"Traders were legal actors who shaped the ancient world"

Mediterranean trade in the Roman Empire is a prime example of legal pluralism – Interview with Emilia Mataix Ferrándiz

Under what conditions did people in antiquity conduct trade with each other? How did they make agreements, how did they create mutual trust and what law did they apply? Dr Emilia Mataix Ferrándiz describes the Mediterranean in Roman times as a pluri-legal space that knew not only Roman law but also many older traditions and, in addition, countless local customs and social norms. She therefore argues for a broader view: away from state-centred approaches to the diversity of subaltern actors such as seafarers, merchants, smugglers and pirates who were all involved in maritime trade. In the interview, she explains her approach and shows how we are all affected by legal pluralism on a daily basis.

Dr Mataix Ferrándiz, you describe the Mediterranean Sea in Roman times as a site of legal plurality in which multiple state and non-state actors from various cultural backgrounds interacted with each other. Could you elaborate on that?

Thank you very much for your question. Well, when I describe the ancient Mediterranean as a site of legal plurality, I am referring to a key question in normative pluralism: the relationship between norms and practices and the distinction between different normative registers i.e. what is called “law” in a certain context and what custom or social norms. In my research, I study this phenomenon from three different angles (that are intertwined in their turn), and all coalescing into the same research focus: Roman trade.

First, we all know that the Romans conquered the Mediterranean basin and therefore established their governance in areas where other legal frameworks prevailed, such as Hellenistic, Hebrew, etc. These legal traditions did not disappear under Roman rule, but kept being used and coexisted along with Roman law. Secondly, in these different cultural and legal contexts, other sort of norms, such as customs and social uses also differed from one area to the other, and could affect some concrete areas of legal practice such as trade, which is based on a transnational and customary tradition. Last but not least, we need to bear in mind that organizing legal sources in a hierarchical system seems natural to us, but was completely alien to the Roman tradition. In that way, customs and social practices appear as influential sources that could have enormous influence on the way that people established agreements or trust among them. In that regard, it is quite important to think about the discourse of how people made their agreements valid, efficient and enforceable.

In your research project you want to bring together legal history with Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL). What are these approaches about and in what ways can they provide new insights into ancient history?

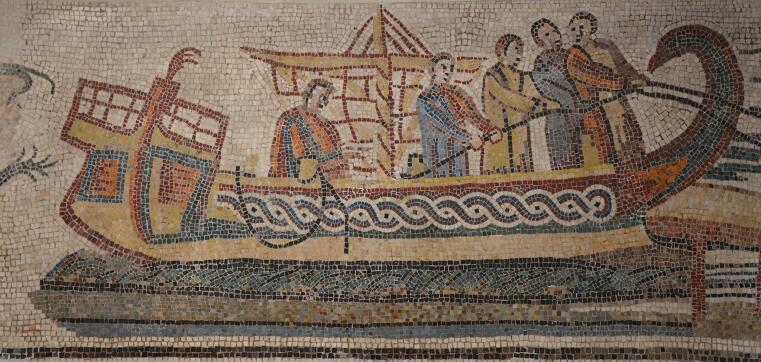

Third World Approaches to International Law is a critical school of international legal scholarship which wants to identify international law's oppressive aspects, through the re-examination of the colonial foundations of international law. When using this approach to study ancient Roman trade, my aim is twofold: on the one hand, to escape from the centre-periphery dichotomy promoted through the notions of Reichsrecht und Volksrecht promoted by scholars such as Mitteis when studying Roman law versus provincial law. These concepts denoted a strong preoccupation with unification and the model of an orderly, centralized state into whose overarching legal system those of its subjects would be incorporated, and had a long-lasting impact on how both Roman law and the Empire were viewed and conceived in nineteenth-century Europe. On the other hand, I aim to study trade in the Mediterranean as a story in which the state appears not as the sole purveyor of legitimacy but as one actor among many, in a multi-vocal and plural legal environment where a diversity of religious laws, customs and legal cultures intersected. By making this shift, we can learn a story of Roman trade and law of the sea through provincial and subaltern seafarers, traders, local authorities and pirates – not as despots, smugglers or criminals, but as legal actors who shaped the ancient world. More importantly, this perspective invites to consider the ways in which encounters in the Mediterranean Sea have not only shaped our conceptions of trade and travel but our very ideas of law, order, sovereignty, and power.

The Mediterranean world, as a site of legal plurality and multiple jurisdictions, offers alternative scales, registers, and perspectives through which to study law, legal actors, and juridical institutions. By extending the focus to the provinces and the individual actors rather than only the state or the Roman legal perspectives, I will be able to tackle issues such as identity, legal pluralities, rule of the sea, or human interaction with the physical environment, all centered on the sea as the main scenario.

Most sources from the Roman period convey a “top down perspective”. Which sources do you work with and how do you manage to identify the actions of subaltern actors?

My project looks at the law from the ground-up to ask whether, how, and to what extent Rome’s subjects availed themselves of the Roman legal system. Trade, it is assumed, is framed by legal precepts and procedures provided by the state and accepted by practitioners. The reality of trade is that merchants navigate in contexts where different sorts of legal systems, informal norms, conventions and customs coexist and mingle. Many times, these are not enforced by the authority but by social sanctions (from shunning and gossip to boycott). In addition, these transactions find validation on the will and actions of the parties involved. This way of conducting trade is especially prevalent in nearly all large premodern societies, as it is the Roman, typically struggling with weak formal institutions and lack of enforcement capabilities, relying heavily therefore on coopting and adapting imposed formal institutions to pre-existing local practices and rulings.

My research lies on the study of textual and material evidence to unravel the questions proposed. The materials emerging from trade (e.g. infrastructure, containers), as well as what merchants consider the principles governing their transactions are embedded within larger structures of human experience and meaning, and both give information about how trade operated in cross-cultural contexts. In that way, it is possible to appreciate the interactions among the different actors in trade, such as the state infrastructure controlling the traffic at ports, or the merchants inscribing their jars and indicating details of their agreements in these writings on the clay. For example, the sample of oil that I include here in a picture reflects several elements about the product, its features and modes of distribution. It tells us about how traders reached agreements and established liabilities within them. Even if written legal sources can provide context here, we need to think that in the trading world of the Romans, many agreements were not held in written but orally, and therefore trust played a big role. In these contexts, trading practices become intelligible as the commercial actors began to appreciate its usefulness, the values behind a practice, the social concepts to which it was tacitly linked, its range of uses in a given culture, its limitations, and the meanings attached to it by different groups. Only with this deeper understanding did conceptions of cross-cultural trade approach, if seldom fully reach, mutual intelligibility.

"People had their own localised conceptions about what was law"

The "mare nostrum" was the central hub of the Roman Empire. Militarily, the Romans had already pacified it during the first century BC. By what means did they try to enforce the rule of their law at sea and why did they not succeed?

This is a very tricky and complicated question. First of all, yes, supposedly the Romans had pacified the Mediterranean sea by the first century BC, especially if we think of what Augustus tells in his Res Gestae, which are a representative document of political propaganda. However, the thing is that, even if they targeted and fought piracy, this phenomenon never really disappears all along history, but peaks off or on depending on how the social and political situation is in one area. In addition, the danger of piracy changes from being performed by groups to be reduced to a local level during the Empire.

To answer more concretely to your question, I think that we need to be very careful when using terms such as rule of law applied to the Roman period. As we know, in its most basic level, rule of law implies that both the government and citizens know the law and obey it. In the Roman Empire, information was far from perfect and therefore, I doubt that many people were aware of what was the law, or they even had their own localised conceptions about what was law or what was functioning in their context (the Babatha archive from the Roman province of Judea is one key example here). In relation to that, we need to understand that certain practices such as plundering were ways by which many people of the Mediterranean have made a living for centuries and were something considered licit by their local communities, even if the Romans wanted to fight them. There is a text from Ulpian, a jurist from the third century AD compiled in Justinian’s Digest (D: 47.9.10), in which he describes how the surveillance of the provincial guards should help to prevent local fishermen from instigating wrecks, by using lights to attract ships to the shore and wreck them there. Even if the Romans wanted to keep the peace in the Mediterranean, they could not police every corner of such a big Empire (and it is even unclear that they even aimed at doing that), so in that way some old maritime customs such as this ius naufragii survived for a long time.

In a final note, we need to bear in mind that as in most ancient Empires, the tenet towards law in the Roman world was a personal and not a territorial principle, what means that Roman law was made for and used by Roman citizens. Evidently, there were ways by which Roman citizens and foreigners interacted, but bearing in mind that what counted was that personal principle, it makes it harder to establish a frame of rules that should be obeyed and known by everyone. I talk about these phenomena in my new book ‘Gone under Sea. Shipwrecks, Legal Landscapes and Mediterranean Paradigms’ that will be out soon in Brill.

In the European Middle Ages, we see cross-border trade leading to the beginnings of legal harmonisation, e.g. in the cities of Upper Italy or in the Hanseatic League. Does trade need common rules or does the Roman example show the opposite?

I think that the Roman example shows that indeed commerce was functioning because traders established diverse systems by which they enabled trust, besides from the institutional tools available during the Roman Empire. Reading the texts of the Digest, it is possible to appreciate that Roman law provided very sophisticated solutions for daily commercial issues. However, trade during the Roman Empire developed under conditions of imperfect government enforcement in private contracting. The Roman government did not have the capacity to use their policing power to coerce all private contracts made under the rules of its legal system. Thus, a big part of jurisdiction relied on non-imperial institutions, which appeared as essential for the resolution of controversies and issues. Cities provided part of this institutional protection that created trust through certified weights and measures that could vary throughout the empire. Thus, trade relies partly on abstract systems of trust, such as standardised measurements, recurrent practices, or technology; their constant use and recognisably stable features allow people to interact “as if” they trust one another. Abstract systems of trust help to make practices intelligible to people coming from different sociolegal backgrounds.

To sum up, yes, traders established some common practices to enable systems of trust, such as the use of systematic abbreviated inscriptions in containers, or practices derived from belonging to a guild, that allowed them to function and establish contact among them. Then, we are again touching the question on normative pluralism: do all these practices and trading customs count as law? Or what is considered law in a certain context?

"Material symbols were crucial elements in fostering trust among diverse cultural groups."

With your focus on the Mediterranean Sea, you also want to contribute to the question of the reception paths of Roman law. Can you already advance a theory on where we will have to rethink?

Well, I would not say that my project wants to reflect upon comparative law or reception concretely. What is true is that since trade is a very practical and customary field, and many of the risks of trading by sea do not disappear until the industrial period (and even some are still on today), my project wants to highlight certain discourses of practice to see how merchants enabled systems of legal intelligibility when navigating in diverse legally plural contexts. Using this focus of practice and intelligibility (the latter is the key concept promoted by Owensby and Ross in their book ‘Justice in a New World: Negotiating Legal Intelligibility in British, Iberian, and Indigenous America’), the phenomena studied in this project can be compared with other historical contexts involving legal pluralism (e.g. British colonies, Dutch Empire).

Especially in relation to intercultural dialogue, it is important to direct our observations away from an implicit conception of law and inquiry into the symbolic, independent and internal logic of non-state legal systems and towards processes of differentiation between various modes of norms and regulations. My project applies an actor-centered perspective, to consider the different subjects involved in trade. It explicitly considers the influence of objects on human perception highlighted in archaeology, illustrating the role of material symbols as crucial elements in fostering trust among diverse cultural groups. If technological changes on merchandise or infrastructure produce economic changes, these transitions in turn affect the legal framework governing commercial interactions. To give just one example, the Roman procedure to register goods at toll points and unload wherever the shippers wanted was quite different from Greek practice, which implied the obligation of unloading in places defined by public authorities. The latter is witnessed in some legal documents such as tax laws (e.g. customs law of Asia or monumentum ephesenum), but also in archaeological evidence from areas such as Gaul (in the area of the Narbonensis province), or Egypt (Berenike, Koptos). Thus, while these materials attest local particularities, their common significance in the context of commercial practices allowed people to interact, switch codes, or mix practices in order to obtain what they wanted in a specific transaction. The latter implies that analysing the effect of material changes with respect to legal transactions, unravels a wide range of social phenomena that can be perceived in other historical contexts, such as the impact of state power, the role of group practices, or the identity of the agents interacting with objects and infrastructures.

Before coming to Münster, you have conducted research at many universities throughout Europe. Can you think of an example where you have experienced legal pluralism in your everyday life?

We all navigate in legally plural contexts in our everyday lives, wherever we are, especially if one treats legal pluralism as a species of normative pluralism. Think of all the rules and norms I can encounter in a regular morning from my house to my office in university. After following various morning routines, such as brushing my teeth or drinking coffee, I would have walked to the office, and in that way, I would have obeyed or flouted Westphalia traffic laws, observed local driving etiquette (especially in what regards bike rules), grumbled about the university’s parking regulations, greeted colleagues and students, respected the universities’ ban on smoking and wearing a mask in the corridors as the university requires at the moment. I would have followed intricate sets of commands in checking my mail and starting my computer. I may have been worried by a circular from the central administration about some university practice, or think about how to make the library card work following their intricate set of rules concerning their cards. In drafting an e-mail message, I will have accepted or surrendered to English usages of grammar and spelling, and I may even have consulted the Oxford dictionary. And here I am not even mentioning these well-known ‘unwritten rules’ that we all experience in our profession. Academia is a key case, because many practices are mannered and also some forms of interaction are tied to concrete contexts. Following these unwritten rules will affect the way that one is perceived in the academic circle and therefore, if subjects from higher rank consider that this person respects hierarchies and can be then trusted. That goes from how to write an email to the way one handles social interactions or addresses professors who are up in the hierarchy. In sum, we all encounter normative pluralism every day. It is hard to deny it as a social fact.

The questions were posed by Lennart Pieper.