“In Sub-Saharan Africa, particularism supports centrifugal tendencies”

Interview with Dorothea Schulz on religious plurality in Africa

The German government has just decided to withdraw the Bundeswehr troops from Mali. France and other countries have already taken this step and ended their military deployment. From a European perspective, the country is perceived primarily as a trouble spot, with the social and (legal) historical background of the current conflict rarely making it into the media discourse.

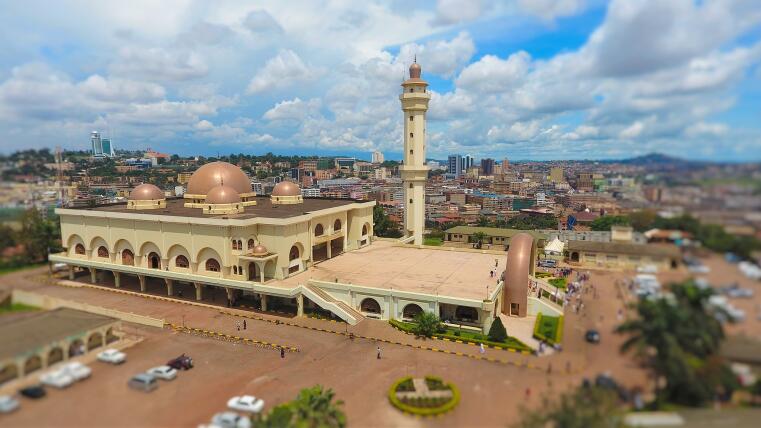

Few people over here know Mali as well as Dorothea Schulz. The anthropologist has been investigating religion and especially Islam in Africa for a long time and has completed many research stays on site. In the summer semester of 2022, she has been a Münster Fellow at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg to advance her research on religious plurality in Mali as well as in Uganda. In the process, she not only benefited herself from the cross-disciplinary discussions with her co-fellows, but also gave the Kolleg discussions important impulses on the anthropological dimensions of legal unity and pluralism. In the interview, she describes the religious constellations of Mali and Uganda and how this plurality is dealt with legally. She also discusses the resulting conflicts between the advocates of legal unity and the defenders of particular rights.

Professor Schulz, what attracted you as an anthropologist to spend a semester as a fellow at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg “Legal Unity and Plurality"? And how do you feel about the discussions held here?

First of all, I am not a legal anthropologist in the proper sense of the term. Although, I have done research in that direction since one of my specialisations has always been political anthropology and the anthropology of the state and you cannot think about those issues without applying a legal perspective. So, when the Kolleg’s directors asked me whether I was interested in working as a Münster Fellow at the Kolleg, I was really excited because I consider its thematic focus to be highly interesting. Apart from that, I like the way they set it up in an interdisciplinary way bringing together legal studies and history, which forms a complementary perspective to how matters are sometimes addressed in anthropology.

And indeed, when I joined the Kolleg, I benefited most from the debates among colleagues who argue from a historical or legal perspective. If people look from the outside at the non-European societies we study as anthropologists, they have the tendency to say “this is a different culture”. But if you look at it from a historical perspective you realise that certain aspects are not so much a matter of cultural difference but of regionally specific historical transformations, such as state-building processes, and often connected to the way a society is organised.

It is interesting that you say that, because on the other hand, historians have learned quite a lot methodologically from anthropologists in recent decades, not least the recognition of culture.

Yes, I know. My training has been at the intersection between Anthropology and History and that is when I realised that both disciplines can learn a lot from each other. Because the reverse is that historians tend to think of something as a distinct historical feature of their own society. But when they look at other contexts they can see that it is taking place in contemporary societies as well because it is connected to particular state formations.

“Those rather dramatic news about what is going on in Mali are developments of the past ten years”

You deal with modern African societies, especially those of Mali and Uganda. In Germany, we know relatively little about these countries. In the news they appear, if at all, in connection with terrorism or poverty. What fascinates you about them?

Originally, I wanted to go to Chile, then, at another time, I was learning Turkish, so I was interested in completely different world regions. Then it was pure coincidence that I came to Mali for the first time and I just loved being there. Initially, what attracted me to Malian society was that I was very interested in music and they have a very elaborate music culture there. And this particular music I was interested in has been put to political use since independence in the 1960s. So that is how I got into politics and the anthropology of the state. Now, it has been a decades-long affiliation with and love for Mali and Malian people.

Those rather dramatic news about what is going on in Mali are developments of the past ten years – whereas in the early 1990s, Mali was one of the donor darlings and model states for allegedly successful democratisation processes. So, it has not always been this imaginary place of tragedy. The reason that I am still working there right now, even despite it becoming more dangerous, is that I often have the feeling that the portrayals given in the literature and especially in the international media are so one-sided and selective. Also, there is so little understanding of the long-term historical processes that led to what is going on right now. I think we scholars bear a responsibility to give a different portrayal of Mali – and also of countries like Uganda. Of course, Uganda went through terrible times of civil strife and religiously legitimated conflicts, but that is not the whole story.

In Mali you observe a tendency towards Islamisation, which increasingly also affects state legislation. What role do Islamic legal ideas play in the slow reform of family law?

In the course of this Islamisation process, people turn to stricter understandings of “proper” Islamic worship and legal regulations. This process has been going on since the 1980s throughout Sub-Saharan Africa as well as the Middle East. In those Sub-Saharan countries, Muslims form a majority. One cannot understand this Islamisation process – I mean the fact that people who always considered themselves to be Muslims all of a sudden decide to adopt stricter applications of Islamic rules – independently of broader political and economic transformations. Partly, it is due to the influence of missionary groups who had been coming in from the Arab-speaking world in the 1980s and 1990s but since then Islamisation has become a localized process.

Political Islam is represented by a very heterogenous collection of different groups who promote a variety of understandings of strictness. But for all of them the basic goal is that Islamic regulations, rules and morals should provide the foundation of the common good.

The struggle began when Western donor organisations promoted a law reform and wanted Mali to conform its laws to international human rights conventions. There was a particular power constellation between Western-oriented intellectuals who really wanted to promote human rights standards on one side and Muslims who tried to push stricter Islamic regulations on the other. Those different Muslim groups were very effective in mobilising a broad opposition to the reform that had initially been proposed and they ultimately pushed it to the Islamic side. But it is an ongoing struggle. The gap between international human rights standards and what is laid down in the family law still exists because they could not reach an agreement.

“The divide runs within the state”

So there is a collision between Islamic law and human rights standards. What is the position of the state in all this?

That is an interesting question. I mean, that is how many activists frame it: as an opposition between proper Islamic traditions in Mali and Western cultural values as they are embodied in the universal human rights and in part in the national constitution.

But I followed these debates in the late 1990s and 2000s and you could see that the state did not respond in any homogenous way. For example, there were temporary alliances between representatives of Muslim umbrella organisations and members of the Ministry of Inner Affairs against female representatives of the Ministry of Women and Family. So the divide runs within the state.

Where does this legal reform process lead in the future?

Hard to say. At the moment, Mali is in big trouble and who knows how this situation is going to evolve. Basically, the question is really about the political future of Mali and whether the current military regime or any other government will manage to keep this country together and control all those militant groups popping up everywhere at the margins of the state. The development of the legal situation cannot be seen independently.

Besides, there has always been a big gap between what was written on paper and what was actually applied, especially with regard to family law. That was one reason why female Muslim activists put forward a certain argument about what they wanted to be regulated. Because they pointed out that rural women would no longer be protected at all by the legal changes. And in fact, those Western-oriented women’s rights activists supported a couple of legal changes that would have been beneficial to middle- and upper-class women in towns but did not address the situation of women in rural areas who have very little opportunities of legal recourse because there is little or no jurisdictional infrastructure to which they might turn.

So, I think it does not make sense to look at it just in terms of this legal reform process or of state legislation. And that of course brings us to the issue of legal pluralism or legal plurality, as I prefer to call it.

Indeed. With regard to religion, you distinguish between religious plurality as the mere fact of different religious groups in a certain area and religious pluralism as a – positive? – attitude towards it. Would you say that this distinction could also be helpful in the case of legal pluralism?

That’s a very interesting question. I don’t have a final answer but I would love to discuss it with the other fellows. In the case of religious pluralism, I make this distinction because the bulk of the literature makes a normative argument about how people should live together and practice something like religious tolerance. Whereas I think religious plurality just refers to the mere fact that there are different religious groups. Furthermore, I make the distinction of plurality between and plurality within. The former means that you have different religious traditions in one society e.g. in Uganda where you have Christians, Muslims, Jews or Bahai. Plurality within refers to settings where you have for example Muslims of completely different orientations. So, if we talk about religious plurality, we have to keep in mind that there are different dynamics of intersection.

In contrast, religious pluralism refers not only to the acknowledgement but to the acceptance of normative difference. People might say: Even if I don’t believe what you believe, it is equally valid. So, religious pluralism refers to a particular attitude, but I am not sure if this distinction holds if you talk about legal plurality and pluralism.

“The British colonial administration really laid the foundations of many of the subsequent conflicts”

You are currently investigating how religious plurality is dealt with in Uganda. What is the situation like in the country?

Uganda is a much more complicated story than Mali in terms of regional, ethnic, linguistic and religious divisions. Also, it has a much more conflict-ridden and bloodier history going back to the British colonial administration which really laid the foundations of many of the subsequent conflicts.

First of all, there is a Muslim minority but it is by no means homogeneous. The majority is Sunni, there is a Shia minority, within which you have the Isma’ilis and so on. You can even see different Muslim legal schools in the country, including two prominent ones. That has something to do with the different trajectories by which Islam entered the country. Initially, Muslims came from Sudan and they mostly practiced the Mālikī legal school. Whereas those people coming through trade routes from the Tanzanian and Kenyan coast brought their own legal traditions.

Then you also have a major division among Muslims along generational lines. This started in the 1990s with a group of young men who got scholarships to study in the Arab world. They came back with the effort of religious reforms directed against their own fathers who, in their view, did not practice a proper Islam. So, Islam itself is by no means homogenous.

Then, of course, there is the Christian majority, but here as well you have numerous different groups like Catholics, Anglicans as the predominant Protestant denomination, Evangelicals, Seventh-day Adventists, Baptists, and so on.

How is this religious plurality dealt with legally?

First of all, there is constitutional law, but it is important to look at what is actually practiced. For example, you have Sharia courts for family matters but in practice very few people go there because they are not functional. Then you have different personal status laws for different religious groups. And there is some struggle around law reform going on because some Muslim groups claim to be treated according to their Islamic law. But so far this has not really been codified. Another area of debate, similar to what is going on in Mali, is that Uganda is extremely diverse with respect to different regional customary laws and there is the question of how they interlock with Islamic norms.

In this process of standardisation and streamlining the law in conformity with international human rights standards there are various interest groups – not only Muslims – who reject it. A major conflict is always inheritance and divorce. You can easily imagine that senior men and women might have different opinions on how to regulate it. So, to reduce everything to this conflict between Muslims on one side and Western-oriented secularists on the other would be very misleading.

Would you agree with the observation that family law is particularly often affected by legal and normative plurality? If so, what are the reasons?

I think this is because the issues at stake and the challenges that need to be resolved vary from one region to another. In those postcolonial societies that became coherent countries while integrating completely different people with different cultural and legal traditions, norms and values, you have this hotchpotch of different ways of regulating contentious issues. And then of course the trouble starts – not only between but also within those groups.

Looking at these diverse societies one gets the impression that a certain degree of legal pluralism is a very fitting model. Who has an interest in standardising the law at all?

I would say only certain representatives of the state, whereas others have remained reluctant to do so. I give you an example: In Mali, the reason why inheritance, marriage and certain other areas of personal status law have never been legislated is because the local elites did not want to. They wanted to leave it open so there was more room for debate and also for manoeuvres to get a greater share of the inheritance for example. Another major issue of debate was polygamy and the question whether a husband can, at a later point, decide to turn his marriage into a polygamous one. You can imagine the dividing line between those who wanted to legislate marriage and those men who did not.

“In many countries, women’s rights activists are one interest group that is pushing this alignment between local or national legal standards and international standards”

So, is it also a question of justice and equality if the same legal rules apply to everyone?

Of course. In many countries, women’s rights activists are one interest group that is pushing this alignment between local or national legal standards and international standards. And there are others who are against it and they definitely do not all refer to Islam. There are also Christians who articulate very conservative gender ideologies. I do not want to disregard the fact that there are people who are deeply motivated by moral or religious concerns but that does not mean that there are no political or materialistic side effects that might appear desirable to them.

How to deal with different social or religious groups is also being discussed in the increasingly plural Western societies. Could the recognition of particular laws by the state contribute to a solution here?

I think, in part this is already happening. But it is certainly not a matter of whether it can be done or not, but of putting it into a broader political context. In Sub-Saharan Africa, you can see that particularism supports centrifugal tendencies. Moreover, a crucial question is who represents those communities. If you look at African settings, what you often find is that particular categories of people – more often than not older men – represent a community and define its values and norms. So, you have those internal divisions and that is why I am always a bit careful when it comes to defending any cultural heritage. I mentioned the state formation processes earlier. When I listen to the historians, what becomes clear is that there have always been alternating tendencies and trends. So, I think it is always about finding a balance between a certain degree of streamlining and bureaucratisation that is necessary to ensure a basic measure of equality, and pluralisation that leaves some room for variety in moral attitudes.

The questions were posed by Lennart Pieper.