Reprisal, Annexation, and Guano… oh my!

by Leslie Carr-Riegel

While perusing my research at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg I ran across a footnote mentioning a case involving the right of reprisal set before the U.S. Congress in 1857. As a medievalist studying the topic of reprisals, I felt bound to follow the lead but also a bit like Dorothy transported by whirlwind from her native Kansas to Oz. Yet, upon closer examination the tale proved so engrossing, bursting with technicolor of characters and argumentation that I felt it deserved a thorough exploration.

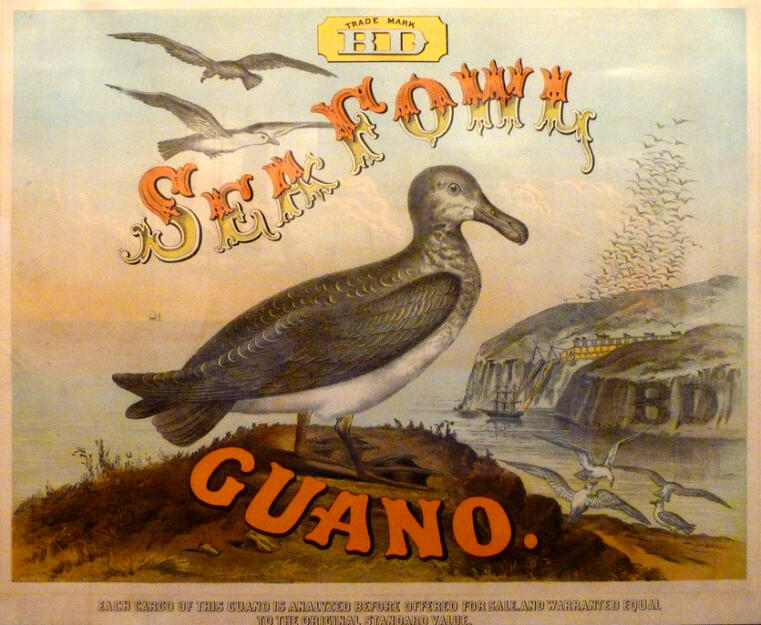

Guano – White Gold of the 19th Century

The story thus begins in the second half of the 19th century, when a gold-rush of sorts occurred on tiny islands off the coast of South America; as industrious businessmen sought to harvest a rare crop indeed – sea-bird guano. For millennia, birds had circled these isles, leaving mountain-high deposits of pooh which were valuable because their rich nitrogen content could be turned into highly valuable fertilizer and gunpowder.

The Disputed Isle of Aves

Thus, in 1854 agents of the Boston firm of Sampson & Tappan and Shelton landed on the tiny uninhabited island of Aves in the Caribbean Sea and began excavations and shipments of guano back to the United States. Five months later, disaster arrived in the form of a Venezuelan schooner and Capitan Domingo Diaz, who claimed they were violating Venezuelan soil. The United States flag was removed from its mount over the excavation site and a Venezuelan one put in its place. The twenty-five workers were then ejected by force after having signed a Spanish permisso document which, among other clauses, stated that they recognized the claims of Venezuela to the island. Upon the arrival of these men back in Boston, the uproar began.

The firm of Sampson & Tappan and Shelton were outraged that they had been kicked off the island that they had claimed as U.S. territory. They wrote, “it is not believed any government or individuals ever thought of it as a possession, and certainly none ever occupied it till last year, when we planted the stars and stripes upon it.” Venezuela had no discernable presence on the isle and, “occupation, without the animus revertendi, cannot confer anyright. Discovery must he followed by occupation” They further pointed out that the island was 600 miles off the coast of Venezuela and actually lay closer to the U.S. held territory of Puerto Rico by 300 miles. Losses for the company, between the equipment they had been forced to leave behind and future revenue denied, reached the final enormous sum of 650,000 dollars - close to 25 Million in today’s terms. What ensued was a six-year tug of war for reparations that involved parties at the highest levels of government on three continents. These proceedings produced nearly five-hundred pages of documentation, which were printed for review by the US Senate in 1861.

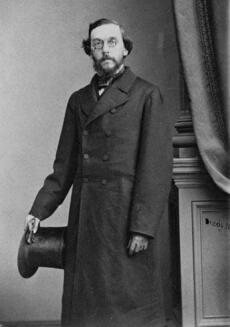

Advocate Extraordinaire - Henry Shelton Sanford

The first thing that Sampson & Tappan and Shelton did to assist with their claim, was to hire the lawyer and U.S. diplomat Henry Shelton Sanford. Scion of a prominent New England family, Sanford earned his L.L.D. at Trinity College before jumping the pond and receiving his J.U.D. in 1855 from the University of Heidelberg. His law practice was successful and he would go on to serve in diplomatic posts in St. Petersburg, Paris, and Belgium. The Aves Island case was one of his first major commissions and he took up the cause with gusto, starting a campaign of erudite persuasive letters to the U.S. Secretary of State and the President, seeking their assistance in forcing Venezuela to pay reparations and defending American honor.

Indeed, on Christmas Eve 1855, Sanford wrote to the U.S. President, describing how despite their attempts, they had received no justice from the Venezuelan authorities. “As upwards of a year has elapsed since the outrage, and as the failure of the judicial officers here to arrest the Venezuelan commander who dispossessed Mr. Shelton of his property, Captain Dias, upon a civil process, which failure was occasioned by a sudden departure from this city, every day’s delay is adding to the injury he has received.”

Holland Stakes a Claim

At this juncture, just to make things complicated, a third party stepped into the ring as the Dutch made a grab at taking possession of Aves, the rich guano isle. Holland issued an ultimatum from the deck of the lead ship of its naval squadron in January 1856. Their spokesman stated that due to the fact that Aves had once been connected to their island of San Saba by a sandbar and residents of said isle had regularly visited Aves to collect bird and turtle eggs, they were its rightful owners. Venezuela was given three days to comply. Disaster was averted when the Dutch agreed to allow a Venezuelan envoy to discuss the matter in the Hauge. The American Ambassador meanwhile, loudly protested this turn of events. The Dutch attempt at an island grab turned out to be mostly bluster however, and they eventually accepted a compromise agreement, arbitrated by Queen Isabella of Spain, to give up their claim to the island in exchange for continued fishing rights in its waters.

In April of 1856 however, with the Dutch claim still looming and the Venezuelan government maintaining a strong line that they were the rightful owners of the isle, Sanford continued his unrelenting petitioning of the US government for assistance. He wrote to the U.S. Secretary of State, “Venezuela is so utterly indigent and dishonest, (as is proved by the large amount of bonds outstanding and unpaid for years past in the hands of American citizens,) that we have little hope of obtaining pecuniary indemnity from her distinct from the restoration of the isle. We fear that the isle, and indeed we have reason to know such is the fact, has been very considerably decreased in value by the abstraction of the guano therefrom since our eviction. For this they should make compensation, and we trust it is not expecting too much for American citizens to expect that their government will exact, by coercive measures if necessary, such just compensation.”

Reprisals Might Be the Way!

It was at this point, nearly two years after the initial event and many petitions, letters, and court proceedings later, that Sanford hit on an idea which is the reason this story is of interest to us today – reprisal. Having gotten nowhere with traditional methods of pressure and persuasion Sanford wrote to the U.S. Secretary of State in July 1856 that he intended, “to solicit from Congress to grant us letters of reprisal under the law of nations, to enable us to obtain that justice Venezuela denies us.” It appears that in his legal studies, Sanford had hit upon this medieval form of dispute management and sought to resurrect it. U.S. officials appear not to have been quite sure what to make of this but were intrigued by the notion and so solicited a full brief on the topic from Sanford. What he produced, was a tour de-force 35-page treatise on the history, procedure, and applicability of the right of reprisal to the case of Aves Island.

Special Reprisals

Sanford defined his request as a “special reprisal” that would be “a national distress-warrant, and authorize the seizure and detention of the property of the citizens or subjects of the delinquent State, as well of the property of such State itself, to be brought in and detained as a pledge, and disposed of under judicial sanction, and the proceeds to be first applied to the payment of the reasonable expenses incurred thereby, and next to the satisfaction of the claim, and the surplus to be returned to the State complained of.” If enacted in the Aves Island case, this measure would enable Sampson & Tappan and Shelton by themselves or with the assistance of the U.S. Government to sequester funds and goods from private citizens and public ownings of the State of Venezuela.

Such “special reprisals”, as Sanford pointed out in his brief, had been used in Europe since the eleventh century in similar cases, and continued into the eighteenth century. He was convinced that such reprisals could serve, as they had in the past, as a means of pressuring recalcitrant foreign governments short of war. For he argued, “they are emphatically preventives of war; and because they are such preventives is it that the right to issue them should be maintained, and in proper cases enforced. Without them, if diplomatic negotiation fails to effect reparation for wrong, war is the only alternative.”

Justified by a Denial of Justice

Sanford argued that the issuing of such a reprisal would be justified in cases like that of Aves Island, where an injustice was committed by a foreign power that could not be rectified through normal means. For, “To deny justice is injustice, and unnecessary delay is equivalent to a denial. Justice is every man’s right by the jus gentium, which is therein agreeable to the natural law, as well as to the civil law and the common law; and such unreasonable delay of justice by a State to a citizen or subject of another State will, after diplomatic request and expostulation, if the case be manifest and undoubted, justify the issuance of special letters of reprisal,…” This argument was essentially the same as that put forward by the fourteenth century jurist Bartolus of Saxoferrato when he published his own treatise on reprisals in 1356 stating that, “the city or the master neglecting to do justice, or refusing to do it, is the debtor of the demands of justice, therefore the men subject to that master or the people can be sequestered.”

This still left however, the tricky issue of the taking of goods belonging to an innocent third party uninvolved in the case and related to the defendant only through nationality. Both Bartolus and Sanford defended this practice using different vocabulary but arriving at the same conclusion. Sanford grounded his arguments in the modern understanding of the citizens relationship to the State, writing defensively that, “The right to make private property the subject of special reprisals is founded upon the principle that each member of a State is bound for the liabilities of his State, and that it is not unjust to collect such liability from him, insomuch as, in such case, he has full resort to his State for indemnity, and to his fellow-citizens or subjects to make contribution.” Bartolus meanwhile, writing before the advent of the Nation State was vague in his terminology, speaking in positive terms equating the nebulous “body” to a universalized body politique, “that it is lawful for anyone to protect his body,..., of the just and right, and I mean his body, if we speak of an individual body, or of a mixed body, as of one city for him that is of his body, defending it from injuries He can grant reprisals,” for, “what one does to protect one’s body is regarded as having been done justly”. The end result of both arguments being that as a member of the group, body or state, the individual is both bound and protected by the affiliation and able to both take and be taken in reprisal.

Reprisals Covered in the U.S. Constitution and 1836 Treaty with Venezuela

Having established this foundation, Sanford moved from theoretical points of law to the positive. Here, a large difference appears between Sanford and Bartolus in that while both agreed that reprisals were governed by ius gentium- the law of nations, by his day, Sanford could also point to a number of civil laws which supported his claims. Bartolus on the other hand had been forced to admit that according to civil and canon law in his day, the practice was illegal.

The laws to which Sanford refers appear in the U.S. Constitution and in a treaty signed between the United States and Venezuela in 1836. Art. 9 Sect. 1 of the U.S. Constitution granted Congress the power “of granting letters of marque and reprisal in time of peace” - just what Sanford was requesting. Further, art. 34 sect. 3d. of the treaty between the United States and Venezuela agreed that, “If (what, indeed, cannot be expected) unfortunately any of the articles in the present Treaty shall be violated or infringed in any other way whatever, it is expressly stipulated, that neither of the contracting parties will order or authorize any act of reprisal, nor declare war against the other on complaints of injuries, or damages, until the said party considering itself offended, shall first have presented to the other, a statement of such injuries or damages, verified by competent proofs, and demanded justice, and the same shall have been either refused or unreasonably delayed.” Thus the U.S. Constitution thereby permitted special reprisals in principal; and the treaty with Venezuelan set rules regarding how such a measure should be executed, tacitly acknowledging their legality.

Executive Authority

The next question was then who could properly release a reprisal? Sanford followed medieval precedent by insisting that it was only the highest executive, in this case the President of the United States, who could issue reprisals. This, despite the fact that he admits the U.S. Constitution explicitly handed such power to Congress. Sanford argued that, “It is sufficient for us that the jus gentium, and the usages and practices of all nations under it, have provided rules and formula of procedure that save the necessity of congressional legislation to enable such rights to be maintained by the Executive.” This conclusion suited his purposes as it would vastly speed up the procedure; but he recognized that further legislation would likely be needed before such a direct method could be attempted. Bartolus and all other medieval theorists on the topic were adamant that it was only the “superioris authoritas” who could legitimately issue a reprisal.

Just Principle Cannot Die

Having presented his case, Sanford concluded by saying, “The right is founded upon the immutable principle of the law of nations, that every sovereign State possesses the right to redress its wrongs by just means, and this particular remedy has been adopted to avoid the necessity of a resort to war. A sound and just principle cannot die. It might as well be contended that because a State has long maintained peace, she lost the right to resort to war ; that such just right and remedy had become 'obsolete.'” Sanford’s brief appears to have garnered some attention. Enough that the U.S. Secretary of State wrote to his Ambassador in Venezuela intimating that a reprisal might in fact be a possibility the government would consider. However, it was not to be. Reprisals were destined to remain “obsolete” and the Aves Island case settled by other means.

The Conclusion

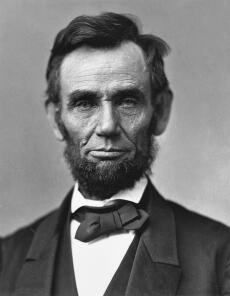

In March of 1858, a bloodless coup forced a change within the Venezuelan government, whose new leaders were desperate for recognition and friendly ties with the U.S.. They agreed to settle the case, eventually paying 105,000 dollars in damages to Sampson & Tappan and Shelton. This was agreed to by Sanford, who recognized this was the most the cash-strapped country could realistically afford. In return, the United States relinquished all claims to Aves Island. After further wrangling, payment of the agreed sum was finally completed in 1863. In his annual address to Congress in 1864, in the midst of the civil war, President Abraham Lincoln proudly mentioned the conclusion of the Aves Island affair as a glowing success under his administration.

Sanford’s brief meanwhile, after its short time in the sun, appears to have languished in obscurity. Despite the prominent diplomatic posts he took up later in life and his continued advocacy for the return of reprisals, the United States Government has yet to re-initiate the practice.

Bibliography

Bartoli a Saxaferato, Omnia Quae Exstant Opera T. 10 Consilia Quaestines Et Tractatus (Venice: 1590).

Gray, William H. “The Human Aspect of Aves Diplomacy: An Incident in the Relations between the United States and Venezuela.” The Americas 6, no. 1 (1949): 72-84.

Senate, Congress. "U.S. Congressional Serial Set No. 1082 - Senate Executive Documents, Vol. 4". Government. U.S. Government Printing Office, Doc. Nr. 10.