A Special Tetradrachm Series of Euthydemos I

Abstract: In this

paper, tetradrachms of Euthydemos I of Bactria are discussed

that differ from the regular coinage of the king: The most

striking difference is the frontal glance of the seated Herakles

depicted on the reverse. While other scholars have regarded

these tetradrachms as posthumous, it is proposed that they were

minted during Euthydemos’ lifetime, possibly during the war with

the Seleukid king Antiochos III.

Keywords: Bactria

(http://nomisma.org/id/bactria),

Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom (http://nomisma.org/id/bactrian_kingdom),

Euthydemos I (http://nomisma.org/id/euthydemus_i_bactria),

Antiochos III (http://nomisma.org/id/antiochus_iii),

Herakles (https://d-nb.info/gnd/118639552)

Zusammenfassung:

In diesem Beitrag werden Tetradrachmen des Euthydemos I. von

Baktrien behandelt, die sich von den regulären Münzen des Königs

unterscheiden: Der auffälligste Unterschied ist der frontale

Blick des auf dem Revers abgebildeten Herakles. Obwohl andere

Forscher diese Tetradrachmen als posthum bezeichnet haben, wird

vorgeschlagen, dass sie zu Euthydemos’ Lebzeiten geprägt wurden,

möglicherweise während des Krieges mit dem Seleukidenkönig

Antiochos III.

The Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom, covering

the northern parts of present-day Afghanistan and southern

Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, was founded by Diodotos I.

The satrap of Bactria and Margiana gradually increased

the independence of his rule and when his Seleukid overlords

were weakened by the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC), he assumed

the royal title[1].

The Diodotid dynasty came to an end around 225 BC, when the

founder’s son, Diodotos II, was overthrown by Euthydemos I.

Euthydemos was one of the most important Graeco-Bactrian kings:

His greatest achievement, as narrated by Polybios[2],

was the repelling of Antiochos III’s invasion (208–206 BC) –

this lead to the recognition of his status by the Seleukid

monarch and paved the way for the subsequent expansion of the

kingdom south of the Hindukush[3].

During his long rule, which lasted until c. 200 BC, Euthydemos I

produced an abundant silver coinage: All of his tetradrachms

depict Herakles, the main god of the Euthydemid dynasty, seated

left on a rock. This image could have been influenced by

tetradrachms of the Seleukid kings Antiochos I and II, which

display a largely identical motive and were, inter alia, minted

in Magnesia on the Sipylos, Euthydemos’

possible hometown[4].

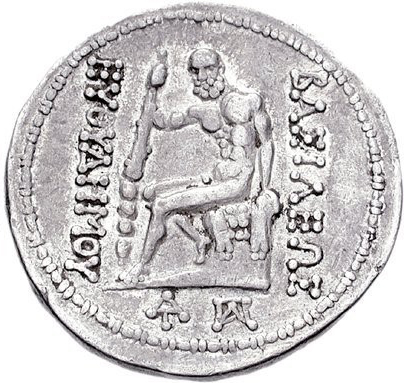

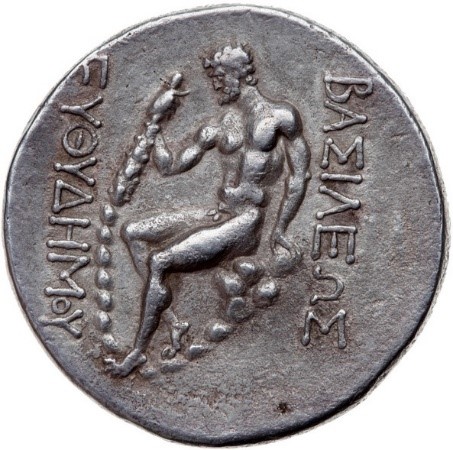

There is, however, a series of tetradrachms that differs from

the regular silver coins of Euthydemos I in some aspects. Only

few coins of this type have survived: Four specimens – in the

collections of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (no.

R 3681.30), the American Numismatic Society (SNG

ANS, no. 180), Aman ur Rahman (Bopearachchi –

Rahman 1995, no. 117) and Klaus Grigo (fig. 1) – have the

monograms

![]() and

ΔΙ in

the exergue, another example – sold by Classical Numismatic

Group (fig. 2) – has

and

ΔΙ in

the exergue, another example – sold by Classical Numismatic

Group (fig. 2) – has

![]() and

and

[5].

Osmund Bopearachchi regards these tetradrachms as Sogdian imitations, noting the unusually large diameters of their flans (ranging from 31 to 34 mm)[6]. While it is true that such sizes are first attested under Demetrios I (c. 200–190 BC), the temporal distance should not be problematic if the tetradrachms were minted in the latter half of Euthydemos’ reign. Olivier Bordeaux suggests that the series might have been issued by Eukratides I (c. 170–145 BC) because two of the monograms also appear on his coinage[7]. But against this speak the legend conventions on other Bactrian commemorative coins, which are discussed in more detail below. As the artistic quality, weight and fixed die axis (6 or 12 o’clock) are all compatible with official issues of Euthydemos I, the following contribution will further investigate the idea that the tetradrachms were minted during his lifetime.

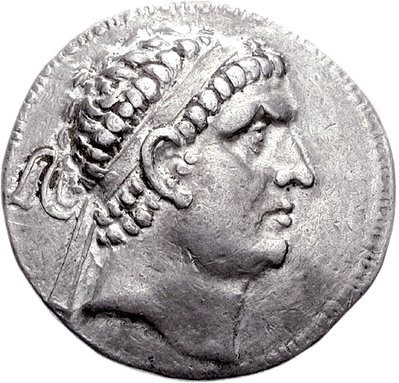

Comparison with Euthydemos’

coinage

First, we shall take a closer look at the iconographic details of the unusual tetradrachm series. As Bordeaux has observed, the diademed head on the obverse strongly resembles the portraits on some of Euthydemos’ tetradrachms which he classified as Group I (fig. 3)[8]. The heads are nearly identical, except that the left diadem end is arranged differently. The reverse shows the bearded Herakles seated left on a rock with the skin of the Nemean lion draped on it, resting the club in his right hand on a pile of stones. This motive is very similar to the standard reverse design of Euthydemos’ precious metal coins. Yet there are some differences. The most notable is the placement of the hero’s head: It looks directly at the user of the coin, whereas on the rest of Euthydemos’ coinage it is turned to the left. This is not the first case of a god on a Bactrian issue being depicted with a frontal glance. That would be the Athena on the bronze coins of Diodotos I/II, but note that the goddess is standing frontally[9]. A frontal glance combined with a body partially or entirely turned in profile is an unusual sight. Apart from the tetradrachm series in discussion, it only occurs with the king on horseback, depicted on the drachms of Antimachos II (c. 168–165 BC)[10], and with the second mounted Dioskour on Eukratides I’s coinage[11].

Our group of tetradrachms depicts Herakles setting his club on a pile of five round rocks. On the precious metal coins that Euthydemos I struck between c. 225 and 208 BC, the club is also set on a pile of stones (Bordeaux Groups A1–H2); this was removed on the later series, where the hero rests his club on his right knee or thigh (Bordeaux Groups I1–K6). On the majority of the coins, the pile is formed by three larger rectangular rocks. There are, however, two series of tetradrachms which display several small round rocks (Bordeaux Groups E3, H2; fig. 4–5), resembling the depiction on the unusual tetradrachm series. The latter presents the rock on which Herakles is sitting as a throne-like structure, corresponding to the designs on Bordeaux Groups I1–K6; these coins also have the lion skin draped on the rock, which is absent on the earlier groups. On the regular series, Herakles rests his left hand on a ledge that is distinctly developed on the upper right corner of the block; this detail goes back to Groups H1–2 (fig. 5), the last to feature a naturally formed rock without lion skin. It is visible on all coins of Groups H to K – albeit less pronounced on the gold octadrachm (Group J1) –, but missing on the unusual tetradrachm series.

Comparison with later coins

Let us also consider the later

iterations of Euthydemos’ seated Herakles. On the commemorative

tetradrachms issued by the Bactrian kings Agathokles (c. 185–178

BC) and Antimachos I (c. 178–170 BC), Herakles sits on a

naturally formed rock without the lion skin draped on it, his

left resting on a more or less pronounced ledge, the club set on

a single rock behind his right knee (fig. 6)[12].

A tetradrachm with the reverse legend EYΘYΔHMOY MEΓΑΛOY (»of

Euthydemos, the Great«) follows the same iconography, only the

club is set on the hero’s right knee. This issue could be an

early prototype for Agathokles’ commemorative series[13].

The motive is also repeated on square bronze coins, struck in

the late second century BC by the Indo-Greek queen Agathokleia

and her son or husband Strato I. They show Herakles sitting on a

big rock without lion skin, resting his club on his right knee (fig.

7)[14].

On the coins of the Indo-Scythian rulers Azes, Azilises,

Spalahores and Spalagadames (mid first century BC), the diademed

Herakles sits emphatically on a small rectangular rock and holds

the club closely to his face[15].

The iconographic analysis has shown

that the unusual tetradrachm series fits quite well into the

regular coinage of Euthydemos I: The stone pile is reminiscent

of Bordeaux Groups E3 and H2, the lion skin finds parallels in

Groups I to K and is notably absent from the posthumous

utilizations of the type. Moreover, the commemorative coins

repeating the types of Euthydemos I display different legends

than our tetradrachm series: They always name Euthydemos with

his epitheton Theos (or Megas on the prototype

issue), but without the royal title (fig. 6); the

commemorative tetradrachms also give the name of the issuing

king, introduced with ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ (»during the kingship of«).

The fact that the unusual tetradrachms do not name any other

minting authority except Euthydemos I, who is referred to as

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ like on his regular coinage, strongly

suggests that they were minted during the king’s lifetime. An

important indication for dating the series is the close

similarity to the portraits of Group I. Group I is a substantial

coinage (Bordeaux records 147 examples) and was probably minted

in the years before the war against Antiochos III (208–206 BC).

In our opinion, the tetradrachm series could have been minted

around the same time as Group I or, perhaps more likely, shortly

after it.

The monograms

This proposed dating is further

strengthened by the monograms. The significance of the monograms

on Bactrian coins is still debated – while they could be

representative of the officials responsible for the minting[16],

it is also plausible to interpet them as mint marks.

All known specimens of the unusual tetradrachm series

have the monogram

![]() ,

accompanied by ΔΙ (fig.

1) or

,

accompanied by ΔΙ (fig.

1) or

(fig.

2).

![]() is,

to our knowledge, not attested elswhere. It resembles the

monogram

is,

to our knowledge, not attested elswhere. It resembles the

monogram

from

the gold and silver coins of Antiochos I and II, which Brian

Kritt attributes to Aï Khanoum[17].

appears

on other tetradrachms of Euthydemos I (Bordeaux Group B5),

accompanied by the letters

or

TI[18].

The first combination is of particular importance since

the additional letters are the same that form

![]() –

in the monogram they are placed on top of, not next to each

other. It therefore seems possible that

–

in the monogram they are placed on top of, not next to each

other. It therefore seems possible that

![]() evolved

from the letters on the Group B5 tetradrachm rather than the

Seleukid monogram from Aï Khanoum. ΔΙ is

also found on Bactrian gold staters and tetradrachms of

Antiochos I[19],

but more important is its appearance on a bronze series of

Euthydemos I (Bordeaux Group N1; fig. 8). These coins

have even more in common with the unusual tetradrachms: Both

have the monograms placed in the exergue, which is only rarely

the case in the coinage of Euthydemos I[20],

and they share a pelleted border on the obverse as well as the

reverse. The bronzes with the ΔΙ monogram

can be precisely dated: The two known examples are marked with a

Seleukid anchor, which was applied in the immediate aftermath of

the war with Antiochos III, i.e. in 206 BC[21].

The above described similarities make it plausible that the

unusal tetradrachm series was minted prior to the ΔΙ bronze

coins in the same mint (or under the same minting official).

evolved

from the letters on the Group B5 tetradrachm rather than the

Seleukid monogram from Aï Khanoum. ΔΙ is

also found on Bactrian gold staters and tetradrachms of

Antiochos I[19],

but more important is its appearance on a bronze series of

Euthydemos I (Bordeaux Group N1; fig. 8). These coins

have even more in common with the unusual tetradrachms: Both

have the monograms placed in the exergue, which is only rarely

the case in the coinage of Euthydemos I[20],

and they share a pelleted border on the obverse as well as the

reverse. The bronzes with the ΔΙ monogram

can be precisely dated: The two known examples are marked with a

Seleukid anchor, which was applied in the immediate aftermath of

the war with Antiochos III, i.e. in 206 BC[21].

The above described similarities make it plausible that the

unusal tetradrachm series was minted prior to the ΔΙ bronze

coins in the same mint (or under the same minting official).

An experiment in times of war?

With all this taken into account, the

tetradrachm series seems to have been created between 210 and

206 BC. If this dating is accepted, there could be a connection

to the war against Antiochos III: The Seleukid monarch invaded

Bactria in 208 BC in order to reintegrate it into his Empire,

but this plan failed since he was unable to capture Euthydemos’

capital. After a two-year siege of Baktra, Antiochos III had to

agree to a peace treaty. He accepted the kingship of his

adversary and even promised to marry one of his daughters to

Euthydemos’ son Demetrios I[22].

The gold octadrachm (Group J1) was likely struck on this

occasion[23].

If the unusal tetradrachms were minted during the conflict, this

might give an explanation for their iconography: In times of war

it was possibly considered necessary to address the users of the

coins more directly – this could have been attempted by turning

Herakles’ head from his usual profile to a frontal position.

This change must have been immediately noticeable to the ancient

viewer and by glancing at Herakles looking directly at them,

they could have felt a stronger connection to the hero and the

royal dynasty he embodied. In any case, the tetradrachm series

is best understood as an experimental issue intended to test

changes to the established iconography of the reverse.

Ultimately, however, Herakles’ frontal glance did not find

enough approval and was therefore not adopted for the following

silver coinage of Euthydemos I.

Picture Credits:

Fig. 1: Collection of Klaus Grigo (photograph by Gorny

& Mosch); fig. 2:

Classical Numismatic Group, Mail Bid Sale 75,

23.05.2007, lot 619; fig. 3–7: Collection

of Klaus Grigo (photograph Robert Dylka); fig. 8:

Bibliothèque nationale de France, no. 1970.604.

[2] Polybios 10,49;

11,34.

[3] An overview of the

history of the successors of Euthydemos I is given by

Wünsch 2022, pp. 296–305.

[4]

SC I, no. 318. Polybios 11,34,1 states

that Euthydemos was a native of Magnesia, but gives no

further details. On the basis of the Seleukid

tetradrachms, Newell 1941, p. 275 assumes that

Euthydemos I hailed from Magnesia on the Sipylos. This

matter is, however, still disputed as Bernard 1985, pp.

131–133 argues for Magnesia on the Meander as

Euthydemos’ hometown, while Lerner 1999, p. 54 considers

Magnesia in Thessaly.

[5] The tetradrachm

sold by Classical Numismatic Group was part of the

Kuliab hoard and has been published by Bopearachchi

1999, p. 41 no. 61.

[6] Bopearachchi 1991,

p. 163 Series 25; SNG ANS, no. 180.

[7] Bordeaux 2018, p.

104. The monograms appear on two tetradrachm series, on

which Eukratides I wears the Boeotian helmet adorned

with bull’s horn and ear (minted after his Indian

campaign of 163/62 BC): Bopearachchi 1991, pp. 203–205

Series 6C (ΔΙ),

6Q ().

[8] Bordeaux 2018, p.

104.

[9] Bopearachchi 1991,

p. 152

Series 12,

Series 13, and

Series 14 = Holt 1999, pp.

165–167 Series H.

[10] Bopearachchi

1991, pp. 196 f.

Series 1. For the dating of

Antimachos II see Wünsch 2021, p. 126.

[11] Bopearachchi

1991, pp. 199–214

Series 1;

Series 2;

Series 4;

Series 5;

Series 6;

Series 7;

Series 8;

Series 11;

Series 12;

Series 19;

Series 20.

[12] Glenn 2020, pp.

323–325, 337 f.

[13] Bordeaux 2018, p.

103; Glenn 2020, pp. 140–143.

[15] Senior 2001,

Types 59, 69, 83.

[16] Bordeaux 2018,

pp. 137–139; Glenn 2020, pp. 173–178.

[17] Kritt 2016, p.

106 no. 21 (stater of Antiochos I), pp. 149–153 (staters

and drachms of Antiochos II).

[18] Bordeaux 2018, p.

178 no. 154 (),

p. 178 nos. 155–157 (TI).

is

furthermore present on the silver coinage of Euthydemos

II (Bopearachchi 1991, p. 168

Series 4C), Eukratides I (Bopearachchi 1991, p. 205

Series 6Q), Demetrios II (Bopearachchi 1991, p. 195

Series 1F,

Series 1G,

Series 2A) and Heliokles I (Bopearachchi 1991, p.

223

Series 1M, p. 224

Series 2F).

[19] Kritt 2016, p.

102 nos. 2–3, p. 108 no. 10.

[20] Apart from the

bronzes, the monograms are placed in the exergue only on

the silver coins of Bordeaux Groups B5, C2, F2/4.

[21] Dumke 2017 argues

that the anchor mark could have been applied to make the

bronzes an acceptable currency for the Seleukid

soldiers, after their king had concluded peace with

Euthydemos I. Interestingly, ΔΙ also

appears on tetradrachms of Antiochos III and Seleukos IV

(SC

I, nos. 1109–1113 [»ΔI Mint«]; SC II,

nos.

1326,

1327,

1328, and

1329 [»Formerly the ΔI Mint«]): As

their production began c. 202 BC, the usage of the

monogram was possibly inspired by the Bactrian bronze

coins.

[22] Wünsch 2022, pp.

293–296.

[23] Bordeaux 2018,

pp. 108 f.