Pluralism of what? On Laws, and on Rights – in Translation

by Gregor Albers

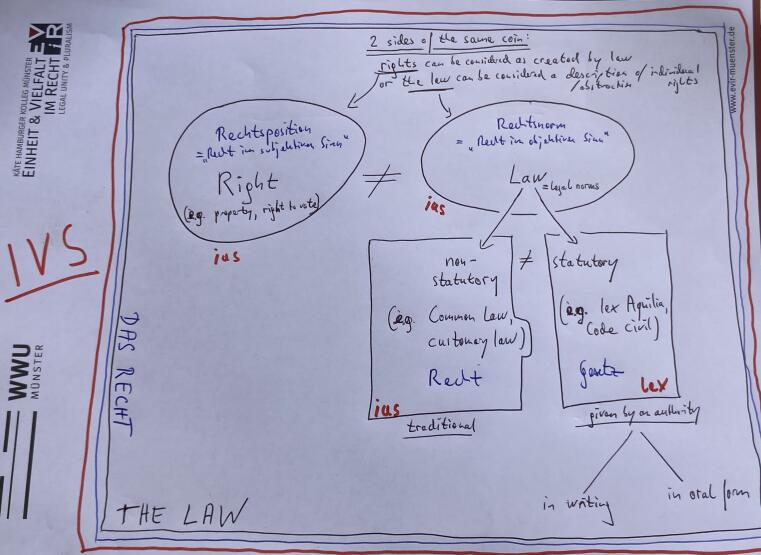

European legal terminology is often organised in dichotomies. In the continental languages, this holds true for the concept of law itself, which can be ius or lex, droit or loi, diritto or legge, Recht or Gesetz. These dichotomies cannot easily be translated into English.

The problem does not lie with lex / loi / legge / Gesetz. These expressions refer to laws enacted by some authority, usually as the result of a formalised process. Nowadays, we tend to imagine them as written down, but this is not essential: The tradition of legislation relies strongly on popular assemblies and their oral deliberations and decisions. The Latin lex can also refer to a provision of a contract (lex privata), but this is not a point I wish to stress here.

The main difficulty lies in the variety of meanings of ius / droit / diritto / Recht:

(1) ius / droit / diritto / Recht can be used as a general term to describe anything legal, very much like the English “law”.

(2) ius / droit / diritto / Recht can describe a subcategory of “law”, namely non-statutory or traditional law (like the Common law) as opposed to statutory law given by some authority (lex / loi / legge / Gesetz).

(3) ius / droit / diritto / Recht can mean the same as the English word “right”, examples being your property, my right to vote, a claim for damages, a right not to be discriminated and to enjoy equal opportunities.

I tried to put that into a picture:

Reflection on these terms might have some impact on the debate on legal pluralism, a debate which has been shaped very much by the English language.

First, if someone is looking for non-state law or law beyond the state, they might already be satisfied if they find ius / droit / diritto / Recht in the sense of norms not given by some authority but handed down from the past (meaning (2), see above).

Second, it might be useful to talk a bit more about rights. Oftentimes, people will not care about the law, but about their rights. Under “ideal” circumstances, this should amount to the same. Rights and legal norms can be considered two sides of the same coin. It is a matter of debate which side comes first – are rights created by legal norms, or are legal norms phrased to describe the effects of individual rights? But they should belong together. Still, change might affect them differently. There are many ways to come under the influence of some new law – maybe they invaded my home, or there was a revolution, or maybe I just travel and find myself brought before some alien court. This new law, even if it pretends to have precedence over the set of rules I submit to, might have a certain respect for rights I have acquired under my old law (iura quaesita). This continuity of individual rights might take the edge off some collisions between legal orders. By contrast, conflicts are going to be harshest whenever the difference between legal orders is mirrored by competing individual claims (e.g. different parties claim property in land on the basis of different sets of norms).

Many problems remain: The scheme presented does not seem to adapt easily to collective rights. Moreover, the practical and procedural side remains in the shadow (a law in the sense of a system of norms tends to come with its own set of courts and procedures, but there might also be a right to be tried by one’s own courts). I would be happy to see the picture enhanced and corrected. I cannot begin to imagine how problems of terminology multiply once one leaves the narrow limits of Western Europe.

Further Reading

Gregor Albers: Norm, rechtlich (Rechtsnorm), in: Münster Glossary on Legal Unity and Pluralism, 2nd edition (EViR Working Paper 05), Münster 2023, pp. 69-73, DOI: 10.17879/90089657999.

Gregor Albers: Recht (Rechtsposition), in: Münster Glossary on Legal Unity and Pluralism, 3nd edition (EViR Working Paper 06) [forthcoming].