Notes on the Portrait

of Nikias of Cos*

Zusammenfassung: In den ausgehenden

40er und 30er Jahren v. Chr. beherrschte der Tyrann Nikias von

Kos seine Heimatinsel. Während seiner Herrschaft, deren Dauer

sich nicht exakt rekonstruieren lässt, prägte er Münzen mit

seinem Porträt. Im vorliegenden Beitrag wird argumentiert, dass

die Bildnisse, die entgegen gängiger Forschungsmeinungen weder

das Diadem der hellenistischen Könige noch einen Lorbeerkranz

tragen, sich aus politischen Gründen an denen Marc Antons

orientierten.

Schlagworte: Nikias von Kos (d-nb.info/gnd/102400474),

Bildnis (d-nb.info/gnd/4006627-7),

Marcus Antonius (d-nb.info/gnd/118503529),

Kos (d-nb.info/gnd/4829027-0),

Münzbildnis (d-nb.info/gnd/4308642-1)

Abstract:

In the late 40s and 30s BC the tyrant Nikias of Cos reigned his

homeland. During his reign, which cannot be dated with absolute

certainty, he minted coins with his portrait. This paper argues

that these portraits, neither adorned with a royal diadem nor

with a laurel wreath contrary to former research, were modelled

after those of Marc Antony.

Nikias of Cos is a

figure from the ancient world about whom we are not very well

informed. Despite the facts that he was tyrant of Cos

approximately around the years 40–30 BC and that in this

capacity he minted bronze coins with his portrait on the

obverse, his vita has to be reconstructed with much effort from

scarce hints in literary sources and a very broad but uniform

epigraphic record[1].

This paper will accordingly not rewrite the history of Nikias,

but focus on an analysis of his coin portrait. After a brief

historical introduction, the coinage of the tyrant and the

questions connected with it will be briefly presented. The main

goal of this article is to analyse the portraits on the obverses

of these coins in depth for the first time and discuss them

against the background of relevant contemporary portraiture.

I. Historical background

Rudolf Herzog has, with

great efforts, pieced together the known facts from

Nikias’ life[2].

One of his main achievements is the identification of Nikias the

tyrant with Nikias the philologist and thereby establishing his

early contacts with the spheres of power in Rome[3].

Suetonius characterizes him as an adherent of Pompeius and

Memmius, implying that he was in Rome with them until he was

reported transmitting a love letter of Memmius to Pompeius’

fifth wife. Through this he, together with Memmius, lost the

imperator’s favour and probably left Rome[4].

This episode of 52 BC shows that by this year, Nikias was not

only in Rome, but had already made contact with the powerful men

and women of the time. It is likely that the acquaintance with

Pompeius goes back to the triumphal journey of the imperator

through Asia and Greece after the third Mithridatic war[5].

After a significant

break due to Nikias staying in the East (where

exactly we do not know and Herzog’s assumption that

he went to Athens with Memmius is pure speculation[6]),

our sources mention him again towards the end of 50 BC, being on

his way to Rome in the company of Cicero, who mentions him in a

letter to Atticus as a fellow traveller[7].

From his return on he seems to have spent some time in the Roman

capital, where he again seems to have lived in exclusive

circles. Cic. ad fam. 7,23,4 mentions him in Rome in April 49 BC

and tells us that he is a friend of Cassius, the later

tyrannicide[8].

In 46 BC Cicero mentions Nikias again, this time as a friend of

Dolabella, the later consul[9].

That he could be a demanding guest and yet able to lead

cultivated conversations can be seen from a letter of 45 BC[10],

in which the orator mentions that he does not feel up to being

his host at that moment. Some months later he stayed with Cicero

again[11],

but soon left, being called urgently to Dolabella[12].

Late in 45 BC we find

Nikias in the entourage of this new patron. Cicero informs us

about the special honours Caesar bestowed on the latter, of

which he knew through Nikias[13].

The Coan seems to have been a very clever and opportunistic

personality with wide spread connections in Roman aristocracy.

This seems to have paid off, as we hear from Cicero that

Dolabella, consul since March 44 BC, had chosen Nikias as a

legate to go ahead of him to Greece and maybe Asia Minor to

prepare the war against the Parthians, who threatened the

eastern borders of the empire. By the middle of 44 BC we hear

that he is already in the east, though we do not know where[14].

Unfortunately, literary

sources are scarce from this point onwards. Strabo tells us that

»in my time«[15]

there was a Nikias on the island of Cos »who also reigned as

tyrant over the Coans«[16].

Since this Nikias is mentioned in a list of famous persons

consisting of a pair of scientists and a pair of literary

figures, he can with some confidence, as Herzog has ingeniously

shown, be identified with the Nikias we have so far heard about[17].

Unfortunately, literary sources mentioning him directly are

missing for these interesting years, but the fate of his island

in the time between Caesar’s assassination and the battle of

Philippi is – although scarcely documented – very telling.

Many cities and islands

of Asia Minor suffered in some way from the civil wars, either

by choosing the wrong sides or by being raided. Among these was

Rhodes, which not only had hosted Dolabella on his way to Asia

Minor, but had refused to lend support to the case of the

tyrannicides shortly after[18].

Thereafter the Rhodians first received a letter of Brutus,

warning them to surrender to him and Cassius voluntarily or

risking destruction of their city and slaughter of the male

population[19].

Apparently overestimating the own military power, the Rhodians

decided not to surrender, but first sent a fleet against

Cassius, which was defeated by the Romans in two battles, the

first of which became famous both through literary and

numismatic sources[20].

After this first defeat, a combined attack of naval and land

forces led to the siege and surrender of Rhodes, which had lost

almost its entire fleet.

Surprisingly enough, the

Coans obviously managed the situation much better than their

neighbours. The only literary sources for the year 42 BC, which

let us get a glimpse at the risky and yet successful political

manoeuvre that Cos managed to execute, are three of Brutus’

letters. The first one, written after the defeat of Rhodes,

calls on them to join the tyrannicides’ cause, again threatening

destruction and slavery[21].

From the second letter it becomes clear that Cos must have

decided to support Brutus and Cassius – at least ostensibly.

Brutus calls, in a slightly sharp tone already, for vessels that

the Coans have promised to build and send him as support in his

fight against the triumvirs. It is obvious that he had expected

the ships much earlier, which leaves one wondering about the

seriousness of the Coan offer. Brutus, however, seems to have

waited a while longer without receiving the promised naval

forces. In his third letter to Cos we learn that he has

dispatched a legation to the island to get the ships. His

legates reported to him that they were still under construction,

which resulted in him writing an angry and yet helpless letter,

accusing the Coans of having wasted too much time for their navy

to be of any use.

It can be deduced that

the Coans had managed on the one hand to come to terms with

Brutus, ostensibly supporting him by building a fleet, and on

the other to delay the construction of the promised vessels

without being severely punished for this clever manoeuvre. In

view of the fact that Nikias had been an acquaintance of Cassius

(and possibly Brutus) and is on the other hand known to have

been somewhere in the Greek east around these times, it seems

reasonable to assume that he had returned to Cos by that time

and was the mastermind behind the successful tactical

manoeuvring[22].

This point is strengthened by the evidence of honours bestowed

on him at an unknown time calling him son of the people,

homeland-loving, hero, benefactor and saviour[23].

The uniformity of the inscriptions and the small format of the

bases suggest that they were part of a publicly organised form

of honours for Nikias, involving the dedication of small-scale

statuettes in (probably) private contexts[24].

It is worth noting, however, that the epigraphic formula does

not imply a cult for Nikias as a god or demigod, but only

attests offerings pro salute /

ὑπέρ[25].

Having guided the island through the dangers of Roman civil war

and the interests of its imperators seems a suitable reason for

being honoured the way Nikias was[26].

Only two further facts

about Nikias are known. First of all, we know that at a certain

point he became tyrant of Cos[27].

Herzog thinks that the coins which will be discussed below and

the above-mentioned inscriptions and honours suggest that his

tyranny was not founded on force, but the circumstances as well

as the exact dating of his rule must remain uncertain[28].

It might be deduced from further examples in the east

Mediterranean that Nikias was among the rulers installed by

Antony after the battle of Philippi[29].

This would, if he had not established himself earlier, make it

probable that he came to power in 41 BC, maybe by being deployed

by Antony or confirmed by him. Whatever might be the case, we

know that Cos was on good terms with Antony, since the island

allowed him to seize timber (including from a holy grove of

Asklepios) for ships before Actium[30].

We also know of Roman citizenship and privileges in commerce

granted to a group of Coans by Antony at an uncertain date

probably in the early 30s BC[31],

making it probable that he maintained connections with the

island and its influential inhabitants.

We do not know much more

about the reign of Nikias. Apparently, he died at some point

late in the 30s BC, receiving an ordinary burial. After Antony’s

defeat at Actium, however, and maybe in connection with the

execution of Turullius for defiling the grove of Asklepios, the

Coans angrily reopened his grave, dragged the corpse out and

»killed him a second time«[32].

As a reaction, Octavian seems to have issued a decree to protect

tombs and the bodies of the diseased[33].

Apparently, the inhabitants of Cos were having their revenge on

Nikias for lining them up with the defeated party of the Roman

civil war[34].

II. Coinage

During Nikias’ reign,

coins with his portrait were issued by a variety of eight

magistrates whose actual function remains unclear[35].

It is usually assumed that they are eponymous magistrates, thus

indicating that the coins were minted over a span of at least

eight years, concluding that the tyrant’s reign lasted at least

from 38 to 31 BC[36].

However, Christian Habicht has shown that there is no reason to

assume that the magistrates signing the coins were the eponymous

ones or even yearly changing[37].

They can therefore not be used to date the reign of Nikias, nor

can they provide a pattern of minting. Vassiliki Stefanaki’s die

study furthermore found several connections of dies between

different magistrates, indicating that minting might to some

extent have happened in parallel[38].

We simply do not know if coins were emitted annually or not. A

date between the late 40s and 31 BC is hence the closest we get

at the moment. This is also in accordance with the numismatic

phenomenon of coinages of quartuncial standard appearing in the

eastern Mediterranean[39].

The coins in question

here are large bronzes engraved by skilled die cutters. The

weights, according to Stefanaki’s die study, range from 16,28 to

25,46 g with an average of 20,85 g (66 pieces). She has drawn

attention to the fact that with this average weight they fit

nicely into a variety of local and colonial coinages as well as

the so-called fleet coinage of Marc Antony, suggesting that the

coins were oriented towards the Roman numismatic and economic

sphere[40].

Diameters range from 30–33 mm and dies are fixed at 12 h. The

obverses show a portrait of Nikias to the right with the legend

ΝΙΚΙΑΣ[41],

the reverses are adorned with the bearded head of Asklepios to

the right, wearing a laurel wreath tied with a tainia. The

accompanying legends name the people (KΩΙΩΝ) and one of the

above-mentioned magistrates.

Since Stefanaki’s

thorough study of the issue, only few new examples have turned

up on the international market[42]

(table 1):

|

No |

Weight |

Dies |

Commentary |

Provenance |

|

1 |

22,75 g |

E9 / O15 |

Stefanaki 2012,

282 no. 2197; 494 fig. 2197 shows the closest parallel

(one correction has to be made in Stefanaki’s catalogue:

her numbers 2192 and 2193 cannot be from the same

obverse die). |

Gorny & Mosch Giessener

Münzhandlung, Auktion 181 (12.10.2009) no. 1782 |

|

2 |

19.24 g |

E14 / O28 |

Stefanaki 2012,

283 no. 2231; 498 fig. 2231 shows the closest parallel. |

Helios

Numismatik, Auktion 3 (29.04.2009) no. 56 |

|

3 |

21,42 g |

E16 / O37 |

Stefanaki 2012,

283 no. 2237; 499 fig. 2237 shows the closest parallel. |

Naville

Numismatics Ltd., Auction 31 (14.05.2017) no. 130; ex

E.E. Clain-Stefanelli collection |

|

4 |

24,95 g |

E4 / O12 |

|

Roma Numismatics

Ltd., E-Sale 31 (26.10.2016) no. 154 |

|

5 |

19,05 g |

E15 / O43 |

|

Roma Numismatics

Ltd., E-Sale 99 (07.07.2022) no. 407 |

The new examples do not

add anything new to the corpus in terms of magistrates or dies.

The main focus of this

paper is the iconography of the coins, more specifically the

iconography of their obverses, the reverse image being quite

straightforward and understandable in the context of Cos.

Concerning the portrait of Nikias on the obverses on the other

hand, some significant misunderstandings have dominated

scholarship up to now.

The first one concerns

the headdress. It is either interpreted as being a diadem[43],

a tainia[44]

or called an unspecific wreath, sometimes with a questionmark[45].

Kostas Buraselis wanted to identify it as some sort of knotted

(woollen) band, marking Nikias as being in some form sacred,

between the spheres of humankind and gods[46].

Andrew Burnett was, as

Buraselis also saw, certainly right with his verdict that what

we see on Nikias’ head »certainly does not look like a diadem«[47].

The diadem was a broad band, sometimes with decoration, tied on

the back of the head and ending in a straight form (not with a

pointed knot as a tainia)[48].

The differences to what is shown on these Coan coins are

striking. But it is also obvious that one main argument of

Buraselis is certainly wrong[49]:

The headdresses of Nikias on the obverse and Asklepios on the

reverse are certainly not the same. In addition, his

identification of the latter’s headdress as a twisted, knotted

headband is not correct. Burnett was right in identifying the

wreath of the god as a laurel wreath. It is, admittedly, a

slender one, with what seem to be two rows of laurel leaves very

closely together. And Buraselis might have seen something very

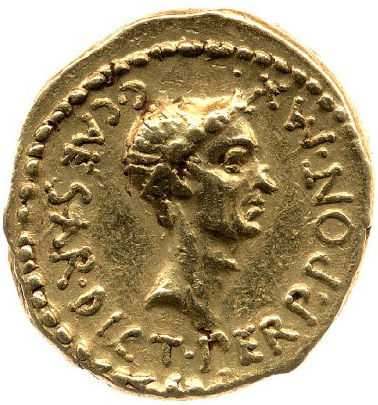

interesting, as a close examination of one of the better

preserved coins of the series shows (fig. 1). It looks as

if in regular intervals something is attached to the laurel

wreath, giving the impression of loops. In addition, it is not

tied with a tainia but with what seems to be a royal diadem.

This feature can be observed several times, but has not yet been

sufficiently explained[50].

However, the general picture of the main god of the island

wearing a laurel wreath remains valid.

If Nikias is not wearing

a diadem and not a ›Heroenbinde‹, two possibilities remain for

the identification of his headdress: a tainia or a wreath. Both

are correct, as is clearly shown by the enlargement of the

obverse of the coin shown above (fig. 2). Thin stalks and

leaves or needles emanating from a slim branch are easily

discernible. The wreath is, on the other hand, tied at the back

of the head with a tainia, actually making this a combination of

two insignia, a wreath and a tainia[51].

The plan used for the wreath is not easy to make out, given the

wear of the coins and the closeness in style of leaves and locks

of hair. The form of the leaves exclude that it is laurel. One

might think of Mediterranean cypress, as the sacred grove of

Asklepios on Cos consisted of cypress trees and it was centre of

cultic processions on the island[52].

The cypress was one of the sacred plants attached

to Asklepios[53].

The form of the twigs however seems to exclude an identification

as cypress, since they are not ramified enough[54].

The question as to which leaves are meant has to remain open.

The tainia is, both in Greek and Roman culture, sign of victory

and was therefore given to victors (both in real life as well as

in art, in many cases directly by Nike/Victoria)[55].

Building on this tradition we find examples of Hellenistic kings

shown wearing a combination of laurel wreath and tainia in

situations in which they seem to have been in some way

victorious or successful[56].

Nikias could therefore be marked, with the combination of a

wreath and tainia, as both victorious and as a worshipper, maybe

even a cult member, of Asklepios[57].

Nikias’ portrait has

already received some scholarly attention, especially by Burnett[58]

and Buraselis[59].

As the latter observed quite correctly, the wear of most of the

examples of the coins makes it difficult to derive all the

necessary details of the head from only one coin. The plates in

Stefanaki’s publication are certainly helpful to get a general

overview, although one has to admit that the print quality is

not too high[60].

The following description is based on a combination of several

pieces of above average preservation in enlargements (figs.

2–5).

The skull, structurally

defined by its bones, is mounted on a narrow, sinewy neck with a

prominent Adam’s apple. The back of the head is regularly

rounded, whereas the face from the small pointed chin to the

very high forehead is quite flat. A marked break is formed by a

big, hooked nose with a protuberance marking it might have been

broken at one point. From its sides, long and deep nasolabial

folds stretch towards the sides of a narrow mouth formed by

regular lips, itself accompanied by sharp folds. The bulging

brows are knitted above the nose, contracting with them the high

forehead, leaving one or two parallel wrinkles across it. Thin,

finely cut eyelids cover almond-shaped eyes while the lower

eyelid fades into a slender lacrimal. Sharply incised, short

crow’s feet complete the carefully composed eye region. The hair

consisting of slim, curved locks emerges from a swirl on the

back of the head. Over the forehead the sparse locks of hair

form quite a well-defined hairstyle. Three strands are combed

forward into the forehead, as if to hide a gradually growing

baldness. Towards the right temple they are followed by a lock

forming an S and four further locks simply curved downwards over

the elongated ear. Cheeks, chin and upper lip are covered by a

short, regularly trimmed beard. The head is adorned, as stated

above, with a combination of wreath and tainia.

This portrait, with

clear traits of verism, smooth and taut skin as well as

contractions as marks of concentrated effort, fits well into a

line of late Hellenistic royal portraiture as defined by rulers

like Antiochos I, Orophernes, Hiero II or Philetairos[61].

In Nikias’ lifetime, this style of portraits was popular in

Rome, while also clearly having Greek roots, both in civic and

royal portraiture[62].

Recent scholarship has

more or less unanimously concluded that Nikias’ portrait was

influenced by the early portraits of Octavian[63].

This is, on the one hand, politically unlikely, given the fact

that Cos in general and Nikias in particular

maintained connections with Antony[64].

Furthermore, it would have been unwise, even if there had been

no direct connection between the island and the imperator, to

show too much sympathy with the cause of Octavian in the realm

under Antony’s rule.

Apart from these

arguments, Octavian’s portraits are also markedly different in

style and conception from those of Nikias. First of all it is

quite obvious that there is no similarity with or dependence on

the portraits of the so-called Octavians-Typus[65].

Two schemes of portraits remain in discussion[66].

Scheme I was used for

coins between 43 and 38 BC and its portraits are characterized

by a youthful, smooth and unspecific physiognomy. The round

heads show a full, almost chubby integument, a long pointed

nose, a small chin slightly bent upwards and a small,

full-lipped mouth. A closed, even cap of short, straight locks

encloses the head[67].

(figs. 6–8)

Since 42 BC, scheme II

was in use in parallel with scheme I. Its portraits were minted

until 36 BC – after 40 BC, in parallel with the first portraits

of the ›Octavians-Typus‹ – when the so-called

Siegesserie marked a turning point both in the depiction of

portraits on coins[68]

as well as in the history of the treatment of portraits in

general – from a more general scheme which was not copied in

every detail to a portrait type with copies as exact as possible[69].

The physiognomic characterization of the portraits is the same

as with coins of scheme I. The variation can be found in the

hairstyle, as the portraits of scheme II show a role of hair at

the neck of the head and above the forehead. Both are more

voluminous than the rest of the hair, which is evenly combed

downwards in straight locks again[70].

(figs. 9. 10)

The brief overview of

coin portraits of both schemes shows clearly, that on the one

hand the characteristics are very generic and that on the other

hand the exactness of the execution by the die cutter varies

very much. The extreme youthfulness makes it impossible to

conclude that the Octavian portraits influenced that of Nikias.

The only parallel might be the beard sometimes attached to

Octavian’s image. But, on the other hand, an examination of the

bearded portraits of Octavian demonstrates that these show a

wide range of different beards with probably different meanings[71],

making it very difficult to find a reason why Nikias should have

copied this specific form of a beard.

It was already mentioned

that the underlying style of portraiture to which Nikias

referred was also used by some Romans. Among these, we easily

find one whose portraits show parallels to that of the Coan:

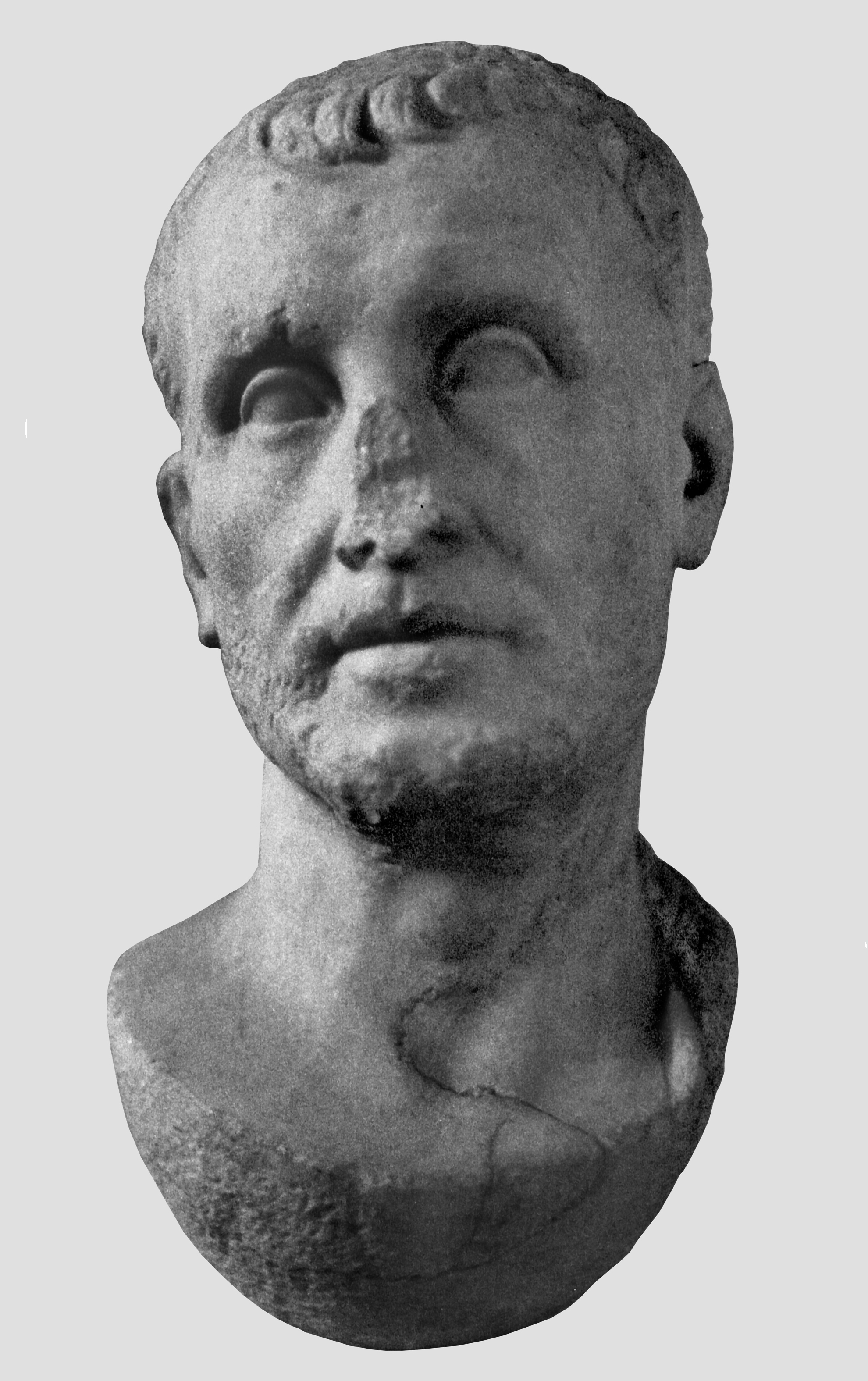

Mark Antony (figs. 11–13). Especially coins of 42 BC,

when his portraits still wore a mourning beard[72],

reveal astonishing parallels: the head has a similar general

structure; the hair consists of even locks which form clear

patterns across the forehead, the latter being divided by at

least one wrinkle; the brows contracted above the nose which is

quite big and slightly hooked; the use of mild verisms[73].

These similarities

clearly indicate, from my point of view, that the model

for Nikias’ portrait was that of Mark Antony. This makes Nikias

a forerunner of later client kings[74],

modelling their portraits according to that of Augustus[75].

Probably having come into his position only a short while before

having these coins minted, with at least Antony’s approval if

not his support, Nikias showed that he was a philoromaios and a philantonius with his

portrait. On the other hand, the traits of the portrait all

stemmed from a Greek tradition, fitting the likeness into the

line of Hellenistic royal portraiture.

III. Searching

for a sculptural portrait

Attempts to identify

a sculptural portrait of Nikias have been extremely scarce[76].

The marble bust of a boy with the inscription NIΚIΑΣ ΤΥΡΑNNΟΣ is

probably, should the inscription be ancient, a creation of later

times, when somebody wanted to recreate a representation of the

dead[77].

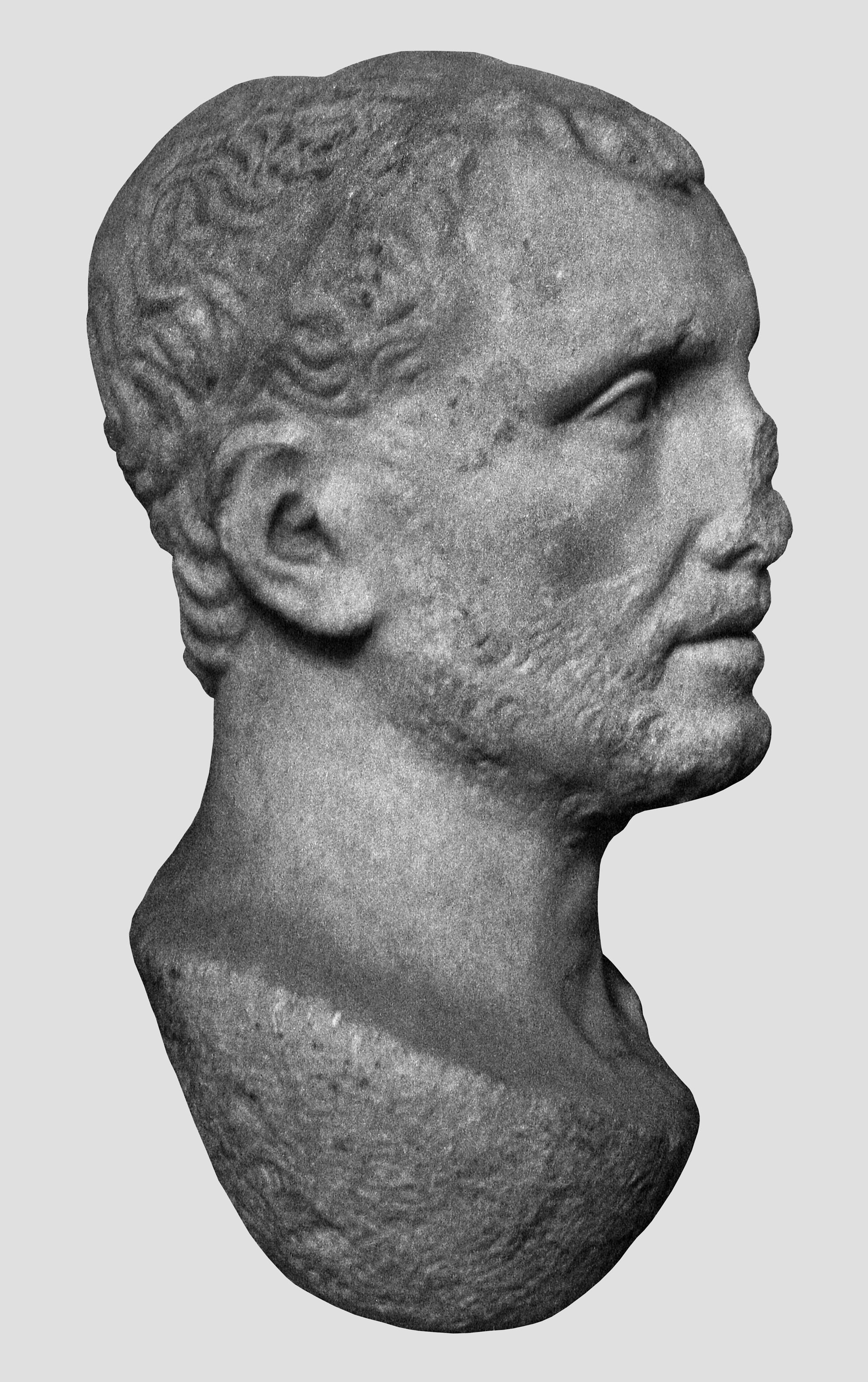

Dieter Salzmann has,

hesitantly[78],

drawn attention to the fact that there are similarities between

the discussed coin portrait and a marble one in the

Archaeological Museum of Rhodos[79]

(fig. 14). It is usually identified as Poseidonios which

cannot be true due to the fact that the person depicted is much

younger, has a distinctly different facial profile and lower

face and much more stylised eyes[80].

The portrait shows a

middle-aged man with markedly veristic features and wide open,

strongly stylized eyes. The receding forehead shows deep

wrinkles, the broken nose seems to have been hooked, that mouth

is girded with a deep cut. The hair is styled in small curls,

reaching down deeply in the middle of the forehead and receding

acute-angled towards the sides. The head shows traces of a band

probably added in metal.

In comparison with

Nikias’ portrait on the coins, the similarities one finds in the

lower section of the head (chin, mouth, nasolabial section,

cheek, nose) are soon weighed out by clear differences.

Especially three features prohibit an identification: the

profile line of the face is markedly different; the forehead of

the marble head is receding while that of the coin portrait is

steep; and the hairstyle shown on the coins lacks the

characteristically receding hairline of the marble portrait. The

Rhodian portrait can therefore not be identified as Nikias of

Cos, despite the fact that in these times one cannot yet expect

the accuracy of later portrait types[81].

IV. Concluding

remarks

Nikias of Cos is one

of the quickly rising and quickly falling illustrious characters

of the civil war Mediterranean between the mid-40s and 30 BC.

Obviously opportunistic, intelligent and eloquent, he managed to

get in touch with and become a close acquaintance of most of the

powerful Romans at that time. His cleverness not only allowed

him to manoeuvre his homeland through most of these difficult

times, he also built himself a nice position as a tyrant,

receiving high honours on Cos. The exact time at which this

happened is unclear. If we accept Antony’s coins of 42 BC as

direct models for Nikias’ portrait, we can assume that shortly

after this year, Nikias’ regime was established and his coinage

minted. How long it lasted is equally unsure, but around 31 or

30 BC it seems to have ended with Nikias’ death, burial and the

desecration of his tomb.

His portraits show

on the one hand his close connection with Antony while marking

him on the other as a Hellenistic ruler. The headdress, a wreath

with a tainia, probably connects him with the cult of the main

god of the island, Asklepios, figuring on the reverse of the

coins, and marks him as victorious. The coin series, as we see,

embodies the complete political programme of a small tyrant

between Hellenistic kingdoms, Rome and his homeland, trying to

find his place in the dangerous times of the civil war which was

sweeping over the whole Mediterranean world.

*

Again, a variety of colleagues and

friends have helped me during the work on this paper.

For discussions, literature, and a variety of hints I

thank Sebastian Whybrew, Tobias Esch, Simone Killen,

Vassiliki Stefanaki, Despoina Nikas, Frank Daubner,

Dieter Salzmann and Andrew Burnett. Of course, all

remaining mistakes are mine.

[1]

Literature on Nikias is not abundant. The most complete

account of his career is still Herzog 1922, 190–216.

Research has since then not produced significant new

results concerning the reconstruction of his life and

career, which clearly reflects the lack of extent

sources; compare Syme 1961, 25–28; Bowersock 1965, 45

f.; Sherwin-White 1978, 141–145; Buraselis 2000, 30–65

(criticism of his analysis of Nikias’ coinage below). D.

Salzmann has, in his unpublished Habilitationsschrift,

dealt with Nikias’ coinage and portrait; Salzmann 1986,

184–187 (corpus of coins). 239–243 (analysis). A

detailed study of his coinage (including a die study)

has recently been published by V. Stefanaki; Stefanaki

2012, 126–130. 281–283 series XIX emission 51. I am

grateful to her for sending me a scan from

that publication.

[2]

Herzog 1922.

[3]

Herzog 1922, 191. Nikias’ youth and his

family remain unknown. In a later anecdote it is

mentioned that an ewe belonging to Nikippos (= Nikias)

once gave birth to a lion, thereby predicting him future

kingship while he was still an ordinary person; Ael.

Poik. 1,29: λέγουσι Κώων παῖδες ἐν Κῷ τεκεῖν ἔν τινι

ποίμνῃ Νικίου τοῦ τυράννου οἶν: τεκεῖν δὲ οὐκ ἄρνα ἀλλὰ

λέοντα. καὶ οὖν καὶ τὸ σημεῖον τοῦτο τῷ Νικίᾳ τὴν

τυραννίδα τὴν μέλλουσαν αὐτῷ μαντεύσασθαι ἰδιώτῃ ἔτι

ὄντι. Deducing from the episode that he was a shepherd

guarding other people’s animals and not owning any

cattle is not probable; contra Buraselis 2000, 38 f.

Certainly his family must have been at least of some

standing and income as their son could become a

philologist; cf. Sherwin-White 1978, 142.

[4] Suet.

gramm. 14: Curtius Nicias haesit Cn. Pompeio et

C. Memmio; sed cum codicillos Memmi ad Pompei

uxorem de stupro pertulisset, proditus ab ea,

Pompeium offendit, domoque ei interdictum est;

»Curtius Nicias was an adherent of Gnaeus Pompeius and

Gaius Memmius; but having brought a

note from Memmius to Pompey’s wife with an infamous

proposal, he was betrayed by her, lost favour with

Pompey, and was forbidden his house« (translation: J. C.

Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library, Suetonius II, 1914). That

he left Rome with Memmius is suggested by Herzog 1922,

194 since for some years our sources do not mention him.

[5]

Herzog 1922, 191.

[6]

Contra Herzog 1922, 194.

[7] Cic.

ad Att. 7,3,10. Whether he was an old acquaintance of

Cicero and Atticus, as Herzog 1922, 195 suggests, cannot

be deduced from the letter.

[8] For

the identification of this Nikias see Herzog 1922, 196

n. 1. He also must have closer contact to Brutus, as can

be restored from Cic. ad Att. 13,9; Herzog 1922, 203.

[9] Cic.

ad fam. 9,10. Compare Suet. gramm. 14.

[10] Cic.

ad Att. 12,26,2.

[11] Cic.

ad Att. 12,51,1. 53.

[12] Cic.

ad Att. 13,1,3.

[13] Cic.

ad Att. 13,52,2.

[14] Cic.

ad Att. 14,9,3; 15,20,1.

[15] The

material for the Geographica seems to have been

collected mainly between the years 20 and 7 BC. The

formulation must not mean that Nikias was a tyrant in

that time (which is unlikely considering his coinage).

Strabo was in Rome from 44 BC onwards and was presumably

well informed about the political events during the

civil war, especially those concerning Greece; Lasserre

1979.

[16]

Strab. 14,2,19.

[17]

Herzog 1922, 206–208.

[18] App.

civ. 4,66–70.

[19] As

had been the case in Xanthos, according to Brutus. Text

and translation of the letters have been compiled in

English by Jones 1994 (the letter to Rhodes ibid. p. 224

f.), who also convincingly argues for the letters to be

authentic. As to this question, I share the view brought

forward by Bengtson 1970, 37 f., Jones 1994 and others

that the letters themselves are indeed genuine, though

the answers are probably not.

[20] For

example, App. Civ. 4,71; Cass. Dio 47,33. Several coins

refer to the event with their images or details of

imagery. They have been discussed in detail by Hollstein

1994, 122–126. See also Woytek 2003, 505–528; Biedermann

2018.

[21]

Jones 1994, 226 n. 26.

[22]

Herzog 1922, 211 f.

[23] Cf.

the inscriptions on bases of statuettes offered to the

θοὶς πατρᾡοις for Nikias’ well-being: Paton – Higgs

1891, nos. 76–80; IG XII, 4, 2, 682. 683. 685–690. 692.

695. 697–704. 706–711. For the phenomenon of dignitaries

dominating politics in Hellenistic cities with (for some

time at least) the consent of their fellow citizens,

which lead to exclusivity in politics and the tendency

to a dynastic trend in civic offices see Scholz 2008;

Daubner 2021 (with examples from Kalindoia).

[24] For

similar practices in Hellenistic kingdoms see Kyrieleis

1975, 137. 145; Dahmen 2001, 10 f. with examples. For

the difficulty in specifying these ›private‹ contexts of

small-scale sculpture see the summarizing remarks in

Schreiber 2016, 127–129. There is, however, no evidence

for the assumption that Nikias demanded or installed a

cult; contra Taeger 1957, 356 f.

[25]

For this distinction

see Pfeiffer 2008, 31–33. For dedications of statuettes

and statues of the dedicators see Himmelmann 2001. The

phenomenon of dedicating a statue of one god to another

discussed by Chaniotis 2003a, 431–433 with further

literature; Chaniotis 2003b, 11 f. with some examples

from Roman imperial cult. Grammar of dedications and its

change: Veyne 1962; Ma 2007; Kajava 2011, 562 f. with

further literature.

[26]

Herzog 1922, 208–212. Compare the honours for Theophanes

and Potamon at Mytilene: Pawlak 2020; Salzmann 1985

(concerning the portrait of Theophanes); Taeger 1957,

369 f.

[27]

Strab. 14,2,19.

[28]

Contra Herzog 1922, 208.

[29] Cf.

Boethos of Tarsos (Strab. 14,5,14); Straton of Amisos

(Strab. 12,3,14). For all these measures and further

examples see (especially for the instalment of new

client kings) see Raillard 1894; Buchheim 1960, 11–28;

Magie 1950, 427–436.

[30]

Cass. Dio 51,8,3.

[31] The

text of the statute is damaged and incomplete. At some

point the name of the triumvir was erased and the stele

smashed to pieces. M. Crawford rightly points out that

the latter must not necessarily have happened in

antiquity; the completest publication of the inscription

Crawford 1996, 497–506; see also Buraselis 2000, 25–30.

[32]

Krinagoras of Mytilene, AP IX.81:

Μὴ εἴπης

θάνατον βιότου ὅρον· εἰσὶ χαμοῦσιν

ὡς ζωοῖς ἀρχαὶ

συμφορέων ἕτεραι.

Ἄθρει Νικίεω

Κῴου μόρον· ἤδη ἕκειτο

εἰν Ἀίδη,

νεκρὸς δ’ ἦλθεν ὑπ’ ἠέλιον·

ἀστοὶ γὰρ

τύμβοιο μετοχλίσσαντες ὀχῆας

εἴρυσαν ἐς

ποινὰς τλήμονα δισθανέα.

»Tell me not that death is

the end of life. The dead, like the living, have their

own causes of suffering. Look at the fate of Nicias of

Cos. He had gone to rest in Hades, and now his dead body

has come again into the light of day. For his

fellow-citizens, forcing the bolts of his tomb, dragged

out the poor hard-dying wretch to punishment«.

Translation W. R. Paton, The Greek Anthology III, Loeb

Classical Library (New York 1915) p. 43.

The date of

the epigram has to remain unsure; Geffcken 1922, 1861.

[33] SEG

8.13. For the provenance of the inscription see Harper

et al. 2020.

[34] Cos

was fined by Octavian for taking the side of Antony;

Herzog 1922, 215 with sources.

[35] RPC

I, nos.

2724.

2725.

2726.

2728.

2729.

2730.

2731;

Stefanaki 2012, 126–130. 281–283. The following

magistrates are attested: ΧΑΡΜΥΛΟΣ, ΠΟΛΥΧΑΡΗΣ,

ΟΛΥΜΠΙΧΟΣ, ΚΑΛΛΙΠΠΙΔΗΣ, ΕΥΚΑΡΠΟΣ, ΕΥΚΑΡΠΟΣ, ΔΙΟΦΑΝΤΟΣ

and ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΣ.

[36]

Herzog 1922, 208; Syme 1961, 27 n. 68; Sherwin-White

1978, 144; Stefanaki 2012, 126.

[37]

Habicht 2000, 322–326. The study of the coinage between

the fourth and second century BC by H. Ingvaldsen

reached a similar conclusion; Ingvaldsen 2002, 187–206.

[38]

Stefanaki 2012, 126.

[39]

Stefanaki 2012, 129. For the phenomenon in general

compare Kroll 1997.

[40]

Stefanaki 2012, 127–130. For the ›fleet coinage‹ see v.

Bahrfeldt 1905; Buttrey 1953; Amandry 1986; Amandry

1987a; Amandry 1987b; Martini 1988; Amandry 1990; RPC I,

p. 284 f. nos.

1453–1461.

1462–1470.

4088–4093;

Kroll 1997, 124. 128 f.; Fischer 1999, 191–211; Amandry

2008; Amandry – Barrandon 2008, 230–232.

[41] The

only surviving examples of his portraiture, since the

small bust (»bustino«) of a child with the inscription

NIΚIΑΣ ΤΥΡΑNNΟΣ has to be considered depicting somebody

else and the inscription incised at a later point;

original publication Jacopitch 1928, 95 fig. 77. The

bust was in the ›Castello dei Cavalieri‹ of Cos and was

recorded during a restoration campaign 1915–1916, during

which a catalogue of over 1300 marble artefacts was

collected. The pieces came from a variety of findspots

and collections more or less all over the island of Cos;

Jacopitch 1928, 92. Buraselis 2000, 41 n. 61 states he

was not able to trace the piece. It has to be considered

lost.

[42] Dies

are indicated according to Stefanaki’s system; Stefanaki

2012, 281–283. Some of the coins collected by her have

continued their journey through private collections and

auction houses: Stefanaki 2012, no. 2184α = Bertolami

Fine Arts, ACR Auctions, Auction 4 (05.12.2011) no. 7;

Stefanaki 2012, no. 2231 = CNG, Electronic Auction 145

(09.08.2006) no. 95 = CNG, Electronic Auction 490

(21.04.2021) no. 23; Stefanaki 2012, no. 2198 = Fritz

Rudolf Künker GmbH & Co. KG, Auktion 333 (16.03.2020)

no. 318; Stefanaki 2012, no. 2224 = Gemini LLC, Auction

10 (13.01.2013) no. 118; Stefanaki 2012, no. 2205 =

Stacks, Bowers and Ponterio, January 2017 NYINC Auction

(12.01.2017) no. 2057 (in her list The New York Sale 11

[11.01.2006] no. 202 is missing for this coin).

[43] BMC

Caria, 213 no. 196–200; Sherwin-White 1978, 142.

[44]

Stefanaki 2012, 126. 281.

[46]

Buraselis 2000, 31–33. He clearly has in mind the

so-called Heroenbinde, which should have a different

form; Martin 2012.

[47] RPC

I, p. 452; Buraselis 2000, 31.

[48]

Salzmann 2012.

[49]

Buraselis 2000, 32.

[50]

Compare Salzmann 2012, 358 n. 83; Martin 2012, 270 with

some examples.

[51] For

the combination of tainia and laurel wreath, focussing

on Roman iconography, see Biedermann 2020.

[52]

Ps.-Hippokr. Ep. 11 (Smith 1990, 58–61); Sherwin-White

1978, 339. Unfortunately, cypress is nowhere attested to

have played a role in the cult of the healing god. Olck

1901, 1915–1938 for the cypress in cult, esp. 1923–1932;

cypress in medicine 1913–1915. Attested as plants for

wreaths in connection with the cult of Asklepios are

olive, laurel and oleander; Nilsson 1906, 410; Blech

1982, 312.

[53]

Ps.-Hippokr. Ep. 11; Thraemer 1886, 628.

[54] I

thank Cathy Lorber for doubting my earlier

identification and Thibaud Messerschmid as well as Simon

Pfanzelt (both Botanischer Garten München-Nymphenburg)

for their botanical expertise.

[55] See

for example Lehmann 2012; Biedermann 2020, esp. 34–41.

[56]

Biedermann 2020, 25 f. 40 f.

[57] We

do not know what the insignia of the priests and other

cult personal looked like; Ps.-Hippokr. 11.

[58] RPC

I, p. 452.

[59]

Buraselis 2000, 31–35.

[60]

Stefanaki 2012, pl. 493–499. 514.

[61]

Salzmann 2012, 362–379 for a quick overview of

numismatic sources. A sculpture with a bearded portrait

interpreted frequently as a Greek, the so-called

Thermenherrscher, has convincingly been identified as Q.

Caec. Metellus Macedonicus by Stephan Lehmann; Lehmann

1997.

[62]

Among the Roman portraits those of Marcus Antonius

(Biedermann 2018, 18–43), Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Trunk

2008), Sextus Pompeius (Biedermann 2018, 697–703),

Lucius (?) Ahenobarbus (Lahusen 1989, 28 f.) or, as a

late example, that of Agrippa (Fittschen et al.

2010, 29–33 no. 16, esp. p. 30) can be

named. For the conventions behind this style of

portraiture Zanker 1976; Zanker 1978, 34–39; Balty 1982;

Lahusen 1989, 75–81; Fittschen 1991a (opposing Giuliani

1986). Bearded Greek and Roman private portraits with

veristic traits along these lines are known en masse

from intaglios and cameos from the second and first

centuries BC; compare Vollenweider 1974, 25, 1–7; 44, 1;

45, 1; 129, 1–12 (interpreted as Greeks) and Biedermann

2013 with Roman examples. Bearded and veristic royal

portraiture collected by Iossif – Lorber 2009, focussing

on Seleucid examples, but including others too.

[63] RPC

I, p. 452. Buraselis 2000, 31.

[64] See

above and Herzog 1922, 212 f.; Sherwin-White 1978, 145;

Crawford 1996, 497–506 (text and commentary of the

lex fonteia); Buraselis 2000, 25–30.

[65] For

the portrait type in general see Brendel 1931, 40–54;

Curtius 1940, 47–53; Zanker 1978; Hausmann 1981,

535–550; Massner 1982, 32–36; Boschung 1993, 11–22. 61

f.; Fittschen – Zanker 1994, 1 f. no. 1; Fittschen 1991,

161–163

[66] For

the following division into schemes and the coin types

showing these portraits Biedermann 2018, 260–310 esp.

295–301. For the term ›portrait scheme‹ in contrast to

›portrait type‹ Biedermann 2018, 15–17.

[67] For

the complete account of types cf. Biedermann 2018, Oct.

M 1–16. 32. 33 (figs. 550–621. 742–764).

[68] The

series is, as far as I see, the first example in which

the three-dimensional prototype was depicted from both

sides.

[69]

Biedermann 2018, 15–17. 260–310 esp. 295–301.

[70] For

the complete account of types see Biedermann 2018, Oct.

M 18. 20–22. 38. 40. 41; figs. 628–644. 648–685.

808–829. 831–853.

[71]

Biedermann 2013, 35–38; cf. Hertel 2021 now with partly

differing results.

[72]

Biedermann 2013, 38–44; Biedermann – Haymann 2015, 301

f.

[73] For

the types cited here Biedermann 2018, Ant. M 15. 16. 18.

For Antony’s portrait and the schemes in general compare

Biedermann 2018, 18–43.

[74]

Another early example is Tarcondimotus I of Cilicia,

whose portrait is clearly influenced by that of Caesar

(the huge amount of wrinkles, crow’s feet, leather-like

skin and bony substructure of the face) while at the

same time picking up what seem to be elements of the

›antonian‹ style of portraiture, namely in the even,

curly, short hair and the muscular, thick neck. He seems

to have been born around 100 BC, having thus reached an

age of probably between 50 and 70 years before he was

installed as a client king by Antony; Wright 2009, 74.

For Tarcondimotus I and his coinage see RPC I, no.

3871;

Sayar 2001, 373–375; Tobin 2001 (focus on the dynasty);

Wright 2008, esp. 115–118; Wright 2009 and Wright 2012

(with focus on the contacts of his dynasty with the

Romans).

[75] The

most prominent example being Juba II; cf. Salzmann 1974;

Fittschen 1974. Dahmen 2010 gives a great general

overview if the phenomenon.

[76] That

there must have been portrait statues is proven by a

base found on Cos which according to its measurements

once carried a statue; Herzog 1899, 67. 128 Nr. 192.

[77] For

the bust and the identification see Jakopitch 1928, 96;

Sherwin-White 1978, 142 n. 323. Discussion and

falsification Salzmann 1986, 243.

[78] I

thank Dieter Salzmann for drawing my attention to the

head and discussing it with me.

[79]

Salzmann 1986, 242 f. Archaeological Museum of Rhodos,

inv. E48. For a discussion of the head and a

bibliography see Bairami 2017, Kat. 068.

[80]

Salzmann had already recognized that the head follows

(as do the coin portraits discussed here) the same style

of portraiture as that of Poseidonios; Salzmann 1986,

242.

[81] See

above, note 69.