On the way to Mercury: spacecraft "BepiColombo" flies towards Earth

In the early hours of 10 April, the European Space Agency (ESA) BepiColombo spacecraft will fly towards Earth at over 30 kilometres per second. At 06:25 CEST it will make its closest approach, over the South Atlantic, at an altitude of 12,677 kilometres. The spacecraft will then fly further towards the centre of the Solar System, travelling somewhat more slowly than when it arrived. The main purpose of the so-called Earth flyby is to slow down BepiColombo somewhat without expending propellant, in order to bring the spacecraft onto a trajectory towards Venus.With two subsequent close flybys of Venus (the first flyby will take place on 16 October 2020), BepiColombo will then be on a trajectory that will take it to the destination of the six-year journey, an orbit around Mercury, the innermost planet of the Solar System.

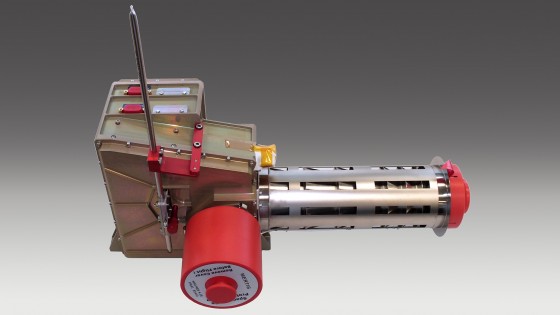

For planetary researchers at the Institute for Planetology at the University of Münster and theGerman Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) this is a unique opportunity to conduct a unique experiment, where they will study the Moon. As early as 9 April, with its Earth-facing side illuminated by the Sun, the Moon will be observed for the first time in the thermal infrared and examined for its mineralogical composition using the Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (MERTIS) instrument. This will be possible because there will be no absorption by Earth’s atmosphere. At Mercury, MERTIS will investigate the composition and mineralogy of Mercury’s surface and investigate the planet’s interior.

During its flight towards Earth, on its spiral orbit through the inner Solar System, it will travel at a speed of 30.4 kilometres per second. As it moves away from Earth, BepiColombo be travelling at a speed of approximately 25 kilometres per second. Due to the enormous gravitational field of the Sun and the limited transport capacity of the available launchers, planetary missions to the inner and outer Solar System can only be accomplished by following very complex trajectories.

“The Moon and Mercury are not dissimilar in size, and their surfaces resemble one another in many ways,” explains Harald Hiesinger from the University of Münster, Principal Investigator for the MERTIS experiment. After decades of lunar research, he is particularly looking forward to the new measurements. “We will obtain new information on rock-forming minerals and the temperatures on the lunar surface and will later be able to compare the results with those acquired at Mercury. The Moon and Mercury are two important bodies that are fundamental to enhancing our understanding of the Solar System,” Hiesinger adds: “I am anticipating many exciting results from the observations with MERTIS. After about 20 years of intensive preparations, the time will finally come on Thursday – our long wait will be over, and we will receive our first scientific data from space.”

The scientific evaluation of the data will then be carried out jointly at participating institutes in Münster, Berlin, Göttingen and Dortmund, as well as several locations in Europe and the USA.

Last chance to see ‘Bepi’ – but not in Germany

Space enthusiasts are, of course, interested in knowing whether they will have the opportunity to see BepiColombo one last time, during the flyby, before it leaves on its way to the inner Solar System. The answer is indeed yes. However, this will only be possible south of 30 degrees north over the Atlantic, in South America, Mexico and, with some restrictions, over Texas and California. In Central Europe, the consolation remains that on the night of 7 to 8 April, there will be an exceptionally large full Moon, commonly referred to as a ‘supermoon’.

Background information:

MERTIS has two uncooled radiation sensors. Its spectrometer is sensitive to wavelengths of between seven and 14 micrometres, and its radiometer to wavelengths of between seven and 40 micrometres. It will identify rock-forming minerals in the mid-infrared at a spatial resolution of 500 metres.

“We will not be able to obtain such a detailed resolution when observing the Moon,” explains Gisbert Peter, MERTIS Project Manager at the DLR Institute of Optical Sensor Systems, which was responsible for the design and construction of MERTIS. Having the Moon in the spectrometer’s field of view before the flyby is partly an astronomical or geometric “coincidence” and, above all, due to good planning. MERTIS will observe the Moon from distances of between 740,000 and 680,000 kilometres for four hours. Here, the instrument, which is very compact at 3.3 kilograms, will be able to demonstrate its unique optical properties for the first time in orbit. Three small cameras on the exterior of the BepiColombo spacecraft will also acquire images of Earth during the approach.

Third mission to Mercury

While MPO is designed to analyse the planetary surface and composition, MMO will explore its magnetosphere. Further goals of the mission are the investigation of the solar wind, the internal structure and the planetary environment of Mercury, and its interaction with the near-solar environment. Scientists also hope to gain insights into the formation of the Solar System, and Earth-like planets in particular. Until they reach Mercury orbit, the two spacecraft will travel as part of the Mercury Composite Spacecraft (MCS). This includes the Mercury Transfer Module (MTM), which supplies the orbiters with power and protects them from the extreme temperatures as they approach and fly past Mercury. MCS is also equipped with the Magnetospheric Orbiter Sunshield and Interface Structure (MOSIF), which will further protect the MMO before it enters orbit. Surface temperatures on Mercury range between 430 degrees Celsius on the day side and minus 180 degrees Celsius on the night side. On 5 December 2025, after six flybys of Mercury, the MPO, MMO and MOSIF will enter an initial capture orbit.

Juggling gravity and velocity

Flyby manoeuvres, also referred to as ‘Gravity Assist Manoeuvres’, have become routine for space missions. They are used to change the flight trajectory and speed of spacecraft without using propellant, by employing the gravitational fields of planets. Leaving Earth’s gravitational field and reaching a distant destination in the Solar System requires a great deal of energy for acceleration, for changes of direction, and also for deceleration at the destination. Carrying this energy in the form of propellants for engines or thrusters is expensive in terms of mass and would inevitably reduce the payload that can be carried or simply make the mission technically unfeasible.

Close flybys of planets enable an elegant technical solution. If a spacecraft approaches a planet, that planet’s gravitational attraction prevails over that of the Sun at a certain distance, influencing its movement. In a sense, a flyby is the juggling of two forms of energy – the kinetic energy of the spacecraft and the planet’s potential energy, which, with its much greater mass, attracts the small spacecraft during its approach. With this juggling, depending on the spacecraft’s velocity and proximity to the planet, energy can be transferred from the planet to the spacecraft, or vice versa. The visitor then either begins to travel faster (and the planet slows down imperceptibly) or, with kinetic energy being transferred from the spacecraft to the planet, the craft slows down (and imperceptibly accelerates the planet in return). The speed of the spacecraft does not change in relation to the planet; its overall velocity and trajectory are only modified. However, since the planet is in orbit around the Sun, this change in the trajectory of the spacecraft causes it (and minimally the planet) to accelerate or slow down on their orbits around the Sun.

The ingenious trajectory solution proposed by Giuseppe ‘Bepi’ Colombo

For the first time, flyby manoeuvres along a planetary orbit were used on the Mariner 10 mission to allow two more close flybys after the first flyby of the planet Mercury. The calculations were made by the Italian engineer and mathematician Giuseppe ‘Bepi’ Colombo. In 1970, Colombo, a professor at the university in his hometown of Padua, was invited to a conference at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, held in preparation for the Mariner 10 mission. There, he saw the original mission plan and realised that, with a highly precise first flyby, two more close flybys of Mercury were possible. The current European-Japanese mission to Mercury was named in his honour.

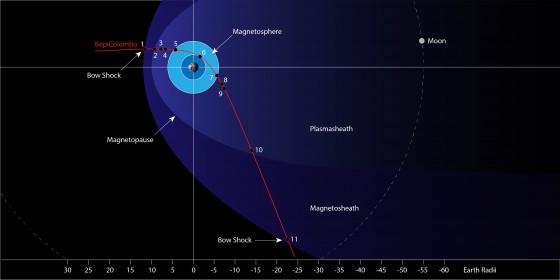

Of the 15 instruments on board the two orbiters, three were largely developed in Germany: BELA (BepiColombo Laser Altimeter), MPO-MAG (MPO Magnetometer) and MERTIS. The DLR laser experiment BELA will only be operated when the spacecraft reaches its destination. The magnetometer is already being used to carry out measurements during the flight through Earth's magnetosphere, which extends far into space. Funded by the DLR Space Administration, it was developed and built at the Institute for Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics at TU Braunschweig in collaboration with the Graz Space Research Institute and Imperial College London.

Close European-Japanese cooperation

Overall management of the mission lies with ESA, which was also responsible for the development and construction of MPO. MMO was contributed by JAXA. The German contribution to BepiColombo is coordinated and mainly financed by the DLR Space Administration, with funds from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). The two instruments BELA and MERTIS, which were mainly developed by the DLR Institutes of Planetary Research and Optical Sensor Systems in Berlin-Adlershof, were largely financed from DLR’s Research and Technology budget. The mission is also being supported by the Westfälische Wilhelms University of Münster, TU Braunschweig and the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Göttingen. A European industrial consortium led by Airbus Defence and Space designed and constructed the spacecraft.