Copies of Ancient Coins and Inventions all’antica in the Work of Jacopo Strada*

In memory of my friend and colleague Michael Matzke

Zusammenfassung: Jacopo Strada

betont in seinem Werk Epitome Thesauri antiquitatum (Lyon

1553), dass man »die Münzen gut kennen müsse, um

echte von zeitgenössischen Nachahmungen zu unterscheiden«

(i.e. die Paduaner). Dies gelingt ihm selbst aber auch nicht

immer. So finden sich in seinem Münzcorpus mit über 8.000

Münzen, dem Magnum ac Novum Opus (MaNO),

zahlreiche Nachahmungen antiker Münzen aus dem 16. Jahrhundert.

Diese finden sich aber nicht nur im Werk

Stradas, sondern ebenfalls in den Werken anderer

zeitgenössischer Antiquare, wie Enea Vico, Pirro Ligorio und

Hubertus Goltzius. Darüber hinaus schafft Strada auch ›neue‹

Münzen, die er in seinem Münzcorpus abbildet und denen er durch

seine Münzbeschreibungen in der Diaskeué eine

vermeintlich gesicherte Authentizität verschafft.

In dem Beitrag werden einige dieser ›neuen‹

Münzen und Paduaner vorgestellt, zugrundeliegende Quellen

aufgezeigt und ihre Rezeption durch Zeitgenossen dokumentiert.

Dadurch ergeben sich neue Einblicke in die Arbeits- und

Vorgehensweise renaissancezeitlicher Antiquare.

Schlagwörter: Jacopo Strada

http://d-nb.info/gnd/118834320, Giovanni da Cavino

http://d-nb.info/gnd/122755413, Geschichte der Numismatik,

Nachahmungen von Münzen, Antiquare der Renaissance.

Abstract:

In his work Epitome Thesauri antiquitatum (Lyon 1553),

Strada emphasised the importance of thorough numismatic

knowledge to distinguish original coins from modern imitations

(i.e. ›Paduans‹). Nonetheless, he was often mistaken and his

corpus of over 8,000 coins, the Magnum ac Novum Opus (MaNO),

includes numerous sixteenth-century imitations of ancient coins.

These imitations were

also depicted in the works of his contemporaries, e.g. the

antiquarians Enea Vico, Pirro Ligorio and Hubertus Goltzius.

Strada also created ›new‹ coins illustrated in the MaNO and

seemingly authenticated by descriptions in the Diaskeué.

My contribution presents

a number of ›new‹ coins and Paduans together with essential

source material and their reception by Strada’s contemporaries.

Thereby, in-depth insight into methodology and approach of

Renaissance antiquarians is provided.

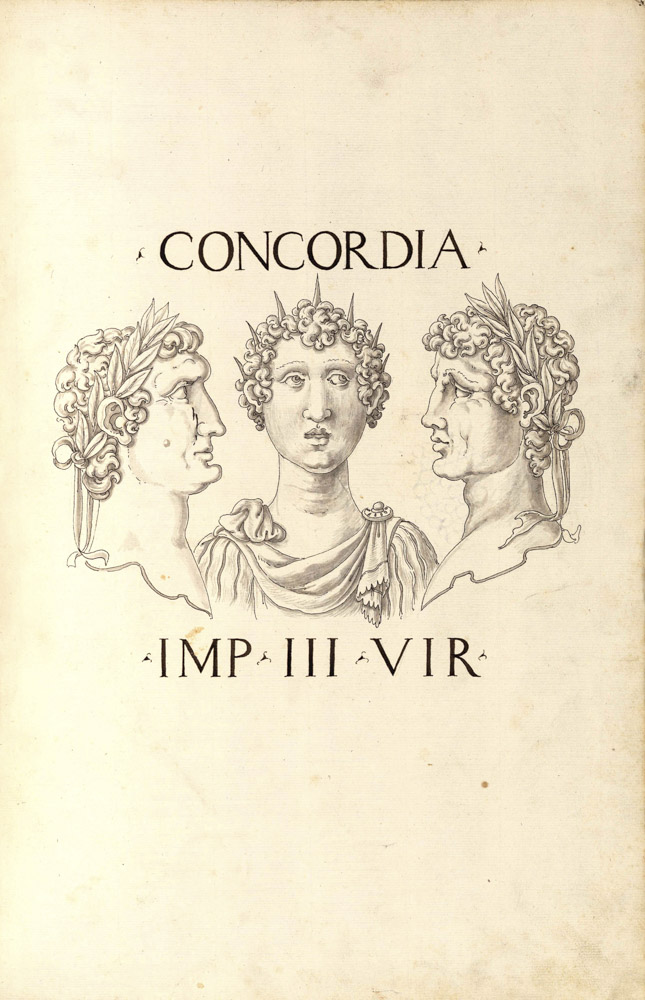

Jacopo Strada (fig. 1)

was born in Mantua (b. 1505‒1515, d. 1588 in Vienna) as the son

of aristocratic parents[1].

In Mantua, he was trained as goldsmith and painter and belonged

to the circle of Giulio Romano[2].

His main interest lay in the field of ancient numismatics[3].

Giulio Romano owned a considerable coin collection stored in his

house in Mantua which Strada frequently visited[4].

Back in the 1530s, Strada sought to contact Roman antiquarians

and collectors. Even then, he started to document inscriptions

and coins.

By the 1540s, Strada

must have had acquired a certain renown as an expert in

antiquities, since from 1544 he worked as antiquarian for Johann

Jakob Fugger (1516‒1575). In 1546, he temporarily settled in

Nuremberg, working as painter and goldsmith. During this period,

he started to collect material for his future numismatic

writings. Fugger sponsored his studies by granting him funds for

his journeys to France and Italy, where he visited coin

collections and exchanged ideas with fellow antiquarians. In

1553, before leaving for Rome to spend two years as Fugger’s

antiquities’ scout, he published in Lyon the only printed book

he ever authored.

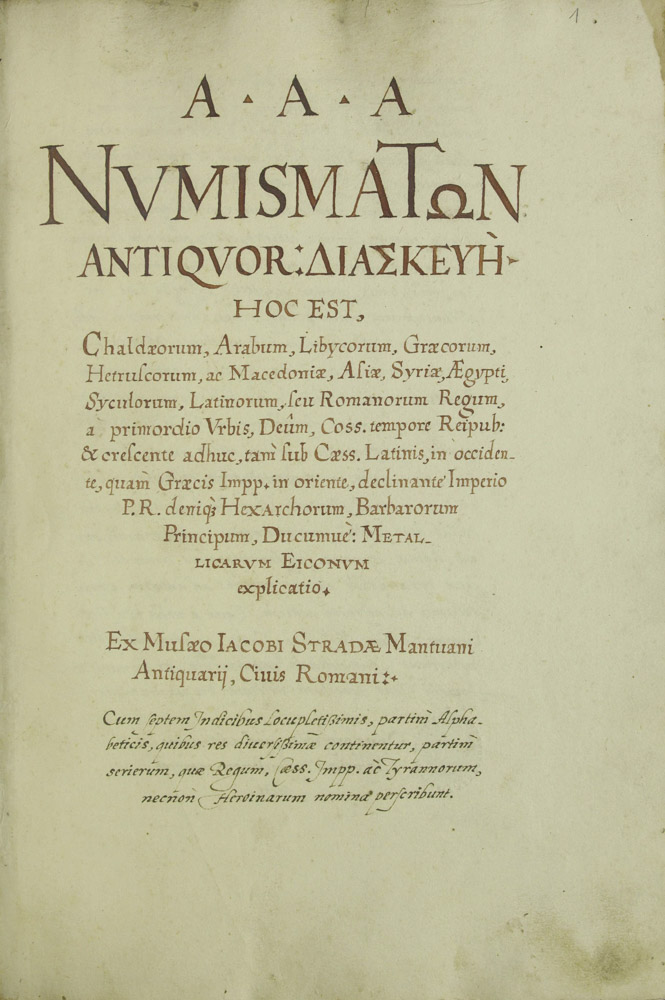

This book was the

Epitome Thesauri Antiquitatum, hoc

est Impp. Rom. Orientalium et

Occidentalium Iconum, ex antiquis Numismatibus quàm fidelißimè

deliniatarum. Ex Musaeo Iacobi de

Strada Mantuani Antiquarij (Epitome)

(fig. 2)[5].

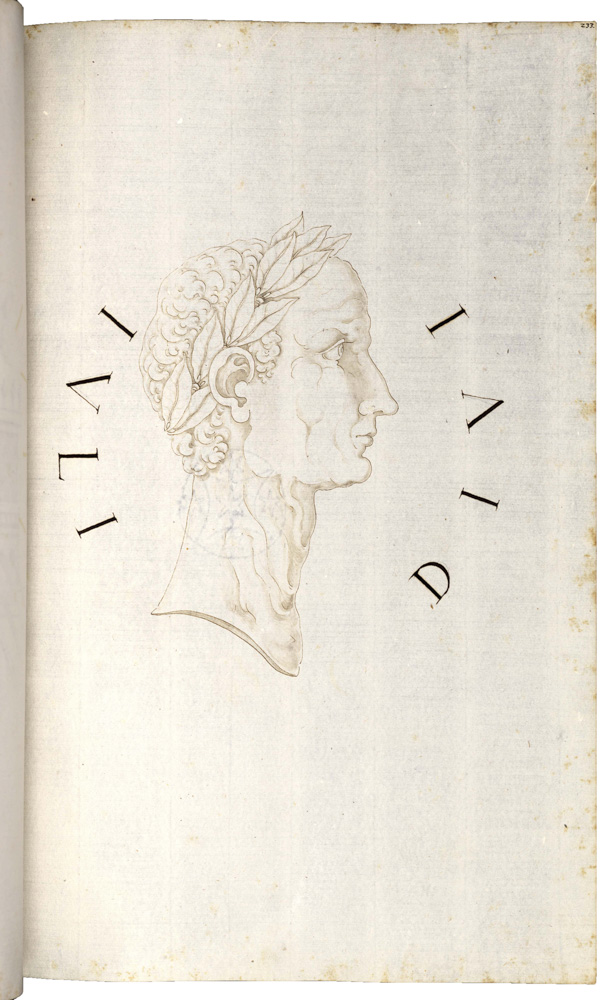

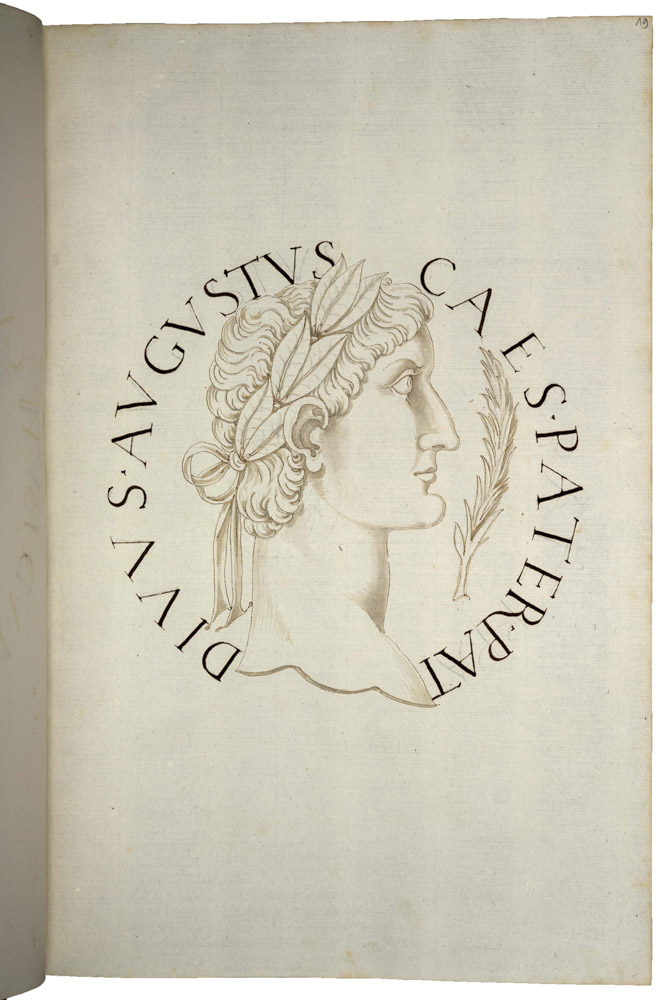

The Epitome is a book of biographies enriched with

portraits of the Roman emperors from Julius Caesar to Charles V,

including their relatives (fig. 3)[6].

In addition, the

Epitome contains short descriptions of several coin reverses[7].

These reverses remained without illustrations, since the

conversion into woodcuts would have required a considerable

amount of time and technical effort[8].

Strada took many of these reverse motifs[9]

from the illustrations of his MAGNUM AC NOVUM OPUS Continens

descriptionem Vitae imaginum, numismatum omnium tam Orientalium

quam Occidentalium Imperatorum ac Tyrannorum, cum collegis

coniugibus liberisque suis, usque ad Carolu(m) V. Imperatorem.

A Iacobo de Strada Mantuano

elaboratum. TOMUS PRIMUS. ANNO DOMINI MDL

(MaNO) (fig. 4)[10].

This thirty-volume work is the

subject of our research project at the Forschungszentrum Gotha[11].

The descriptions in the

Epitome are so precise that the coins and contorniates

mentioned can be identified[12].

Strada was the first to publish descriptions of coin reverses

and thus made a considerable contribution to sixteenth-century

numismatic research[13].

In addition, his comments provide information on many aspects of

numismatics and antiquarian research: i.e. religion, ceremonies,

architecture and Roman society. Strada’s research on ancient

monuments was based on the concept of the division of

antiquitates into sacrae, publicae,

privatae and militares as established by Marcus

Terentius Varro[14].

In the preface of the Epitome he wrote about the

importance of in-depth knowledge of the coins to be able to

distinguish genuine exemplars from contemporary

imitations/fantasies[15].

He said that, in his days, coins existed that were made by

»engravers who are as brilliant as they are excellent, [so] that

they are comparable to the ancients, and who are too well-known

to be named here. Therefore, one must take the greatest care to

select the coins which have just been made in bas-relief by the

[masters] who are particularly experienced, for their beauty and

elegance«[16].

The names of these engravers can be found

in Enea Vico’s Discorsi sopra le medaglie[17]:

Giovanni da Cavino and his son; Vettore Gambello, Benvenuto

Cellini, Alessandro Cesati called Greco, Leone Leoni from

Arezzo, Iacopo da Trezzo and Federico Bonzagna from Parma.

At the time, Federico Bonzagna was

considered the most talented of these modern engravers[18].

Nonetheless, as will be

shown below, even Strada did not always succeed in

distinguishing modern creations from original ancient coins. He

was also not averse to inventing coin motifs that he then

included in his numismatic works. Here, I present three examples

of illustrations from volumes 1 to 14 of the MaNO[19].

Strada’s Creative

Numismatics

The first example is a

rather visually expressive coin, depicting the murder of Cicero.

It is described in the Epitome, in which only its obverse

is illustrated (fig. 5). Obverse and reverse are shown on a

drawing in the MaNO (figs 6a and b)[20]

and described in the A<ureorum> A<rgenteorum> A<ereorum>

NumismatΩn Antiquorum: ΔΙАΣKEYH. Hoc est, Chaldaeorum,

Arabum, Libycorum, Græcorum, Hetruscorum, ac Macedoniæ, Asiæ,

Syriae, Ægypti, Syculorum, Latinorum, seu Romanorum Regum, a

primordio Vrbis, Deûm, Coss. tempore Reipub: & crescente adhuc,

tam sub Cæss. Latinis, in occidente, quam Græcis Impp. in

oriente, declinante Imperio P.R. denique Hexarchorum, Barbarorum

Principum, Ducumuè: METALLICARUM EICONUM explicatio. Ex Musæo

IACOBI STRADÆ Mantuani Antiquarij, Civis Romani: Cum septem

Indicibus Locupletissimis, partim Alphabeticis, quibus res

diuersissimæ continentur, partim serierum, quæ Regum, Cæss.

Impp. ac Tyrannorum, necnon Heroinarum nomina perscribunt

(Diaskeué) (fig. 7)[21].

This eleven-volume manuscript of coin descriptions is a further

subject of our research project. Strada states in the

Diaskeué that he saw this bronze coin at Giulio Romano's

house in Mantua[22],

while in the Epitome he mentions Rome as the coin’s home[23],

Unfortunately, no original coin model could be determined for

the two drawings[24].

Strada used here a literary source as

basis for the coin drawing, i. e. a

reference to Livy. He described the proscriptions under the

triumvirate of Octavian, Lepidus and Antonius, the aim of which

it was to avenge Caesar, and named the most famous victims[25].

Their portraits are depicted on the obverse of the coin. The

reverse of an aureus minted for Septimius Severus might have

been used as model (figs 8a and b). There, Julia Domna is

depicted between Caracalla and Geta[26].

Fig. 5: Coin with the triumviri, Epitome, p. 11 (HAB Wolfenbüttel)

Fig. 7: Frontispiece of the Diaskeué 1 (UB Wien)

Sometimes it is assumed

that this dramatic scene (fig. 9) was based on models used in

the paintings of the great decorative programmes of the time.

Nonetheless, no corresponding models could be identified in the

work of Giulio Romano[27]

or in Rome[28].

Only for some individual motifs potential models could be

discerned, as happened, for example, for the presentation of

Cicero’s head by the legionary Laena. Such scenes exist on the

Column of Trajan[29],

of which Strada probably made a copy (fig. 10)[30].

The trial scene, composed like a stage set, might instead have

been modelled on miniature drawings by Giorgio Giulio Clovio

(1498‒1578)[31],

for example on the book illuminations entitled The Conversion

of Proconsul Sergius (fig. 11) and Faith, Love, Hope

(fig. 12). Since none of Strada’s contemporaries illustrated

this coin, i.e. neither Enea Vico, Hubertus Goltzius, Sebastiano

Erizzo nor Pirro Ligorio, it is safe to assume that it was

Strada’s own invention.

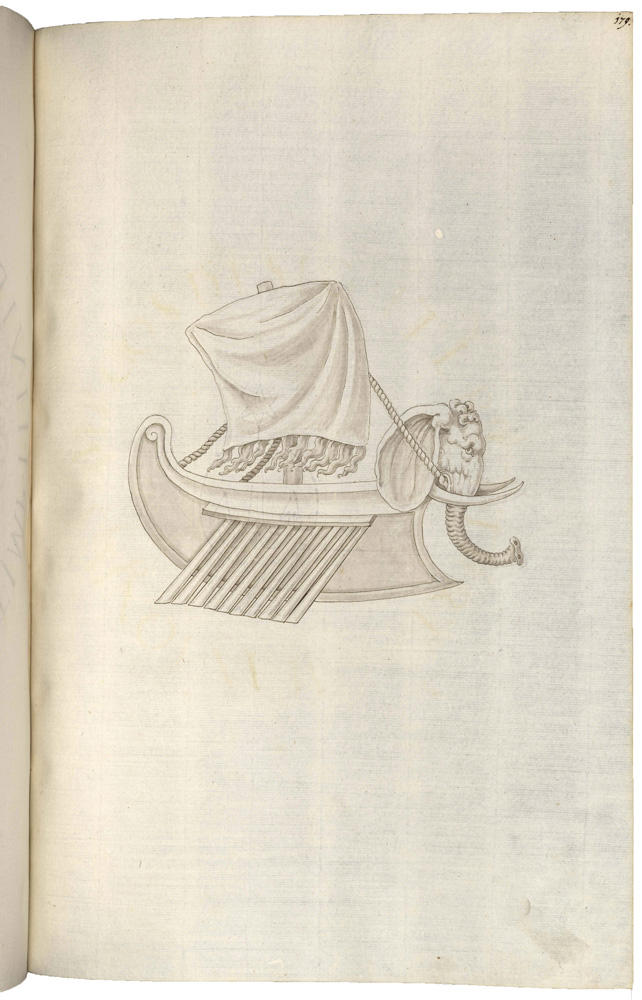

Another one of Strada’s

very creative and peculiar inventions is a ship with a prora

in the shape of an elephant’s head (figs 13a and b)[32].

It can be found in the third volume of the MaNO which is

dedicated to the coins of Marcus Antonius. Unfortunately, there

is no description in the Diaskeué nor could an exact

ancient model be identified[33].

What led Strada to this invention – perhaps meant as an allusion

to Cleopatra and the lost Egyptian fleet[34]

or simply the misinterpretation of a coin image – must remain

without answer.

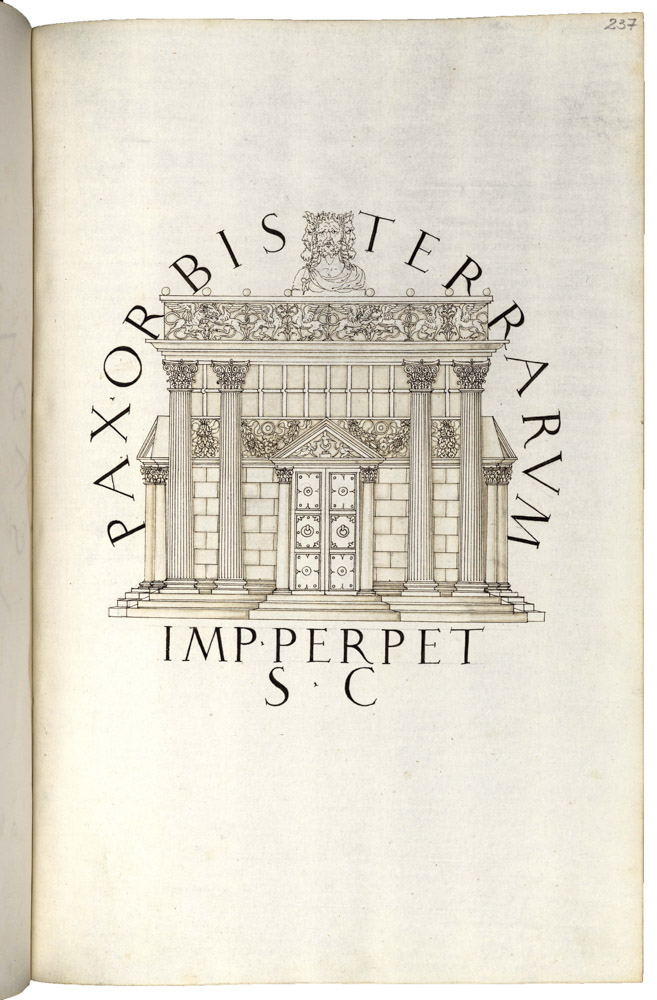

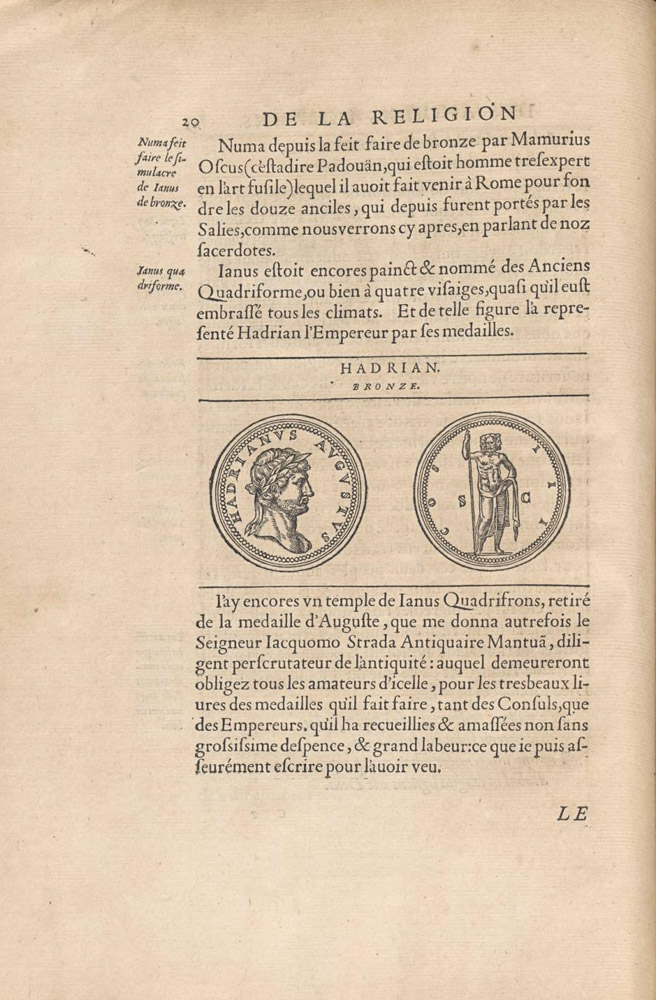

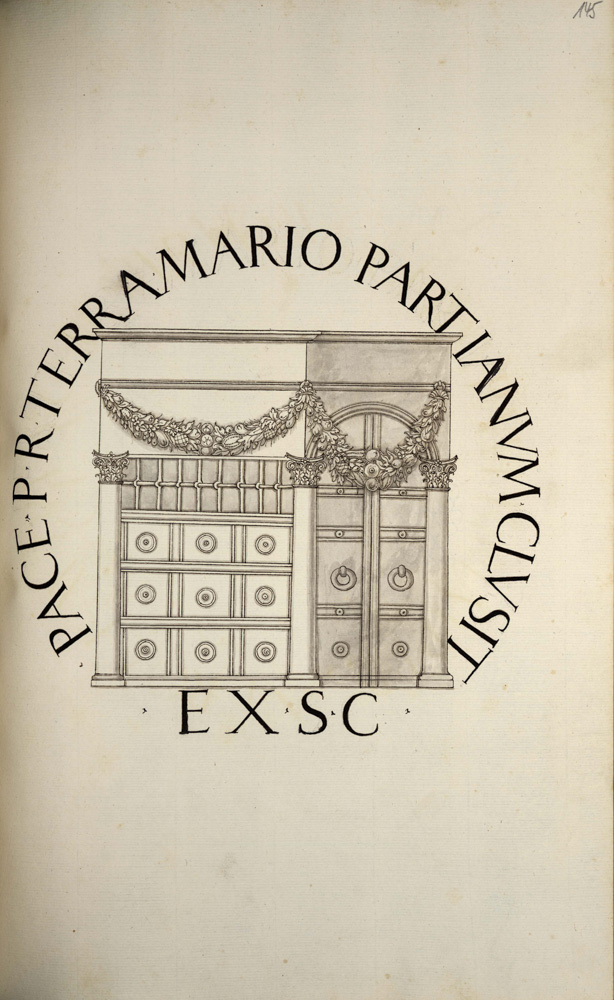

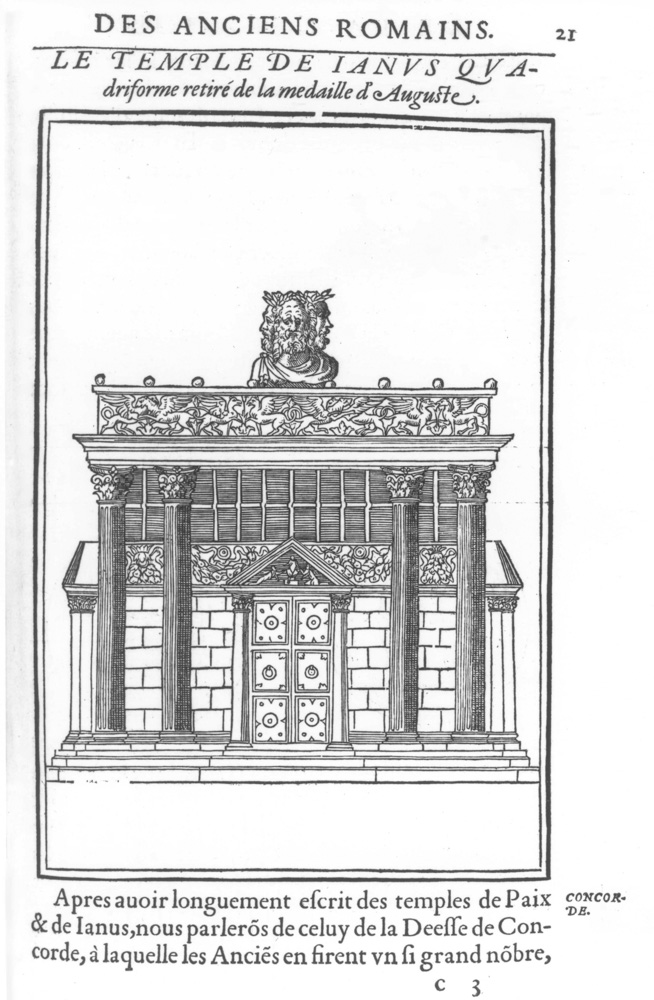

The third coin offers

Strada’s most interesting invention, accepted until the

nineteenth century. It is a denarius with Augustus radiate but

no legend on the obverse. On the reverse (fig. 14), the temple

of Janus Quadrifrons is shown with the inscription PAX ORBIS

TERRARVM IMP. PERPET. S. C. This coin is said to have been in

Strada’s own coin collection.

No such ancient coin

ever existed. The model for this invention was probably a

sesterce of Hadrian, also depicted by Du Choul in his work

Discours della religion des ancien Romains, on which Janus

is depicted with three faces (fig. 15)[35],

although normally he is only shown with two. For the temple

building, Strada borrowed parts of the illustration of the

Temple of Janus on coins of Nero which he also depicted in the

MaNO (fig. 16)[36],

e.g. the gate of the temple and the construction of the roof.

Furthermore, the coin legend itself is an invention. It actually

either refers to Christ or to an ideal Christian ruler[37],

since for the motif on the coin obverse – showing Augustus

radiate, and therefore deified, as described in the Diaskeué

– a ›divus‹ legend would normally be expected[38].

Du Choul was Strada’s only contemporary who illustrated this

representation of the temple (fig. 17)[39]

which, as he states, he had received from Strada (see

fig.

15). Du Choul's work was later adopted by

Louis XIV’s and Napoleon I’s coin engravers to commemorate

successful peace treaties, i.e. the Peace of

Rastatt in 1714 (figs 18a and b)[40]

and the Peace of Pressburg (today Bratislava) of 1805 (figs 19a

and b)[41].

When the peace treaty of Pressburg,

negotiated by Francis I of Austria, was broken in 1809 and the

French army remained victorious, Napoleon issued a coin with the

motif of the Janus Temple. In this case, the temple was not

shown with open doors, as had been customary in ancient Rome in

times of war, but with broken doors (figs 20a and b) meant to

indicate a particularly violent breach of peace[42].

In particular, the third

example shows how much iconographic and numismatic knowledge

Strada was able to use for his inventions. Therefore, he managed

to design details that could not be found on ancient originals

in such a way that they seemed authentic to his contemporaries

(e.g. Du Choul).

Therefore, in the

following section, selected exemplars of coin drawings from the

first 14 volumes of Strada’s MaNO will be presented.

These drawings were based on inventions by contemporary

engravers who also used their talents to design coins after the

antique that owed more to their imagination than to ancient

originals.

Creations by Cavino and

his Contemporaries

To identify Cavino’s and

his contemporaries’ inventions solely by the use of

drawings is very difficult. There only remains an identification

based on inaccuracies in their presentation or on mistakes in

the coin legends. An identification becomes impossible, if the

model for the copy is an authentic coin and if the copy matches

it. In this case, only the careful study of its condition, of

the material and of the edges makes it possible to recognise

whether it is a Paduan.

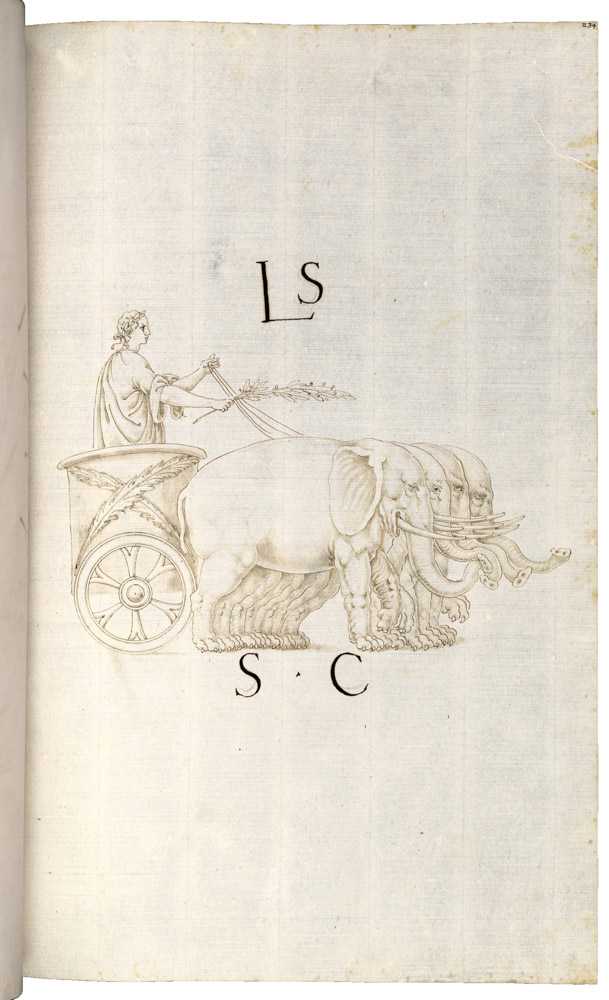

Inventions without

direct ancient models can be found in the first volume of the

MaNO, for example in the case of »Caesar on the Elephant

Quadriga« (figs 21a and b)[43].

Strada claimed to have seen this coin in the collection of

Antonio Agustín[44].

This claim can however not be confirmed, since Agustín’s

collection was looted and dispersed by Napoleonic troops in the

early nineteenth century[45].

There is no matching illustration in his Dialoghi intorno

alle medaglie etc. Rather, the coin seems to have been

Cavino’s invention (figs 22a and b) and is not depicted by other

antiquarians[46].

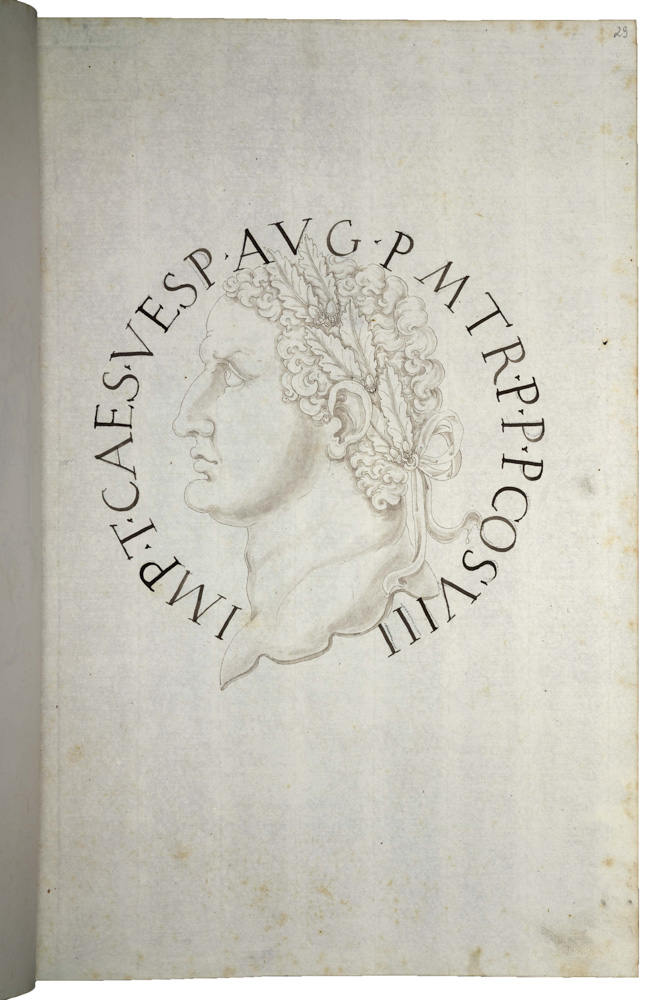

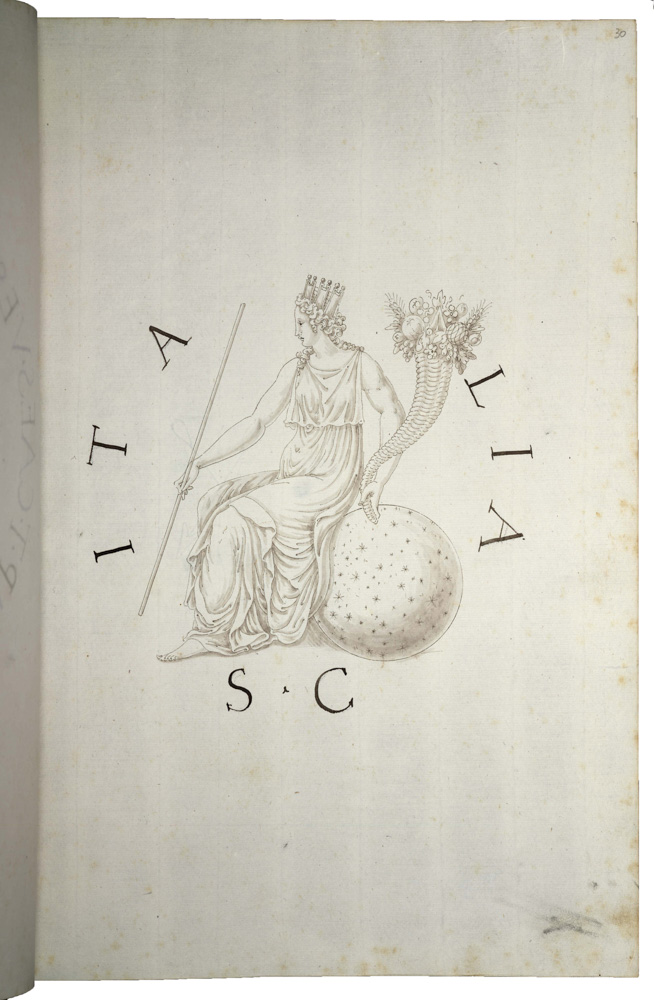

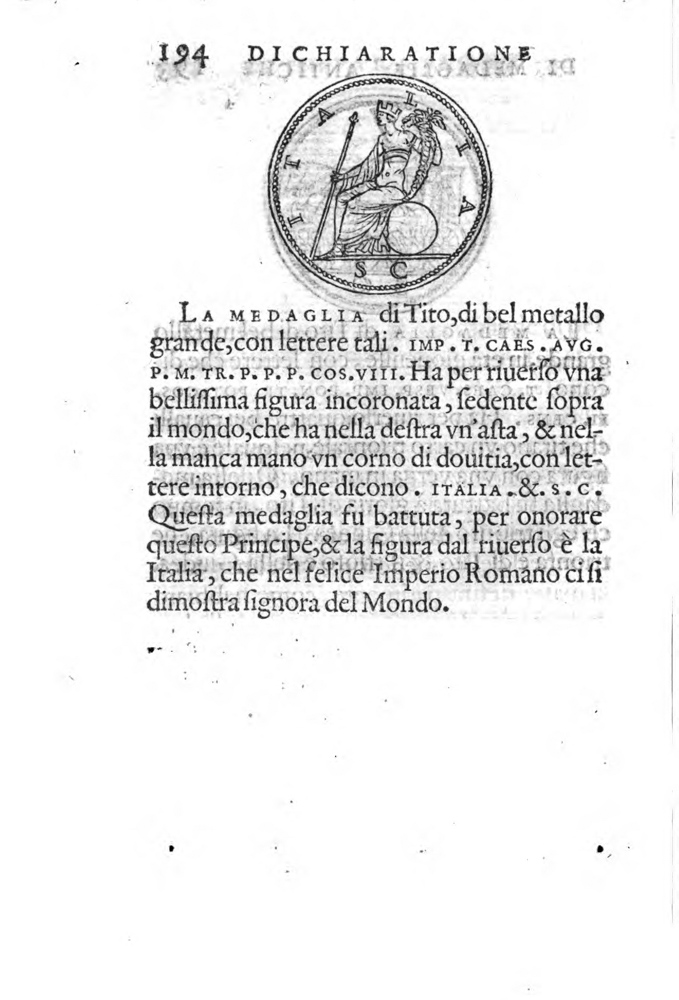

Volume 12 of the MaNO

shows a coin with Titus, laureate and looking to the left, on

the obverse and an Italia with mural crown sitting on a globe on

the reverse (figs 23a and b)[47].

Unfortunately, there is no description in the Diaskeué;

therefore we do not know, in which collection Strada saw this

coin. Its provenance would be of particular interest, since

Klawans assumes that the coin is a modern forgery[48].

While the illustration in the MaNO proves its existence

in the sixteenth century, only Sebastian Erizzo included its

depiction in his Discorso sopra le medaglie antiche etc.

(fig. 24)[49],

in which it is shown with the same reverse legend ITALIA S C.

A further invention by

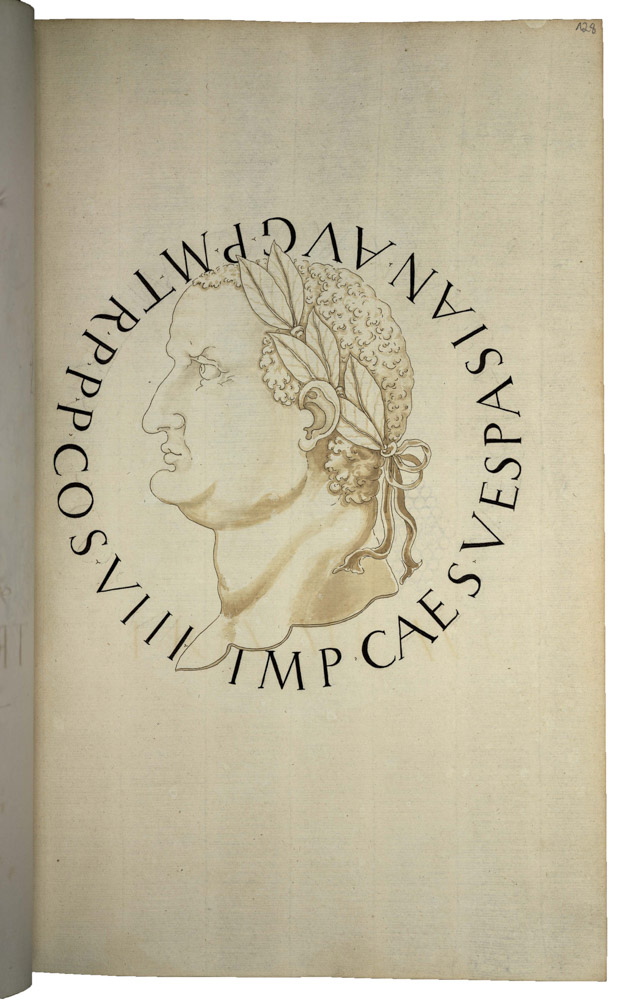

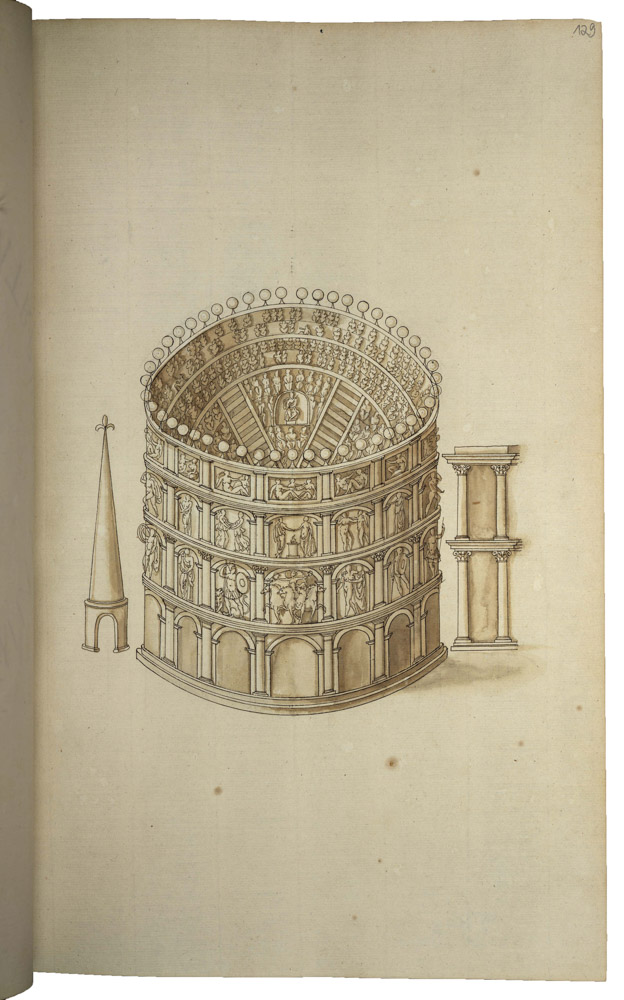

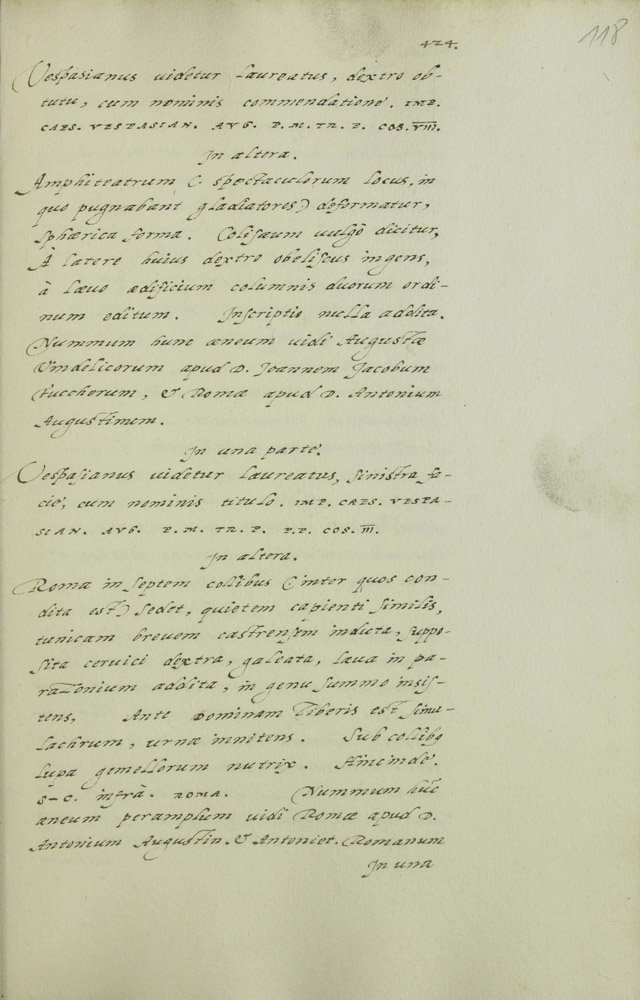

Cavino without any direct ancient model is a coin with Vespasian

on the obverse and the Colosseum and the Meta Sudans on the

reverse (figs 25a and b)[50].

He claimed to have seen it in Fugger’s as well as Agustín’s

collections. Here, Cavino combined the obverses and reverses of

several ancient models (obverse of the sesterce of Vespasian

with the reverse of a sesterce of Domitian for his deified

brother Titus (figs 26a and b)[51].

Strada described Vespasian on the obverse as »looking to the

right« (fig. 27); in the same way he is also shown on the –

probably – original Paduan. There, the legend COS VII

substitutes the inscription of COS VIII included in both drawing

and description. Nonetheless, Strada presented Vespasian as

»looking to the left«, identical to another Paduan based on a

sesterce of Titus (figs 28a and b)[52].

Apart from Strada, no other antiquarian reproduced this coin.

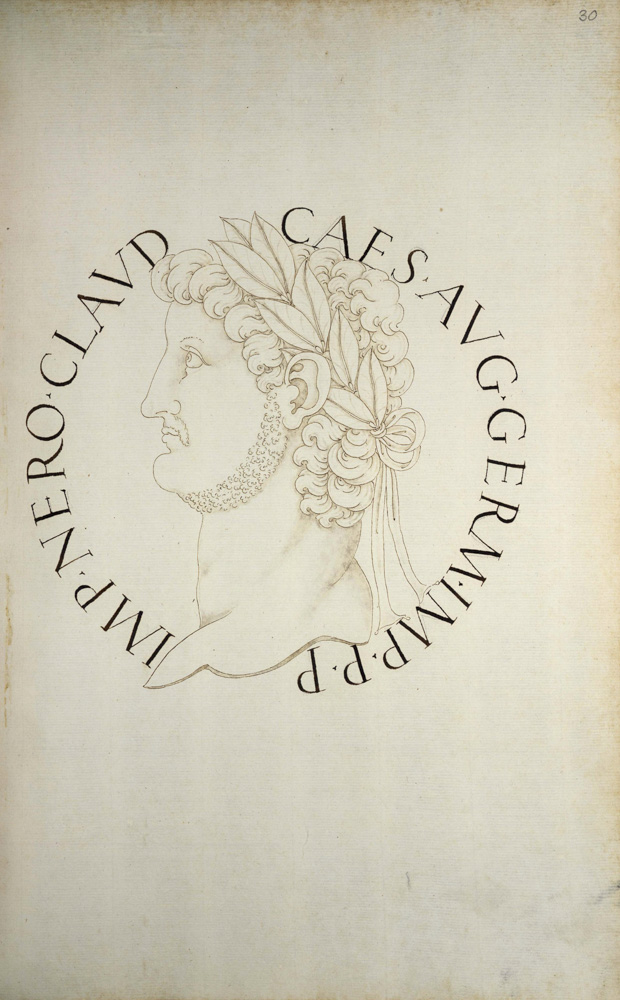

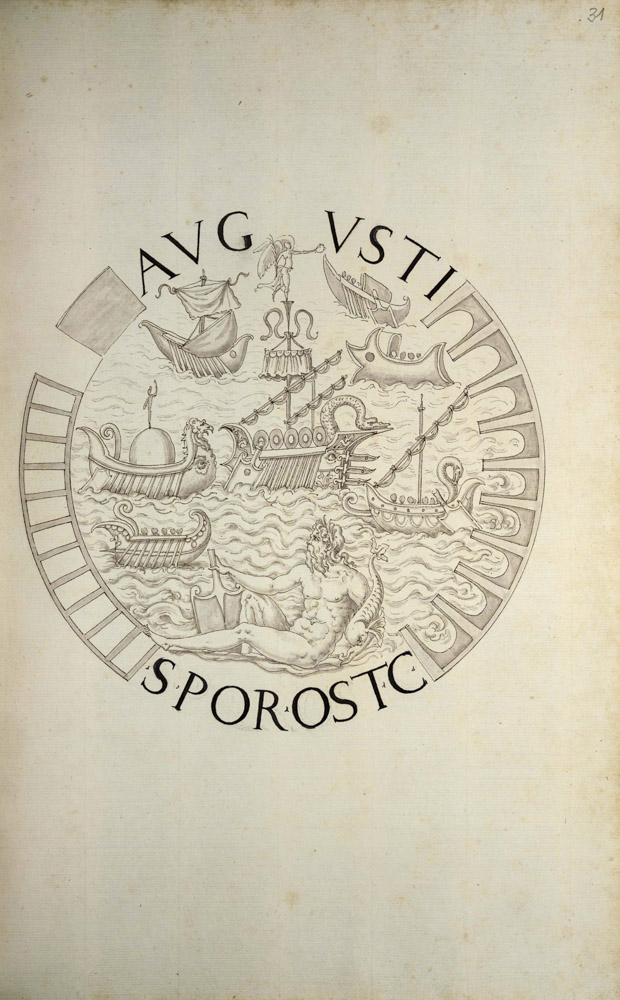

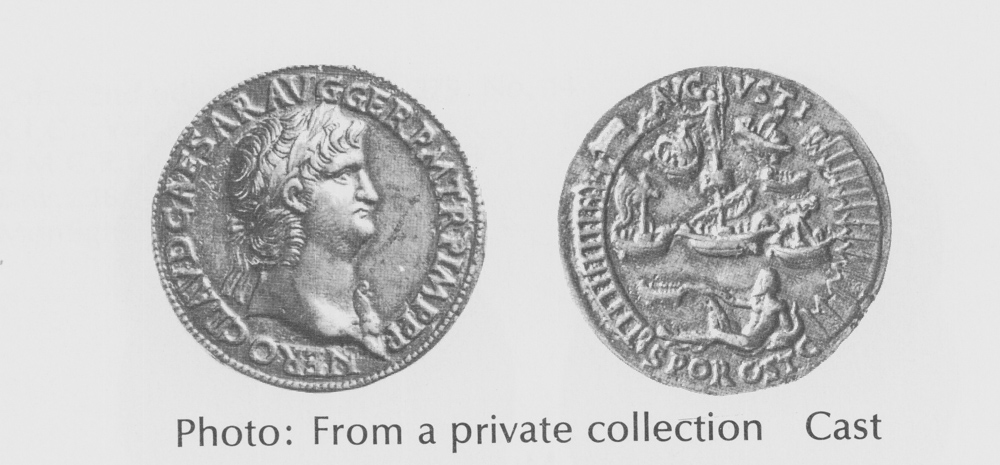

Cavino’s imitation of

Nero’s Porta-Ostiensis coin is also found in the ninth volume of

the MaNO (figs 29a and b)[53].

The fact that this coin was an imitation created by Cavino is

evident by the row of shields on the ship in the coin’s centre

(fig. 30) which can only be found on this imitation. In the

Diaskeué, Strada claimed to have this piece in his own

collection[54].

His contemporaries however reproduced the ancient original[55].

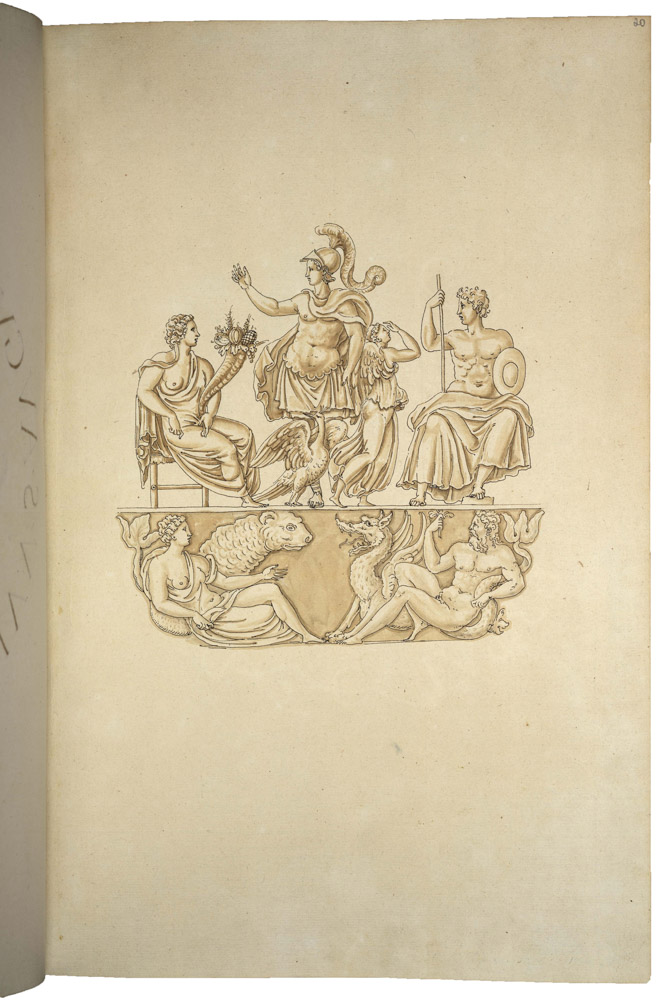

Another Paduan shows

»Augustus among the Gods« (figs 31a and b)[56].

Strada depicted Augustus with a shield in his left hand and a

sceptre in his right in addition to Terra with a sea monster and

Oceanus with a dragon-like monster as shown on the imitation by

Cavino (figs 32a and b)[57].

On the contorniate, dating to the fourth century AD

(figs

33a and b)[58],

which probably served as model, Augustus holds a globe in his

left hand and a spear in his right; Victoria holds a wreath in

her raised right hand; a bovine is placed behind Terra and next

to her appears a blossoming plant. A dolphin-like sea monster

stands before Oceanus with crab claws stuck in his hair, while a

water plant can be seen behind his back. Vico and Ligorio

(figs

34a and b) also depicted this Paduan, whereas Goltzius shows the

original (fig. 34c)[59].

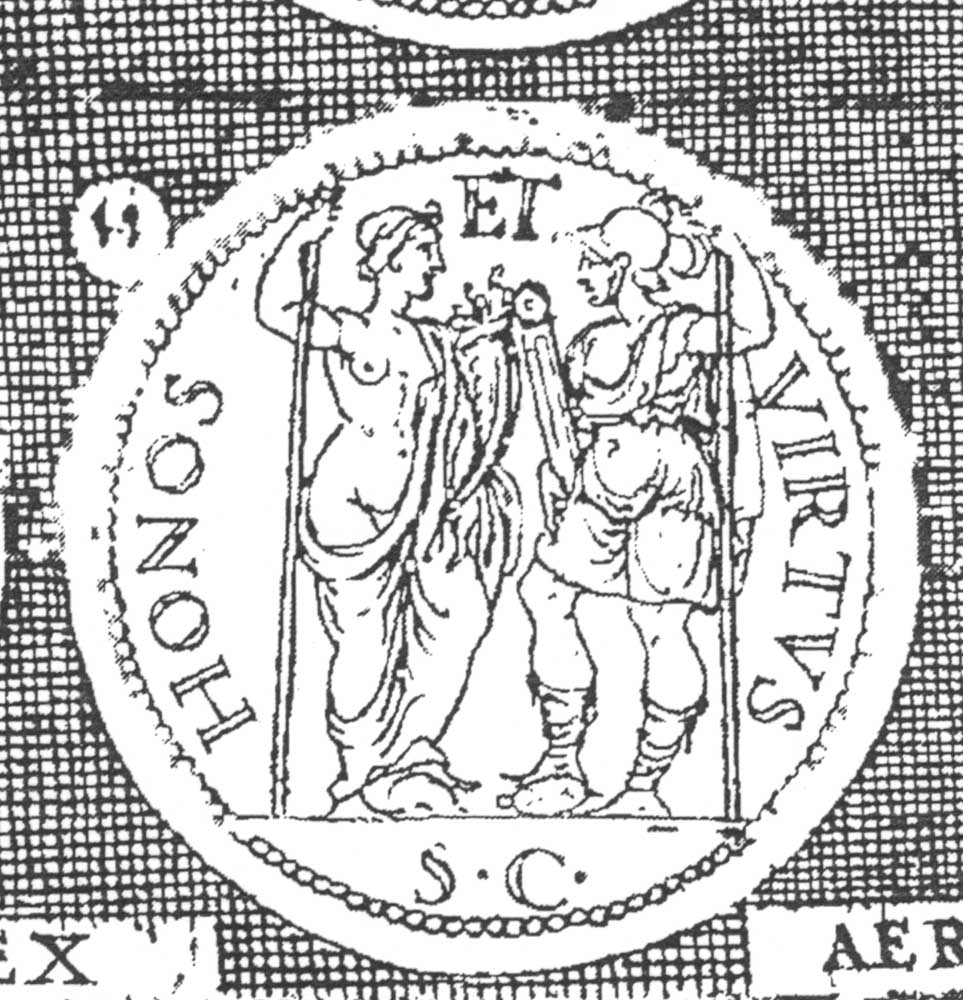

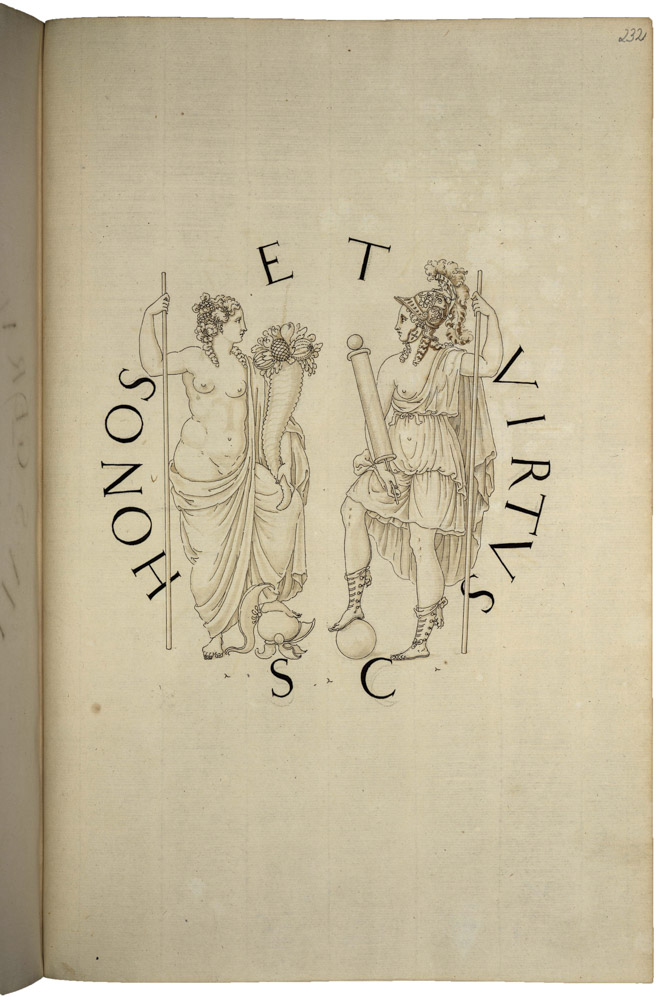

For the final piece to

be discussed here, Strada described the ancient originals in the

Diaskeué in detail, while presenting a new, previously

unknown version in the MaNO. The coin’s ancient original

shows ›Honos‹ (to the left) and ›Virtus‹ (to the right)

looking at each other (figs 35a, b and c). ›Honos‹ holds a

cornucopia in his left hand and a sceptre in his right; ›Virtus‹

wears a helmet and military attire, the parazonium is in her

right hand and a lance in her left. Her right foot rests on a

helmet and the legend reads: HONOS ET VIRTVS S C[60].

The coin image is described in the Diaskeue in the same

way[61].

Strada mentions Antonio Agustín as the owner, whose collection –

as mentioned above – was looted and dispersed by Napoleonic

troops in the early nineteenth century. In Agustín’s original

edition Dialogos de medallas inscriciones etc.,

this coin was depicted exactly as described by Strada, i.e.

identically to the ancient original[62].

Ligorio as well depicted it in this fashion[63].

On Cavino's imitation (fig. 35b)[64],

however, Honos places his right foot on a dolphin and Virtus her

right foot on a turtle. Vico also reproduced the coin in

accordance with the Paduan (fig. 35c)[65],

whereas Strada turned the dolphin into a helmet and the turtle

into a globe (fig. 36a)[66].

The model for Strada’s

depiction can be found today in the Vienna Coin Cabinet (fig.

36b). It originally came from the Tiepolo Collection.

Senator Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo had acquired Sebastiano

Erizzo’s famous coin collection at the end of the seventeenth

century; in 1821 it was sold to Emperor Francis I of Austria[67].

Thorough examination of this piece showed that it was much

reworked – possibly even a cast[68]

– and in all likelihood not an original[69].

Therefore, the drawing was certainly modelled on the piece from

Erizzo’s collection, with whom Strada was closely associated, as

numerous owners’ details in the Diaskeué attest[70].

Unfortunately though, this coin is neither described nor

illustrated in Erizzo’s work Discorso sopra le medaglie[71].

The obvious diversity

between the description and illustration of this piece ought to

be seen as evidence that the Diaskeué does not contain

coin descriptions that complement the illustrations in the

MaNO. Originally, this assumption

had provided the foundation of our project and was based on

Strada’s statement in his book catalogue[72]

and on his declaration in the

preface to his commentary on Caesar[73],

in which he explained that the coin descriptions in the

Diaskeué were meant to match the drawings after ancient

coins in the MaNO.

This short summary shows

that Strada – although he was aware of the problematic issue of

modern creations after the antique – was not always able to

distinguish between originals and imitations. To tell them apart

would have required – in addition to a thorough autopsy and

related methods of examining the material, presentation and

legends – the use of an accepted reference work or catalogue.

Unfortunately, at the time, no such work existed. Extensive

research and a proper methodology of comparison, for which none

of the prerequisites were yet available, would have been

necessary. Strada’s Diaskeué was a first attempt to

compose such a work. Interestingly, it did not meet with the

expected success, since the Diaskeué was never printed

and only survived in two complete manuscript copies[74].

Thus the work was only known to specialists, such as Adolfo Occo

(1524‒1606)[75],

as well as to the imperial librarian in Vienna, Peter Lambeck

(1628‒1680), or Charles Patin (1633‒1693) whom Lambeck guided

through the imperial library[76].

Therefore, Strada never received the full ›scholarly‹

recognition for his work by his fellow antiquarians.

In addition, there was a

desire for completeness which was not only characteristic of

Strada, but also of the other so-called artists-antiquarians,

such as Enea Vico, Pirro Ligorio and Hubertus Goltzius, who were

led by this ambition to create reconstructions or imitations

(inventions/fantasies)[77].

Consequently, Strada stated the following reasons for this type

of invention in the preface to the first volume of the

SERIES Impp. Roman. ac Graecorum et

Germanorum omnium a.C. Iulio.C.F.C.N. Caesare usque ad

Maximilianvm II. Caes. P. F. Aug. una cum liberis patrimis atque

matrimis ex a.a.a. numismatibus quam fidelissime delineatis:

inservimus etiam iuxta tempora hexarchos et longobardor reges

omnusqve cum ipsorum elogiis breviter descripsimus. Tomus primus

continet XII Caes. a C.IVl.C.F.C.N. Caes. usq. ad Nervam Imp.

Ex Musaeo. Iacobi de Stradae Mantuani

Caess. Antiquarii Civis Romani[78]

– meant as a short synthesis of

the MaNO and the Diaskeué and intended as a gift

for rich patrons, in particular the emperor: »Nevertheless, in

any case it is true that not all coins match all inscriptions,

as I would prefer: the reason is that not all of them were

discovered, although all of them were minted«[79].

Due to their knowledge of the material and iconography, these

artists-antiquarians, i.e. the engravers Cavino, Cellini etc.,

were also able to create »inventions after the antique«. This

kind of creativity contradicted the intention of the so-called

›humanist antiquarians‹, such as Antonio Agustin and Jean Matal,

who wanted to explore antiquity in all its aspects entirely on

the secure basis of authentic ancient monuments and literary

sources[80].

Therefore, Agustín was suspicious of inventions by

artist-antiquarians, as he expressed in the well-known statement

in his work Dialoghi intorno alle medaglie, iscrittioni et

altri antichità:

My friend Pirro Ligorio

from Naples, a great antiquarian and painter, wrote over forty

books [i.e. manuscripts] about coins, buildings and other things

[...] without really mastering Latin, as did Hubertus Goltzius,

Enea Vico, Jacopo Strada and others. Those who read their books

might think that they read all the Latin and Greek books ever

written. They took what they needed from others and they exactly

drew with the pen what others described […][81].

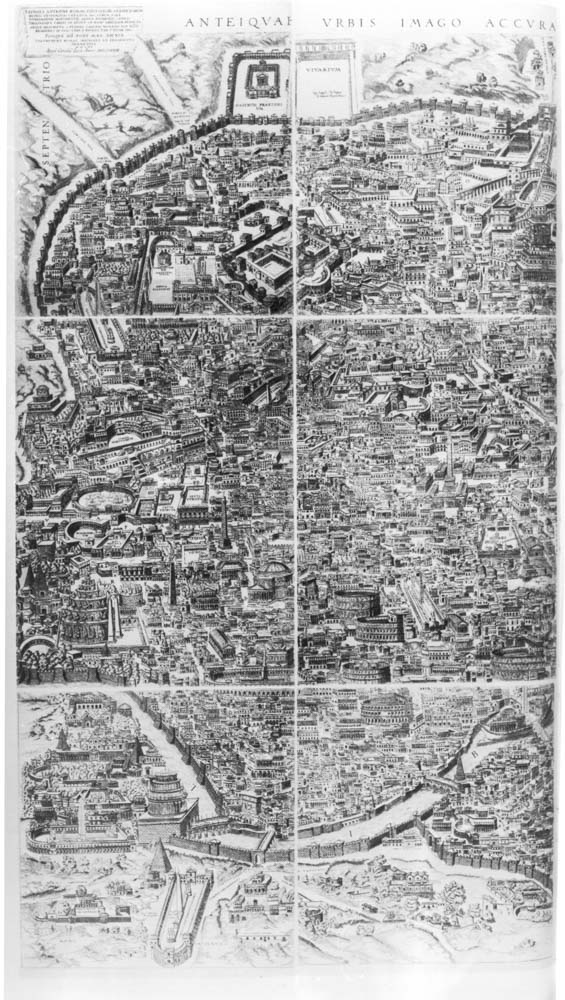

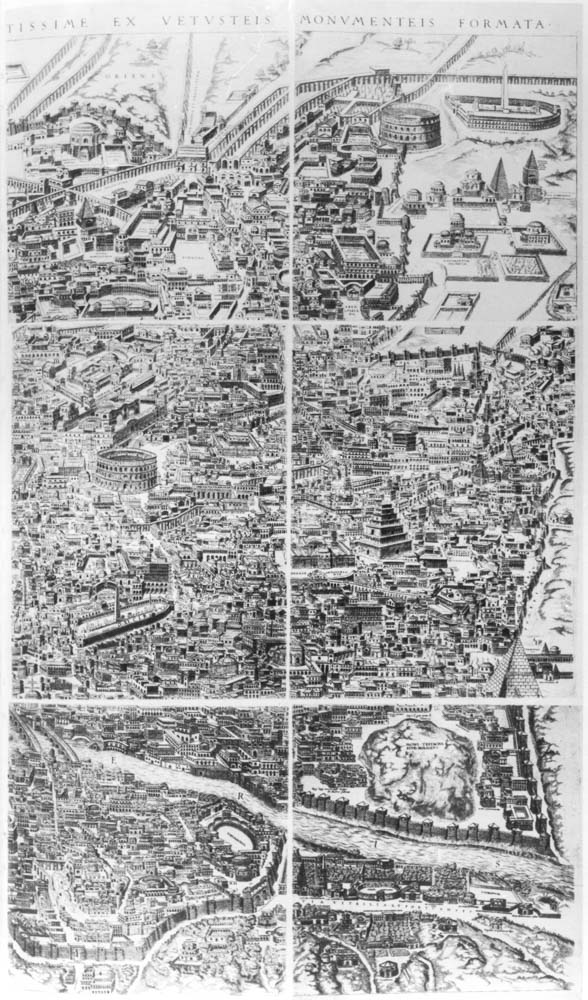

The artist-antiquarians

wanted to reconstruct the ancient world as it had been using

their imagination and coin images. This development would come

to its peak in 1561 with Pirro Ligorio’s great plan of Rome

(figs 37a and b) Anteiquae urbis imago accuratissime ex

veteribus monumenteis formata, the buildings in which are

exclusively based on coin images[82].

Paduans and other

all’antica medals remained extremely popular well into the

eighteenth century. Until the end of the Ancien Régime, these

coins presented outstanding objects for the knowledge,

appropriation and moral-educative role they possessed, even

though or precisely since they had no ancient origins. Although

they began to be criticized as copies by scholars by the end of

the sixteenth century, they would not be rejected as forgeries

until the nineteenth century[83].

Translation: Andrea M.

Gáldy:

agaldy@hotmail.com

* My contribution was originally to

be presented under the same title on 2 April 2020 at the

annual meeting of the Renaissance Society of America in

Philadelphia as part of the session »Renaissance

Numismatics, Medals and Exonumia« which had to be

cancelled due to the corona crisis.

[1] On

Strada’s date of birth, see Heenes 2010, pp. 296‒297,

note 4. Most recently and comprehensively, Jansen 2019,

p. 48 on Strada’s life and work.

[2] Jansen 2014, pp.

155–172; Jansen 2019, pp. 57–60.

[3] Weskie –

Frosien-Leinz 1987, p. 35 with note 53.

[4]

Jansen 2019, pp. 60‒61.

[5]

Translation: Excerpt from the treasure of antiquities,

i.e. the images of Roman emperors, eastern and western,

drawn as faithfully as possible from ancient coins. From

the museum of Jacopo da Strada, Mantuan Antiquarian.

[6]

Strada used the woodcuts of the emperors and their

relatives once more in the Fasti et triumphi;

Dekesel 1993, p. 33.

[7] Heenes 2003, p.

21; Peter 2016, p. 167.

[8] Lemburg-Ruppelt

2000, p. 115.

[9]

Ibid.; e.g. Epitome, pp.

13‒14:

temple of Janus Quadrifrons from

MaNO

4, fol. 237r;

p.

18: The

mausoleum of Augustus from

MaNO

5, fol 213r,

or pp.

62–63:

the Palatium Nervae from

MaNO

14, fol. 24r. However, no

genuine coins can be linked to the drawings mentioned.

[10]

Translation: Important and new work, containing

the description of the life, the images and of all coins

of both the Western and Eastern emperors and of the

tyrants (usurpers), with their co-regents, wives and

children, up to Emperor Charles V. Elaborated by Jacobo

de Strada from Mantua. First volume, 1550.

[12] E.g.

Epitome, p.

27: an

aureus of Claudius with the Aqua Claudia (really

the praetorian camp),

RIC I2 Claudius 7;

p.

56: a

sesterce of Titus with the Colosseum,

RIC II,12 Titus 185;

p.66:

a sesterce of Trajan with the Circus Maximus,

RIC II,2 Trajan 571/MIR

175a; pp.

102–103:

Ritus Ludorum Secularum Templum duobus colonis

insistens,

RIC IV Geta 132;

p.

111: a

contorniate of Elagabalus with

the Temple of Sol Invictus,

Gnecchi 1912, vol. 3 p. 40 no. 6; p.

114: a

denarius of Alexander Severus with the restored

Colosseum,

RIC IV Alexander Severus 33;

p.

129: a

contorniate of Philippus Arabus with an amphitheatre

(Colosseum), Gnecchi 1912, vol. 2 p. 99, no. 12; p.

134: a

sesterce of Vibius Trebonianus Gallus with the Temple of

Juno Martialis,

RIC IV Trebonianus Gallus 54.

[13] Lemburg-Ruppelt

2000, p. 115.

[14] Heenes 2003, p.

21. On Varro’s system, see

Momigliano 1950, p. 289.

[15] On

the difference between the terms ›imitations‹ and

›fantasies‹, see de Callataÿ 2014, pp. 269–291.

[18]

Missere 2013, p. 280.

[19] Out

of 3,764 drawings from the first 14 MaNO volumes,

examined up to now, about two thirds could be matched

with ancient models. About 18 Paduans have so far been

identified.

[20]

MaNO

2, fols 3r‒4r.

[21]

Translation: Description of ancient gold, silver and

bronze coins, i.e. explanation of the coin images of the

Chaldeans, Arabs, Libyans, Greeks, Etruscans and

Macedonians, Asians, Syrians, Egyptians, Sicilians,

Latin and Roman kings from the foundation of the city,

of the gods, the consuls at the time of the Roman

Republic until today, both among the Latin emperors in

the West and among the Greek emperors in the East and

finally, when the empire of the Roman people perished,

of the exarchs and of the princes and dukes of the

barbarians. From the museum of the Mantuan antiquarian

Jacopo Strada, Roman citizen. With seven very reliable

indices, partly alphabetical, which contain the most

diverse things, partly chronological, which describe the

names of the kings, caesars, emperors and tyrants and

also of heroes.

[22]

On the description of the reverse,

see Diaskeué 2, fol. 123v, p. 72 no. 3.

[24] Here

and on the following, see Lemburg-Ruppelt 2000, p. 117

with note 13.

[25] Livy,

Ab urbe condita liber CXX periocha.

[27]

Information by Massimo Bulgarelli, Venice.

[28]

Information by Ingo Herklotz, Marburg, and Arnold

Nesselrath, Rome.

[29]

Information by Ingo Herklotz, Marburg; Cichorius-scenes

XXIII und LXXI.

[30] ÖNB

shelfmark Cod. 9410; Jansen 2019, pp. 684‒685; p. 860.

[31]

Information by Arnold Nesselrath, Rome, and Timo

Strauch, Census, Berlin.

[32]

MaNO 3, fols 178r–179r.

[33] Information by

Karsten Dahmen, Münzkabinett SMB, Berlin, and Michael

Matzke, HMB, Basel.

[34]

Plutarch, Antonius 68,1.

[35]

Discours, p. 20; RIC II Hadrian 62 (=

RIC II,32 Hadrian 509-510);

RIC II Hadrian 662 (RIC

II,32 Hadrian 748).

[36]

MaNO

9, fol. 145r. (CensusID

10183804,

RIC Nero 323)

[37]

Information by Michael Matzke, HMB, Basel.

[38] The

previous

folio 236r in MaNO vol. 4

depicts the uncrowned Augustus accompanied by a divus

legend.

[39]

Discours, p. 21.

[40] Ohm

2014, pp. 81‒83; Ohm 2015, p. 221; Darnis 2003, pp.

15‒17; Stahl 2015, pp. 266‒287.

[41]

Zeitz – Zeitz 2003, p. 140 no. 63.

[42]

Zeitz – Zeitz 2003, p. 187 no. 98.

[43]

MaNO 1, fols 233r‒234r.

[44]

Diaskeué

2, fol. 88r, p. 1 Nr. 2;

not illustrated in the Dialogos.

[45]

Agustín bequeathed his coin collection to the Spanish

king. It included 130 gold coins, 1400 coins in silver

and 3871 in bronze. The bronze coins were taken to the

coin cabinet at the monastery San Lorenzo de El

Escorial. They were stolen by Napoleon’s troops; their

present location is unknown. In the original edition (Dialogos)

only 292 coins are depicted on 52 pls. These coins

probably came from Agustín’s collection (information

provided by Paloma Otero, Museo Arqueológico Nacional,

Madrid and Mariano Carbonell, Universitat Autònoma de

Barcelona).

[46]

Klawans 1977, p. 21 no. 5: Obverse: Caesar laureate

l.r., DIVI IVLI; Reverse: Caesar riding the elephant

quadriga, LS SC. Most recently: Asolati 2018, pp.

138–139. A potential model for Cavino could have been an

Egyptian bronze coin of Trajan (RPC

III, 4667, 2). Information

provided by U. Peter, BBAW, Berlin.

[48]

Klawans 1977, p. 68 no. 7.

[50]

Diaskeué 3, fol. 118r no. 4 (CensusID

10193997)

with MaNO 11, fol. 128r–129r

(CensusID

10193992

and

10193995);

Klawans 1977, p. 64 no. 6, Colosseum with Meta Sudans.

[51] RIC

II,12 Vespasian 194 (CensusID

10051539);

RIC II,12 Domitian 131 (CensusID

10066886).

Matzke 2018, pp. 144‒145; p. 149.

[52] See

Matzke 2018, p. 148 no. I.51. Whether the left-facing

Vespasian and the legend COS VIII is an independent

type, so far unknown to scholars, or whether Strada made

mistakes here, must remain open.

[53]

MaNO 9, fol. 30r and fol. 31r; RIC I2

Nero 179; Klawans 1977, p. 44 no. 2 (CensusID

10183794

and

10183797).

[57]

Klawans 1977, p. 24 no. 5.

[58]

Alföldi 1976, p. 225.

[60] RIC

II,12 Vitellius 113.

[62] The

sesterce of Vitellus with Honos and Virtus illustrated

therein (Dialogos, p.

94; RIC

I2 Vitellius 113, CensusID

10187200)

matches Strada’s description in der Diaskeué, as

well as the illustration in the Italian edition of 1592

(Discorsi, pl.

9). In

the second Italian edition of 1592 (Dialoghi, p.

81) the

illustrations are embedded in the text and the

illustration matches Cavino’s copy.

[63] AST

21, p. 183, fol. 134v.

[64]

Klawans 1977, p. 58, no. 1; Matzke 2018, p. 143 no.

I.47.

[66]

MaNO 10, fol. 232r (CensusID

10187213).

I would like to thank Jonathan Kagan, New York, for

bringing this discrepancy to my attention.

[67] Asolati

– Cattaneo 2019, pp. 133‒134 no. 69 (Marco Callegari).

[68]

Information by Michael Matzke, HMB, Basel.

[69] Information by

Klaus Vondrovec, KHM, Wien.

[70] See,

for example, Diaskeué 2, fol. 166v, p. 159, no.

108; fol. 182v, p. 192, no. 17; Diaskeué 3, fol.

220r, p. 626, no. 5; fol. 220v, p. 627, no. 7;

Diaskeué 4, fol. 77v, p. 792, no. 6;

fol. 105r, p. 847, no. 11.

[71]

Discorso; the coin is not even included in the later

editions of 1568, 1571 and 1585-1590.

[72]

Index sive catalogus librorum; ÖNB Cod. 10101 fol.

1v: Alius liber de omnis generis ethnicis et antiquis

numismatibus aureis, argenteis et aereis, quae passim in

universo mundo inveniuntur, et ego magnis impensis et

cura acquisivi, quae latine in XI voluminibus descripta

sunt. Et hac numismata partim ipsemet et apud me habeo,

sicuti fabrefacta et excusa sunt; partim ipsemet manu

mea delineavi ex ipsis numismatibus veris passim

estantibus apud antiquitatum studiosos et viros

primarios. Suntque eorum quae descripta sunt novies

mille; et inter haec multa peregrina, utpote latina,

graeca, hetrusca, arabica et aphricana variis

characteribus et literis insignita, prius apud nos non

visa et conspecta.

[73]

C. Iulii Caesaris,

Dedicatoria: Missus sum ab hinc annis

20. in Italiam, Romam, Venetias ac alio ad numismata

auro, argento, ac aere efformata, vetustateque insignia

marmora comparanda, quae ego magna vi pecuniarum expensa

Augustam, nobilissimis spolijs exuta Italia, advexi.

Sunt inter ea quam plurima Imperatorum ac Imperatricum

capita, multae insuper integrae marmoreae statuea,

aliaque opera non minimi precij & pervetusta. Haec omnia

quoque familiae Bavariae cesserunt. Verum nec illud

silentio involuere possum, apud eundem Fuccarum

absoluisse me mea ipsius manu 18. magna volumina

numismatibus referta studiose delineatis ex archetypis

suis aureis, argenteis ac aereis, in quorum sunt & ea

numero quaecunque ego numismata uspiam terrarum totos

hos annos 30. quos in hoc studium absumpsi, videre

potui. Additae sunt autem singulis descriptiones Latinae

non suppressis etaim dominorum suorum, apud quos mihi ea

videre contigit, nominibus. Haec omnia coniecta in 11.

magna volumina cum alijs meis maximis ac dictu

incredibilibus laboribus Fuggerus suae Bibliothecae

addiderat.

[74]

University Library Vienna, shelf

marks Ms III, 483 and

Hs III 160898/1-11;

Czech National Library Prague, shelfmarks Codd

1197–1207.

[75]

The structure of Adolfo Occo’s work Imperatorum

Romanorum is strongly reminiscent of the systematic

subdivision adopted by Strada in the Diaskeué;

information provided by Jonathan Kagan (New

York). For this work, see the PhD thesis of Gruber 2006,

pp. 5‒7.

[76]

Jansen 2019, pp. 10–13.

[77]

Further details: Missere 2013, pp. 279–281.

[78]

Translation: Series of all emperors of the Romans,

Greeks and Germans from Gaius Julius Caesar, son of

Gaius and grandson of Gaius, up to Maximilian II,

Caesar, the pious and happy Augustus, together with the

children, whose father and mother are still alive, from

bronze, silver and gold coins: We have also classified

all the exarchs and kings of the Lombards in accordance

with the times. We have briefly described these together

with their own inscriptions. The first volume contains

the twelve Caesars from Gaius Julius, son of Gaius and

grandson of Gaius, to Emperor Nerva. From the museum of

the Mantuan Jacopo Strada, antiquarian of the emperor

and Roman citizen (CensusID

10082563).

[80] See

the detailed discussion in Heuser 2003, pp. 88‒103.

[81]

Dialoghi p. 117.

[82] Most

recently: Long 2018, pp. 137‒138.

[83]

Burkart 2018, p. 25.

In his

letter of 29 January 1695

to Nicolas Thoinard (1629–1706), Andreas Morell

(1646–1703) criticized Strada’s imitations. The invented

coin of Vespasian, mentioned in the letter, is included

in MaNO 11, fols

22r–23r.

Information provided by F. de Callataÿ, KBR, Brussels.