Looking Beyond: Stories & Perspectives

European Borders: Hostile Terrains in the Aegean/Mediterranean Sea

Drawing on the notion of statecraft as “the construction of what it means to be a subject of politics through a variety of practices that sustain certain conceptualizations of the state”, political science professor Jessica Auchter emphasizes the myriad ways in which statecraft is enacted and focuses on the construction of politically qualified subjects of the state or ‘citizens’ and those beyond the limits of qualified politics or ‘ungrievable lives’, referring to Judith Butler[1]. The role the border plays in the subject production gains importance here as it implies a shared sense of past within that bordered territory while creating the division of “us” and “them”, and thus inventing ‘the other’ whose life would be ungrievable and unmemorialisable because memorizing ‘the other’ would question the fixity of the border as well as the founding myth of the state that depends on this separation between “us” and “them”[2].

Hence, memorialization embodies the potential of resistance to the mechanisms of statecraft, yet in the case of the Hostile Terrain 94 exhibition where in some cases there is not even any identity or any detailed information about the deceased people, this anonymity itself becomes the act of remembrance. The status of these people beyond the border, their being anonymous and unidentified are what is remembered in this project. Moreover, it also aims to grieve every lost life “without regard for classifying a life a grievable life”[3]. Cultural critic Andreas Huyssen emphasizes the fear of forgetting prevailing in the world as a result of the dynamic aspect of the media that provides disposable data[4]. In our contemporary world, where we read about immigrants dying while crossing the border, feel compassion for them and move on to read other news, we constantly face our incapability of doing something regarding these atrocities which are, only in some cases, reported, read, empathized and forgotten. Just take a minute and think about the high media coverage about the refugees in Moria on the Greek Island Lesbos after the camp burnt down. But now? Have those who are especially in need of protection (for example children) been really taken to a safer place in Europe like it was promised by politicians? When was the last time you heard about it in media?

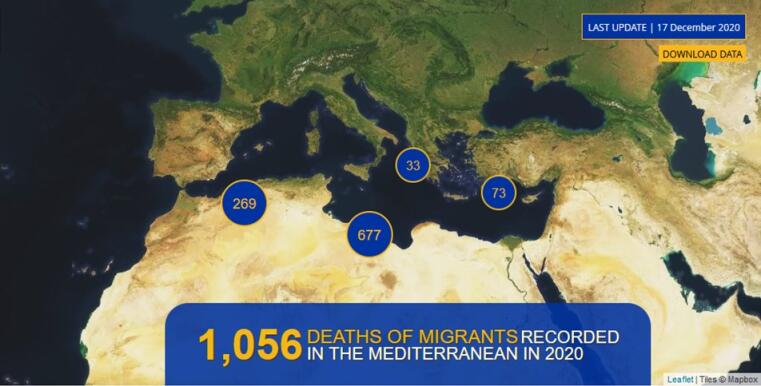

An exhibition project like this that draws on the forgetting of the “unknown” about whom we often read in the news provides us with a perspective through which we can think about this subject production and destruction that relate to the notion of border and border patrol. It also encourages us to consider other atrocities around the world happening at the borders, which demonstrates common patterns regarding these notions. Within this context, it was inevitable to compare the border crossings in the Aegean Sea[5], which borders and separates the EU from the Middle East and has become another death trap for war-driven immigrants especially from Afghanistan, Syria and various African states, to the ones in the Sonoran Desert. They both present similarities along with sharp contrasts in terms of the challenges immigrants face during this life-threatening passage.

As you can see in the toe-tags, many of the causes of deaths in the desert are dehydration and hypothermia due to lack of water, scorching heat and perishingly cold nights of the desert, while in the Aegean Sea people die drowning in the perishingly cold waters while trying to cross it at night in order not to be seen. Setting these two contexts in parallel with each other is the aim of our Münster exhibition of the Hostile Terrain 94 art installation in order to create a solidarity between people in both continents who stand against the statecraft mechanisms, which marginalize people aspiring for better lives or, at its simplest, a life itself, and amnesia due to the dynamic media and hectic lives.

However, while the HT94 project focuses on the anonymity or unidentified dead immigrants, we chose to complement it by introducing the narratives of people who did manage to cross the border and how they gained their identities after surviving the Aegean Sea of forgetfulness and oblivion[6]. For this reason, we present the interviews of these people who share their experiences of crossing, surviving, building lives in a new land, adapting to a new society and culture while in some ways living in the liminality between here and there. We would like to remind you of the dichotomy of and the thin line between life and death, which is the two sides of this Janus-faced passage that people go through at the borders around the world.

[1] Auchter, Jessica. “Border Monuments: Memory, Counter-Memory, and (B)ordering Practices Along The US-Mexico Border.” Review of International Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, 2013, pp. 291-311.

[2] Auchter 295-299.

[3] Auchter 307.

[4] Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford University Press, 2003, pp.16-18.

[5] https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/10021/a-chronology-of-the-refugee-crisis-in-europe-1

[6] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lethe