Background

"The border environment is diverse. Mountains, deserts, lakes, rivers and valleys form natural barriers to passage. Temperatures ranging from sub-zero along the northern border to the searing heat of the southern border effect illegal entry traffic as well as enforcement efforts.

Illegal entrants crossing through remote, uninhabited expanses of land and sea along the border can find themselves in mortal danger."

- Border Patrol Strategic Plan 1994 and Beyond: National Strategy

Hostile Terrain 94 and the US-Mexico Border Regime

“Hostile terrain” is the term used by the US Border Patrol to describe the “remote, uninhabited expanses of land and sea along the border” which separate Mexico from the United State and encompass stretches of the Sonoran Desert. The 1994 Border Patrol Strategic Plan uses this hostile terrain as a natural and potentially deadly deterrent to migrants. Directed at preventing illegalized immigration into the US, the strategy “prevention through deterrence” foreclosed relatively safe pathways across the border near major urban entry ports. Intensified use of surveillance technology and an increase of border patrol agents were some of the measures taken to close off those entry ports and to raise the risk of apprehension for illegalized migrants.

This only leaves undocumented migrants with alternative routes into the US – the hazardous journey through the hostile terrain of the Sonoran Desert. The enormous difficulties and (often mortal) dangers posed by this route are willingly accepted by Border Patrol in the hope that these would eventually discourage people from attempting the crossing in the first place.

This strategy not only puts migrants deliberately at risk, but also chooses not to take responsibility for the root causes for migration into the US. Migrants would not risk their lives trekking through the desert if they saw any hope for a safe and happy future in their home countries, which are oftentimes those South and Central American countries where US interventionist foreign policy has shown total disregard for democratic structures and human rights since the 1960s.

For many migrants, the journey through the Borderlands is driven by the pure will to survive and to escape from poverty, violence, or persecution; and so they continue to attempt traversing the Sonoran Desert as a last resort. “Prevention through deterrence” does not prevent undocumented migration but constitutes yet another US policy marked by contempt for certain people’s lives and human rights. Since 2000, more than six million people have attempted to cross the Borderlands, often with tragic consequences. At least 3,200 undocumented migrants have died on their journey north, largely from dehydration and hyperthermia. Despite its calculated failure, “prevention through deterrence” continues to be the major enforcement strategy at the U.S.-Mexico border.

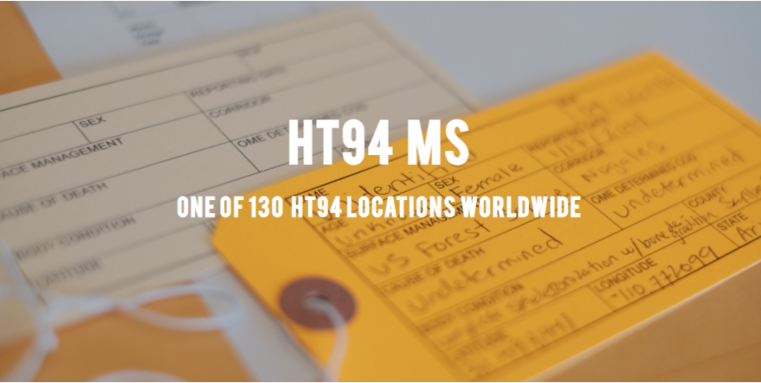

The global participative art exhibition project “Hostile Terrain 94” seeks to draw attention to the fatal consequences of this border enforcement strategy and to the many victims it has claimed. Its centerpiece is an installation composed of 3,200 toe tags that volunteers fill in by hand before they are mounted on a wall map of the Borderlands. Each toe tag contains those details about a deceased individual that could be gathered from their remains in the desert. While the information made visible on the tags places the border crosser in the bureaucracy of the state apparatus, the process of filling out toe tags is a community-based practice of witnessing and commemorating the silenced dying happening in the desert. Once the toe tags have been filled out, volunteers map the Borderlands as a haunted space by pinning each tag to a wall map of the US-Mexican border in the exact spot where the remains of a migrant were found.

The project was initiated by the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), a non-profit research-art-education-media collective based at University of California, Los Angeles, and directed by anthropologist Professor Jason de León. Between 2020 and 2021, over 130 organizations and institutions around the world are hosting the project in their communities, seeking to spark a public debate about migration, border politics, and collective remembrance. In Münster, the project is organized at the University by the English Department in cooperation with the Kulturbüro.