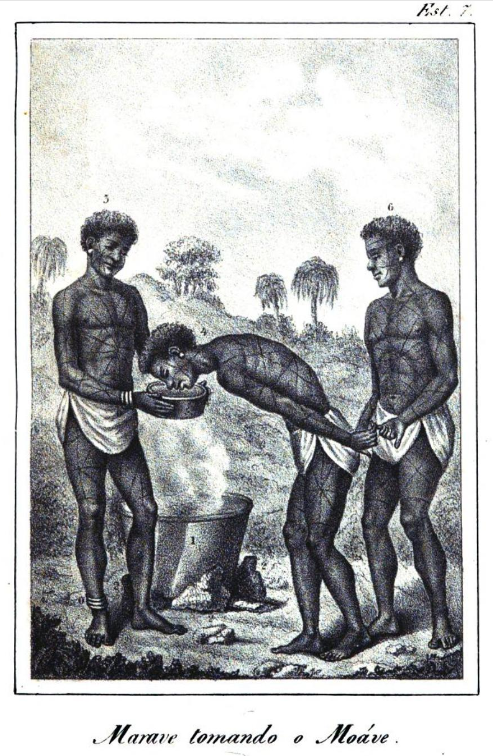

Despite being potentially lethal, an anti-sorcery ordeal was very popular among the Kimbundu-speaking Mbundu of Angola. Known as “Bulungo [mbulungo]” according to Cadornega, it was prepared in an “icao [calabash]” by mixing “hitro,” the powdered seeds of a fruit called “quijuluango,” with an alcoholic corn beverage called “oallo” (Cadornega, vol. 3, pp. 318-324). Once brewed, Cadornega explained, a ritual operator named “ganga” would gather all suspects of having committed a serious crime or misdeed such as sorcery, have them sit in a circle, and then serve them a sip of this mixture. After drinking the mbulungo, he claimed, the accused would say “bulungo me coate,” which he translates as “let Bulungo catch me,” and, if guilty, they would begin to be affected by the ordeal and either confess their guilt and receive an antidote or be left to die (Cadornega, vol. 3, pp. 318-324).

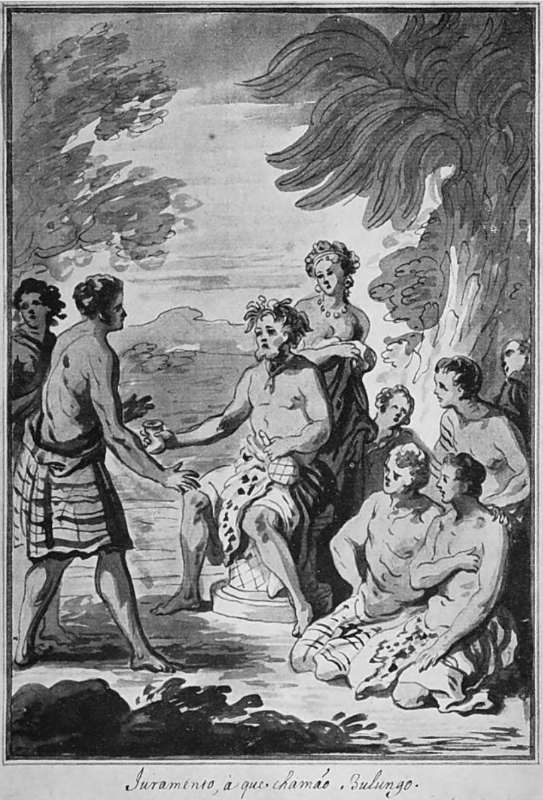

Not long after Cadornega wrote his chronicle, the Istorica Descrizione de’tre regni Congo, Matamba ed Angola [An Historical Description of Three Kingdoms: Congo, Matamba, and Angola] (1687) by Italian Capuchin Friar Giovanni Cavazzi da Montecuccolo (1621 – 1678) was published by the Propaganda Fide in Rome. In its pages, Friar Cavazzi describes the mbulungo as a “kind of oath” (Cavazzi, p. 93). In keeping with his description, it consisted of forcing the “presumed offender[s]” to drink a beverage made from several extracts, which caused them to become “alienated” and “tremble like a paralytic, unable to stand up.” Then, those offered a “countermeasure” would survive, being freed from any guilt, while the others would first become “stolid, senseless, & unable to dispose of themselves” and then “die in a few days.” According to the Capuchin Friar, “these indecent procedures of administering justice” were often manipulated by the “Judges,” who used them to “violently convict the innocent and acquit the criminals” by withdrawing the antidote and manipulating the dosages of the plant extracts employed in the brewing of the mbulungo.

Anti-sorcery ordeals are reframed as poisoning

From the period when these early accounts were collected until the effective occupation of the Angolan territory during the “Scramble for Africa” (c. 1875 – 1910), the mbulungo and several similar anti-sorcery ordeals remained common in West Central Africa. In 1881, Portuguese explorer Alexandre de Serpa Pinto (1846 – 1900) confirmed the claims of José da Silva, remarking that the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Bihe, which occupied the territory currently comprised by the Angolan province of Bié, Ovimbundu, and Mbundu alike, did not:

“…admit the existence of natural causes of disease of death. If any among them should fall ill or die, the cause is attributed either to the souls of the other world (one among the spirits being specially designated), or to some living person who has compassed the evil by sorcery or witchcraft” (Serpa Pinto, p. 130).

After performing a public ritual with the corpse to have it divine if it “was this or that living person who slew the defunct by sorcery” (Serpa Pinto, p. 130), the inhabitants of Bihe would allow the accused

“…to deny his supposed crime and to furnish a defense. He applies for such purpose to a medicine-man (by way of advocate), who, in presence of the people, proceeds to prepare his proofs, in the shape of an ordeal, to establish either the guilt or innocence of the accused. For instance, in sight of the latter’s kinsfolk and of the general public, he composes a poisonous draught, to be taken both by the accused and the nearest relative of the dead man. This draught produces a species of temporary madness, and he who suffers most from tis effects is deemed the more guilty, and has sentence of death passed upon him” (Serpa Pinto, p. 131).

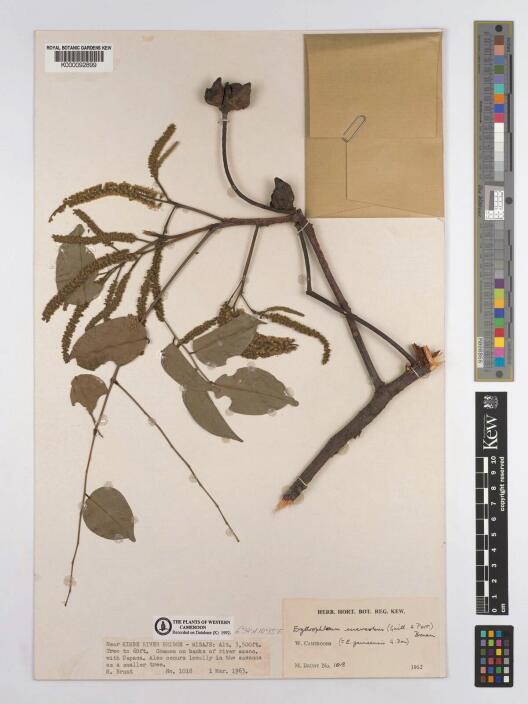

During the second half of the nineteenth century, from being interpreted as diabolical interventions, false oaths, or wasteful superstitions, ordeals such as the mbulungo went to be framed by the colonial administration as poisonings. Then, Physostigmine, one of the alkaloid substances responsible for the drastic effects of the beverage drunk during the ordeal, was identified and studied in European labs. This enabled the Portuguese to frame diverse rituals embedded in a plural constellation of African normative systems as the same underlying phenomena: a crime of poisoning, not a manifestation of legal pluralism and a way of addressing the high levels of spiritual anxiety and moral ambiguity surrounding violent or unexpected deaths.

Consequently, those who administered “poison ordeals,” organised and supervised their taking, or even knew about anti-sorcery ordeals and failed to report them to the colonial authorities were criminalised and persecuted under the Portuguese Penal Code (1886). Until independence (1975), whenever Angolan uses and customs were systematised and provisionally codified by colonial administrators, for instance in José de Oliveria Ferreira Diniz’s pioneering Populações Indígenas de Angola [Indigenous populations of Angola] (1918), a repugnancy clause would always state that anti-sorcery poison ordeals remained forbidden because they were against natural law, Portuguese sovereignty, and the police codes of civilised societies.

While the post-colonial consequences of this troubled legacy are beyond the scope of my research, a couple of years ago, I interviewed legal anthropologist Armando Marques Guedes, who confirmed that the post-colonial one-party Angolan state faced the same challenges regarding the mbulungo or similar ordeals as the Portuguese colonial administrators once had (Podcast, in Portuguese). In keeping with him, the solution of ignoring or persecuting those responsible for anti-sorcery ordeals during the 1990s resulted in them persisting underground. As the recent news from Bié confirms, the mbulungo will not disappear. The ultimate origin of evil and mishaps (what we would refer to as theodicy in theistic contexts) appears to continue to be understood in the same manner as already described by José da Silva and Serpa Pinto. Therefore, religious reforms, such as those imposed by Father Pacconio and Friar Cavazzi, or more information about poisonous alkaloids, seem insufficient to address the issue.

History suggests that legal remedies informed by legal pluralism might offer us better prospects of positive change. A forensic approach to sorcery accusations inspired by traditional forms of conflict settlement and resolution can potentially address communities’ normative anxieties in a manner that prevents escalation and is consonant with human rights approaches, offering an alternative to mbulungo. I look forward to the time when discussing its history is nothing more than an antiquarian’s futile endeavor.