"The plurality of norms is reflected in the language"

Interview with Claudia Lieb about the relationship between law and language

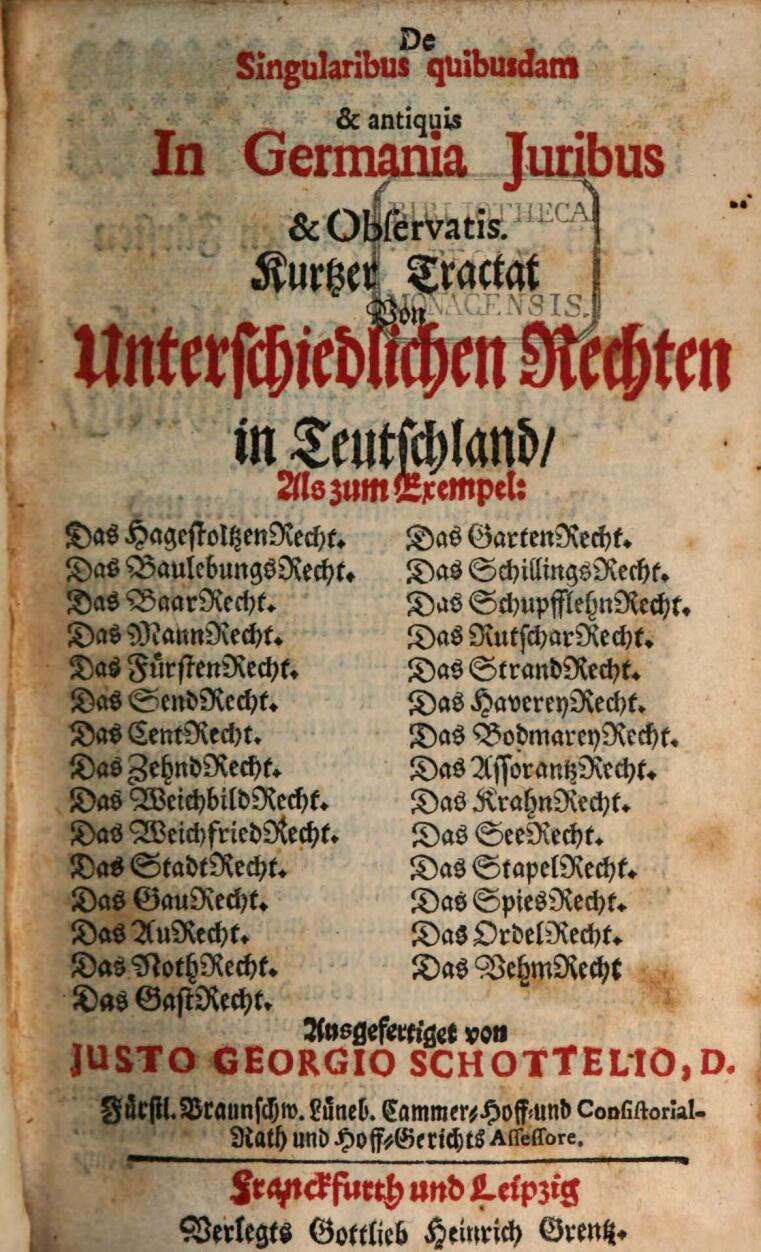

Since May 2022, PD Dr Claudia Lieb has been supporting the team of the Käte Hamburger Kolleg in looking after the local and international fellows. A scholar who has completed her postdoctoral studies (habilitation) in German studies, Lieb carries out research at the interface of literary studies and law, focusing in particular on practices of standardising legal language. Scholars such as Justus Georg Schottelius began driving this development in the 17th century, their aim being to create a uniform German legal language. But, some 150 years later, those advocating a uniform copyright law were still faced with first having to agree on common terminology. In the interview, Lieb gives an insight into her research topics and explains how closely language and law are connected.

Dr Lieb, what particularly attracted you to the position at the Kolleg?

The position is very exciting for me because it matches my interests: I have been researching in the border area between legal history, literary history, and the history of the humanities for more than ten years now. The fact that the Kolleg examines law from the perspective both of legal studies and the humanities appealed immediately to me. As I expected, the research family at the Kolleg is tremendously inspiring; and, as a literature expert, I can in turn bring in another disciplinary perspective. For example, I see in our research programme a link with poetry: since antiquity, “unity in diversity” has probably been the most well-known definition of art. It goes back to Plato’s Phaedrus, where it says that “every speech must be put together like a living creature, with a body of its own; it must be neither without head nor without legs; and it must have a middle and extremities that are fitting both to one another and to the whole work” (Plat., Phaidr., 264c1–5).

You wrote your postdoctoral thesis on the relationship between literary studies and law. As a German scholar, how come you are interested in the subject of law?

In general, I am interested in interdisciplinary relationships. That has to do with my academic background: when I studied and did my doctorate, Foucauldian discourse analysis was my method of choice and it provided information about interdisciplinary interconnections. After my doctorate, the department to which my doctoral supervisor, Detlef Kremer, belonged was dealing with “literature and law”. That’s how I came into contact with the subject of law, and it has fascinated me ever since. The basic idea of my book Germanistiken. Zur Praxis von Literatur- und Rechtswissenschaft was that Jacob Grimm could not have been the only scholar who had dealt with the interplay of literature and law. And this was in fact the case: I found out that scholars working in philology and law had already formed an intellectual community in the early modern period.

At the Kolleg, you will be dealing with language standardisation in law. What do you mean by that?

By language standardisation, I mean the process by which members of a group consciously shape and uphold their language. This can be the German language: when Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm began publishing their “German Dictionary” in 1852, they consciously wanted to standardise German. At the Kolleg, I would like to examine language standardisations to do with law – on the one hand the language of copyright law, which was formed by poets and scholars in the Sattelzeit period (1750-1850), and on the other the beginnings of legal language as a German specialist language, which I will do by using the example of the Wolfenbüttel legal scholar and linguist Justus Georg Schottelius (1612-1676).

“German was ‘in’ for language patriots like Schottelius”

Why did it seem necessary at all to legal scholars like Schottelius to switch increasingly from the 17th century onwards from Latin, the established and international language of law, to German?

German was ‘in’ for language patriots like Schottelius. The 17th century is so interesting because it was precisely then that the first steps in standardising German language were taken. During and after the Thirty Years’ War, there were patriotic reasons for revaluating German, but also eminently practical reasons: at that time, there were numerous German dialects and some written language variants, but no supra-regional German standard, scientific, legal or statutory language as we know it today. The nomenclature of learned law was Latin, but there were also particular legal sources in the German language. How in this situation could German be positioned as the language of law, so that the desire could be met linguistically to integrate law more into the German conditions prevailing in the Old Empire? Schottelius wanted to solve this problem by creating a dictionary in which he consciously shaped the German legal vocabulary.

The questions were posed by Lennart Pieper.

Typical of the epoch of the early modern period is its legal pluralism – for example, the territorial fragmentation of law or the coexistence of common law and countless particular laws. In your opinion, how far can we speak of an inner connection between the legal language, which was not uniform at the time, and the plurality or even competition of norms?

Much is still unclear here. Schottelius’ legal dictionary shows that the plurality or competition of norms is reflected in the language. This applies to legal norms that can be derived from written texts, but also to other norms, such as the language norm championed by Schottelius, according to which German tends to be cleansed of foreign words. However, he himself could not yet dispense with Latin.

You are still interested in your research in the discourses surrounding the creation of copyright law in the 18th and 19th centuries. How far are we dealing here with a process of legal standardisation?

It was initially a linguistic process: before a law could be written, the central terminology had to be clarified. The major problems at issue at the time were piracy and reprints, the common practice of plagiarism, and printing privileges that granted certain rights to the book printer but not to the author, e.g. a general printing licence or protection against reprints – and this only in a limited area. It is exciting that the texts on book reprinting, which are actually texts of legal theory, raised questions that are to do not with legal matters but with media and literary theory: What is a book? What is a work? Can a work be separated from the author? And, if so, how? At the same time, there were calls for a uniform law against reprinting books – this was difficult to implement, however, and a national copyright law did not come into force in Germany until the 20th century.

"Legal utterances have a historical and vernacular ‘sound’ or meaning that can be analysed"

The fact that language shapes reality is relatively undisputed within cultural studies. Do we need to take more account of the fact that law is also determined by the language in which it is written? And with regard to current law: How do you assess current demands for gender-sensitive language in legal and administrative texts?

Yes. The linguistic nature of law not only reflects the fact that language makes an essential contribution to the perception of the world. Those who emphasise the linguistic nature of law also emphasise the mediality of law and are suspicious of the idea that we have a simple access to reality. Earlier attempts to define law beyond its linguistic materiality as essential, substantial, organic or the like are now outdated. Instead, legal utterances have a historical and vernacular ‘sound’ or meaning that can be analysed. An example would be the metaphorical nature of the word ‘law’. Since the early modern period, there have been two metaphors in this respect in Northern Europe, these being associated with different understandings of law: on the one hand, the metaphor of law as something laid down (lag/low/law), as occurs in Anglo-Saxon, but also in Northern German; and, on the other, the metaphor of law in the sense of “the right, the proper thing”. As for gender-sensitive language: obviously, every century needs its own language standardisation. I am curious about how this attempt at standardisation, which is not limited to law and administration, will turn out, and about the corresponding dictionary of the 21st century.

The questions were posed by Lennart Pieper.